Review: The Mays 33

Heather Leigh explores the poetic worlds within the recently published student anthology The Mays 33

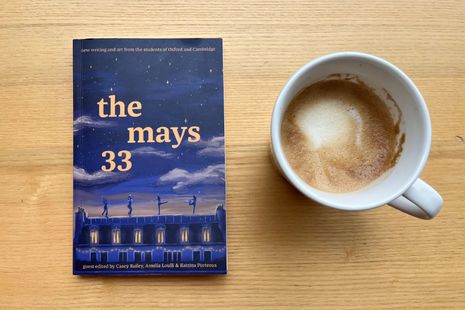

My first impression of The Mays 33 is of something small yet substantial, dark yet light. Holding the book in my hands, I am struck by the way the deep purples and blues of the front cover are pierced through by stars and lit windows, offerings of light which are at once cosmic and domestic. Yet the brightest thing on the page is the words themselves, a shining beacon to the wandering eye. The words which fill the inside of the book are equally as luminous. In ‘Sunscraps, from Early Days’, Ahana Banerji realises that “the light would continue, / regardless of how we slanted our blinds […] the sun would continue to burn / and I would be there to feel it.” Light is an unstoppable force, but that is not to say it doesn’t falter.

These are poems of darkness too, ranging from intimately personal losses (as in Enya Crowley’s ‘Funeral’) to a global sense of loss in the face of conflict and destruction (as in Lauren Lisk’s ‘It’s Six O’Clock and I’m Watching BBC News’). Lisk describes her TV offering “a one-boxed one-framed version / of real life”, but in doing so she creates more frames through which to see the world, frames in which the act of catching water while “washing my hands at the sink” becomes “like hands cupping blood from a wound”.

“The brightest thing on the page is the words themselves, a shining beacon to the wandering eye”

Multiple versions of multiple realities fill The Mays: it is an anthology of varied landscapes, despite unifying themes of bereavement and a craving for connection. You’ll find marigolds and ginger cats amidst the rubble of blown-up and bombed-down buildings, you’ll hear the scallop from which Venus emerged speak of this ‘Kardashian’ of Roman mythology, you’ll witness photos and illustrations as evocative and ambiguous as the words which surround them. A personal favourite is Daisy Cooper’s ‘My Garden is a Jungle’, with vivid colours and blurred edges evoking both the vibrancy and ungraspability of life.

“The poem is as juicy and slippery as the fruit which provides its title, offering the reader its own kind of sustenance, mouthfuls of language which recall a sweeter time”

Rephrasing Chaucer, Philip Kerr writes of “a rowdy parliament of things”, allowing ancient voices to resurrect and resonate with modern references, deft puns and verse which is swift but disjointed, like the frenzied flight-line of some winged creature. Pears become birds who in turn become speaking beings at an “interspecies symposium”. From the misheard and mistranslated conversations which fill Edward Rous’ ‘Three Studies’, to the heartbreakingly unclarified truths of Esther Forey-Miller’s ‘Churchill Hospital’, the voice is both the site of connection and the blockade against it.

The possibility and impossibility of speech is a recurring concern: Martha Vine ventriloquises the mythical Lady of the Lake in ‘Merlin’s Girl’ but refuses to name her; in ‘Oh-Double-Seven’, Madeleine Browne memorises her mother’s phone number by heart, in the hope that “I could phone her / wherever she will be / and ask her how to poach an egg”; Laura Zhang’s ‘On Lychee’ remembers sharing fruit with her grandmother, with “mouths / full, as if to speak”. The poem is as juicy and slippery as the fruit which provides its title, offering the reader its own kind of sustenance, mouthfuls of language which recall a sweeter time. Ripe with longing and loss, these words burst open on the tongue. I first opened The Mays lying in the long grass of Grantchester Meadows, eating strawberries and watching the river slide beneath the trees. I suggest you do something similar. Pack this book as part of a picnic. Unpeel the pages. Savour the taste.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026