Why Cambridge debates matter

Johana Trejtnar explores how Cambridge voices travel far beyond the UK’s borders

Earlier this month, Czech artist David Černý – invited to speak at the Cambridge Union’s final Easter term debate – appeared on national Czech television, launching into a dehumanising rant aimed at trans people. He warned of a dystopia in which individuals with “three sets of breasts” and “different genitalia on each shoulder” abuse social welfare systems and public toilets.

This show, which tens of thousands of Czechs tune into every weekend, brings together experts and well-known figures to discuss the week’s “hottest topics”. Recently, the show’s guests discussed the UK Supreme Court’s decision that the legal definition of a woman is based on biological sex.

Not a single trans woman was invited to the Czech TV debate. Instead, it gave Cerny, known for his “anti-woke” rhetoric and sculptures showing heavily objectified female bodies, a platform and free range to publically dehumanise trans people.

“The UK influences people all over the world while seldom adopting foreign culture”

The rhetoric mirrored a broader trend: the replication of Anglo-American “anti-woke” discourse in Czech political culture. But this permeation is not isolated to trans rights. The influence of UK and US media, politics, and cultural discourse is disproportionately strong in the Czech Republic. British debates routinely shape Czech public opinion. The reverse? Not so much.

This asymmetry is no accident. By becoming the world’s largest empire, amassing enormous amounts of wealth, and instilling its language as the world’s lingua franca, the UK gained immense ideational power. As a result, the UK influences what people all over the world learn, watch, and read, while seldom adopting foreign culture into its own discourse. But people in the UK often seem to remain blissfully ignorant to this unequal equation.

Recently I was listening to a journalist refer to Queen Elizabeth’s death as an event of enormous world consequence. He said that, no matter who they are, everyone remembers where they were when they found out that the queen died. His statement struck me as absurd. Why would the British queen’s death be relevant to my life, as someone who grew up in a country whose only real tie to the UK was severed by Brexit? And yet I remember exactly where I was when I heard the news: sitting in literature class.

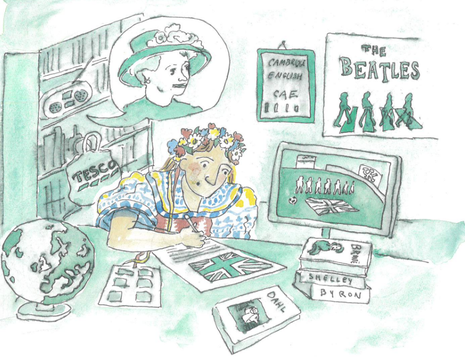

In the Czech Republic, we learn English, memorise the UK’s tallest mountain, learn about Harald Hardrada, watch Wallace and Gromit, read the Brontës, follow UK football, watch the Great British Bake Off and listen to the Beatles.

“Whether we like it or not, what happens in the UK – and what happens at Cambridge – ripples far beyond its borders”

Meanwhile, in the UK, I’ve been asked if we speak German in the Czech Republic (we don’t) or whether Czechoslovakia still exists (it hasn’t since 1993). A Cambridge history supervisor supposedly once mused about whether the Prague Spring happened in Poland. And if this is true of a EU nation never colonised by the United Kingdom, the questions students from non-Western countries receive must be ten times worse.

This isn’t just ignorance – it’s a tangible reflection of whose narratives dominate. And at institutions like Cambridge, that influence is amplified.

Last week I opened a magazine in Prague and, in a list of the five major world news stories, two mentioned elite Anglo-American Universities: Harvard and Cambridge. While people care what happens in the UK, they care tenfold what happens at Cambridge. Otherwise Cambridge news would never make international headlines. When Cambridge speaks, the world listens.

That means small protests here get international media attention, while marches of a million in Serbia or airstrikes in Gaza are pushed aside. Whether we like it or not, what happens in the UK – and what happens at Cambridge – ripples far beyond its borders.

UK rhetoric has power - to inspire people, who read about Cambridge discoveries on extraterrestrial life, but also to embolden figures like David Černý.

While this influence should be questioned – for its imperial origins if nothing else – it is nevertheless strongly tangible on the ground. Not paying attention to the world consequences of things that happen here can lead to an underestimation of the weight of the choices made on British ground.

If you are at Cambridge, your voice is amplified. Your political decisions matter, your public debate matters, your activism matters - on a much larger scale than you may realise.

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026

News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026 News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026

News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026 News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026

News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026