Pinboards and quodilbets: a love story

Mia Apfel considers how early modern quodlibets might shed light on the ways we use modern pinboards

A pinboard often takes pride of place in the soulless box of a university student’s room. On this can be found an eclectic exhibition of postcards and photos, knick-knacks and found treasures, which might provide an alcove for fashioning identity and expression. Despite its limited size, the blank canvas of the pinboard offers unlimited opportunity for personalisation: a small-scale showcase of the self.

But for whom is the pinboard created? Is the pinboard a space of intimacy, used to foster domestic familiarity for its creator, or a surface upon which the creator’s identity might be exposed to others? After all, the displayed items are largely there to be observed and unpicked by outsiders entering the private space of the bedroom.

This pull between the two poles of creative intention, demanding the pinboard to be both a public and private form, is a familiar one. A dive into the forgotten art of ‘quodlibet’ paintings reveals the pinboard style to possess a longstanding history. The act of collecting and displaying items, from a print from the latest Tate Modern exhibition to a polaroid of friends back home, seems a modernisation or revival of this art form popularised in the 17th and 18th century.

The fashioning of pinboard-style paintings during the early modern period saw a surge in interest, attracting curiosity with their exposure of the intimacies and peculiarities of the domestic space. Quodlibets, a hyper-realistic style of art which depicted a cluster of everyday objects haphazardly pinned to a surface, made use of the popular trompe-l’œil (French for ‘deceive the eye’) technique of skilful verisimilitude. Reality is replicated through art: the boundaries between painting and life are blurred. Through the illusionary tricks of the paintbrush, the viewer is made to feel as if they are observing an actual pinboard whose objects are tangible, rather than a playful imitation of one.

“Through the illusionary tricks of the paintbrush, the viewer is made to feel as if they are observing an actual pinboard”

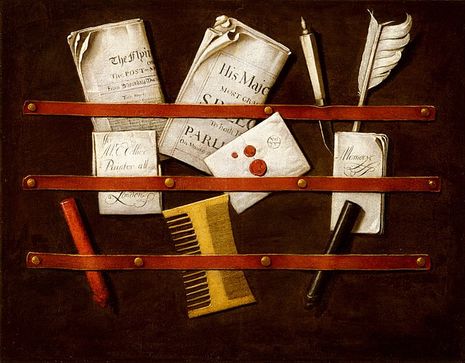

Evert Collier, a Dutch still-life painter, is one such illusionist. His quodlibets show a masterful hand, able to transform a flat surface into a three-dimensional space. His series of trompe-l’œils concentrate on writing materials and the commonplace practices of correspondence, depicting wooden boards upon which pens and quills, letters and stamps, are pinned. The microscopic precision of Collier’s paintings is entirely startling. The shadows behind a dog-eared letter, the texture of a feather down to its every plume, the timber circles of the pine board – they are almost indulgent in their commitment to small-scale detail: a flaunting of the artist’s ability to wield his brush in the process of creation. If the quodlibet is to be considered a self-portrait, exposing the artist’s own persona, then the very technicality of the painting, and the skill required to produce it, might be seen as another morsel of identity which the viewer is being encouraged to consume.

Nevertheless, perhaps these quodlibets are not simply studies of the self. The conflict between public and private that alters our perception of modern-day pinboards similarly shapes our interpretation of these illusionary paintings. Domesticity, taking its form in the personal possessions of a tortoiseshell hair-comb, a pocket-watch, or portrait miniature, exists in the same miscellanea as items of political significance. Translate the Latin quodlibet (‘whatever one wishes’ or ‘whatever it pleases’) and you will recognise this theme of encouraged randomness, still familiar to our contemporary perception of the pinboard as a fanciful amalgamation of oddities.

“The quodlibet’s personal-yet-private spontaneity and its being a nexus of news and info allow it to adopt itself as a chameleon-like object”

However, embedded in this seemingly random arrangement of quotidian objects are textual artefacts that might tell us about the world outside of the painter’s personal sphere. An awareness of societal happenings is unavoidable in the experience of Collier’s paintings. Folded newspapers bring current events into the periphery; various copies of the astronomical pamphlet ‘Apollo Anglicanus,’ dated 1676 in one painting and 1701 in another, fix the pinboards within precise years, and transcripts of Her Majesty’s Speech (Queen Anne) act as timestamps marking the succession of a new monarch in England. The inclusion of a material culture – letters, political tracts, newspapers – on these pinboards also allows for engagement with the cultural shifts of the period. Taking a detective’s eye to these paintings, one might uncover evidence of the media revolution of the 17th and 18th century, which saw the printing press become a popularised method for circulating information cheaply, swiftly, and widely.

The quodlibet’s personal-yet-private spontaneity, as well as its being a nexus of news and information, allow it to adopt itself as a chameleon-like object. It is, at once, both seemingly domestic, yet also a tool for propaganda and voicing political affiliation. Recent painters of the quodlibet appear to use the form for similar purposes. Lucy McKenzie, for example, in her series of 2014 quodlibets, mines material from her own cultural and political background. Her use of zines from the ‘Riot Grrrl’ movement, an explosion of feminist punk culture in the 1990s, lifts a traditional painting style out of its antiquated context, reimagining it through a wildly different subject matter.

As history has revealed, the pinboard is not only a medium for self-portraiture, compiling elements of one’s personal identity, but a compendium of one’s society and time. There is nevertheless a danger here. From the quodlibet, the modern pinboard has learnt its mode of self-fashioning – a shaping of both the individual and of society. Nevertheless, this early modern form also teaches that the dangers of superficial or dissembling forms of creation disguise themselves as genuine. We ought to reconsider why we create our modern pinboards; is it for our own pleasure, an authentic attempt to represent one’s voice, or a fabrication of identity that creates a false existence of a self who doesn’t really exist?

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026