Our big, fat annotation addiction

Niall Quinn argues that physical annotation is here to stay

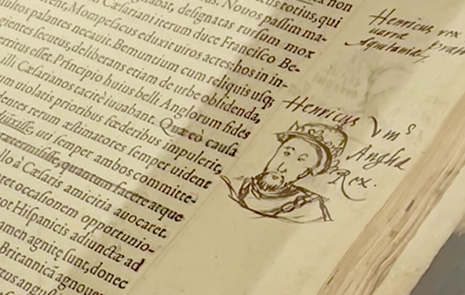

In the Old Library of Queens’ College, there exists the bequeathed library of Sir Thomas Smith, a sixteenth-century English humanist, diplomat, and Queens’ alumnus. In addition to providing an intriguing insight into various aspects of Tudor intellectual life, it also evidence Smith’s ineradicable lust for annotation. While it is commonplace to find marginalia of some kind in sixteenth century books, Smith’s are in another realm of complexity: whenever he encountered a name or place with which he was familiar, he churned out an illustration of that person or place in the margin. On the page of Paolo Emili’s De rebus gestis Francorum (1550) photographed above, for instance, Smith scribbled out an illustration of a city and a rather dashing likeness of Henry VIII (whom he knew personally) – chin strap and all. These two examples demonstrate that, for him, annotation was a means of tethering the foreign words of another author directly to his own life – and putting his stamp on otherwise unremarkable bits of paper. Strikingly, hundreds and hundreds of these detailed annotations exist throughout almost all of his many surviving books. We could say, therefore, that it was a kind of Tudor legal high.

But does it still provide the same buzz in the 21st century, and in Cambridge in particular? With college cocktails, formal wine, and – crucially – Notion firmly in the arena, has annotation addiction been relegated to the confines of bibliophilia circles? The answer is, of course, entirely dependent on whom you ask. A quick TikTok search will provide you with plenty of evidence that A-level English Literature students either worship or scold annotation: comments like “it’s just so satisfying: I’m never going back” and “uuhhhhh, books aren’t meant to be canvases” sit almost gracefully next to each other. Personally, I derive my instant gratification from other sources: my utterly illegible handwriting (thanks, dyspraxia) has forced me to become wedded to Google Docs. But that doesn’t mean that I avoid annotation at all costs, nor does it mean that it isn’t something Cambridge students make merry with today: even I occasionally find myself scribbling on term cards and bi-weekly Varsity newspaper editions. Indeed, it is a testament to its potency that, even with a free Microsoft Office subscription being offered by the University, those students annotating by hand – in my experience – outnumber those embracing the digital age.

“We could say, therefore, that it was a kind of Tudor legal high”

Moreover, visit one – just one – Sidge library and you’ll inevitably understand what I’m talking about. Take any book which hasn’t been published in, say, the last five years from a shelf. Annotations, impassioned or otherwise, will abound. Whether it be underlining whose copiousness defeats the entire purpose of underlining or comments like “Use p. 145 and p. 176 for lead para. I so got this” (an actual quote inside a copy of Christopher Haigh’s English Reformations I found in the Seeley once), the defacing of faculty and college property demonstrates that someone is still getting a kick out of this. Their antics not only mentally rejuvenate them, but provide some entertainment for the more deferential among us. In fact, I’ve found that stumbling across randomly placed exclamation marks and comments “This is an ITALIAN concept!!!!!!!!” (a quote from the Seeley copy of Glenn Richardson’s Renaissance Monarchy) acts as a soothing agent during a particularly keyboard destruction-inducing essay sesh: perhaps it’s a sense of reassurance that someone, somewhere, at some point was as irritated as (if not more than) I am.

“I’ve found that stumbling across randomly placed exclamation marks and comments acts as a soothing agent during a particularly keyboard destruction-inducing essay sesh”

But who, you might be wondering, is responsible for all this defacement? One insidious mastermind determined to bring down the University’s pristine bibliographical reputation? A team working under the auspices of some illicit secret society? We’ll likely never know. However, by dint of great fortune, I managed to make contact with one self-styled ‘Sidge scribbler,’ a friend of a friend of a friend and second-year Engling who wished to remain anonymous. They told me that they’ve been “intentionally leaving [their] mark on books only occasionally since Lent 2024, typically when [they] find something funny.” These quips, they tell me, are often ’with reference to modern humour, for instance, [sic] [they] just wrote “Bro is not that guy”next to a page in Act 4, Scene 2 of The Two Gentlemen in Verona, in which Proteus is rejected by Silvia. Upon enquiring as to whether they think this practice is ethical, given that it might in some cases damage books, they tersely responded “There are worse things to be concerned about.” While I do not condone this kind of scribbling, it is clear that the same buzz that so enraptured Smith all those years ago is still alive and well.

Physical annotation, then, still exercises a great deal of influence over us, regardless of how dominant Notion, OneNote or Google Docs are in the academic world. It, for example, enables you to capture your thoughts on a given matter immediately, thereby allowing you to remember both the content and your interpretation of it better. For others, like the Sidge scribbler, it’s just a means of making one’s mark and indulging in some transgression. But above all, it allows us to establish a tangible dynamic with the page, making reading not so much a lecture, but a multi-way dialogue. Even if it is just an amusing drawing of Boris Johnson, quite literally take a leaf out of Smith’s book and scribble!

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026