The Lolita complex

Beatrice Tharme examines the influence of Nabokov’s novel, and the endurance of child sex abuse in the Arts

Trigger Warning: this article contains discussion of child sex abuse

Humbert Humbert is the ultimate unreliable narrator. However obvious Vladimir Nabokov makes this, popular portrayals of the teenage girl, Lolita, have been overwhelmingly unsympathetic. Now, we are submerged in a political milieu characterized by culture war. Political correctness makes a re-envisioning of the villainised Lolita unthinkable to us, at least in the way that films of both the ’90s and ’60s imagined her. Little known to pop culture is Lolita’s real name, Dolores Haze – her perspective is always enshrouded by Humbert and mystifying to the viewer. Whether portrayed as a teenage seductress, precocious and intelligent young woman, or tragic and vulnerable prey for Humbert to take advantage of, Lolita’s experience has been consistently romanticised. Early criticism for Nabokov’s novel called Lolita a “love story” – something it decidedly isn’t, no matter how you view its tragic heroine. I suggest that the countless imaginings of this teenage heroine, whether in music, film or novel form, perpetuated the sexualization of young girls. Directors and predatory male viewers have used Lolita to excuse their perversions; nymphet culture is not as ’60s as we may initially think. However, some depictions do focus on the Dolores beneath the rose-tinted glasses – this is a duality worth discussing.

“Directors and predatory male viewers have used Lolita to excuse their perversions; nymphet culture is not as ’60s as we may initially think”

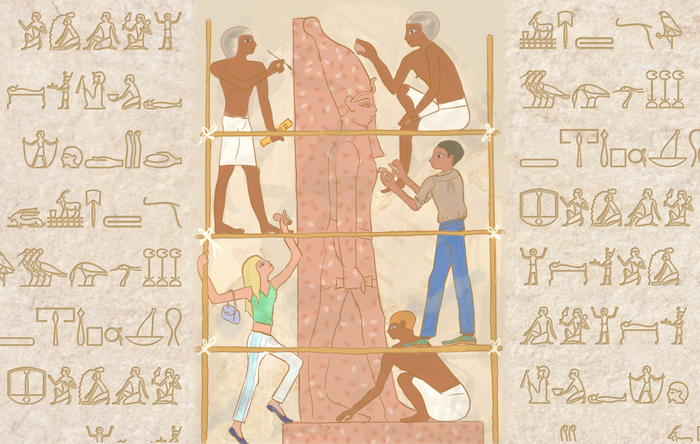

Lolita is far from the first tale of child sexual abuse that has garnered such appraisal in the literary canon. We could dial it back to the classics: Persephone has just come of age (gotten her period at presumably 12 or 13 years old) and is already being preyed on by Hades, a much older man, who is also her uncle. He tempts her with pomegranate seeds, steals her away from her distraught mother Demeter, and marries her. Humbert Humbert displays such cunningness as Hades, willing to marry Dolores’s mother in order to get closer to her 12-year-old daughter. Nabokov’s novel, despite the unreliability of Humbert’s accounts, deliberately allows Dolores’s fear and discomfort to seep through the cracks. Nabokov, a survivor of child abuse himself, makes this version of Dolores available to the attentive reader. So, why do so many accounts of the story, whether it be in film or on stage, refuse to give the titular character any agency?

Stating the obvious, that these films are created by male producers and big-time Hollywood executives for the male gaze, is not an original angle to take. It also affords far more sympathy than a child sex abuser like Humbert deserves. Not to mention that many of these producers, like James B Harris of the 1962 version, are rumoured to have sexually abused the young girls that played Lolita. These films are heavily responsible for the sexualization of these young actresses, damaging their mental health, careers and exposing them to experiences beyond their years. This attitude continued far later than these adaptations; teenage actresses like Emma Watson and Natalie Portman had to cultivate ‘bookish’ images to feel safe in their own bodies. Portman’s 18th birthday was shadowed by a countdown at her local radio station and Watson was ambushed by paparazzi and up-skirted by photographers. The day after MeToo headlines hit the newspapers, the front page questioned the relationship status of teenage Millie Bobby Brown. The Lolita-complex strikes again and again.

“Aesthetic fascinations with Lolita have claimed to be empowering, but this is only possible when detached from the abuse”

This novel that focuses on the fictional character of Humbert’s own making, Lolita, instead of the frightened Dolores has spawned fascinations in music, such as Lana Del Ray’s repeated references to Lolita or Lolita-inspired dynamics. Movies like The Crush, starring Alicia Silverstone as a teenage seductress, and Drew Barrymore in The Amy Fisher Story developed the romanticized ’90s perspective of Lolitas. Pervading images and symbols, such as the young 1997 Dominique Swain staring over her red heart-shaped sunglasses, have contributed to misconceptions about the character of Lolita; she becomes an impassioned teen pursuing an adult rather than the abused, forgotten Dolores of Nabokov’s book.

There are very few depictions of Lolita that are progressive, although many conversations about the original book and seminal film adaptations are happening now and consider the wider context of the topic at hand. Reading a novel like My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell captures the influence that the Lolita-complex has had, especially as the novel by Nabokov is used in Russell’s work to romanticise the inappropriate relationship and abuse between Vanessa and her male teacher. The narrative flicks between her school days, amid the abuse, and a post-MeToo Vanessa, attempting to contend with her experience, still not quite feeling like a victim despite clearly being impacted and traumatised by her teacher’s pursuit of her younger self.

So, why is Lolita such a fascination? Why is pop culture so hung up on it as a source of inspiration? Precociousness is often perceived as seductive naïvete, yet it is a mode of being that should not be desirable but powerful. Aesthetic fascinations with Lolita have claimed to be empowering, but this is only possible when detached from the abuse that leaves Lolita in her desperate state at the end of the novel. Even the heart-shaped sunglasses of Taylor Swift’s Red could be an easter egg alluding to Lolita. We see references to Lolita everywhere in pop culture; it is most important to notice which aspect of the novel (and which version of Dolores, Lolita, or Lo) is being reimagined. No matter how Humbert disguises his mistreatment of Dolores as poetically romantic, reciprocated love, his echoing of Edgar Allen Poe and other poets that idealised and sexualised young girls remains troubling. Humbert is of course wrong in his insistence that poets cannot be killers. They may just be better at hiding their abuse.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026