Unexpected Nostalgia: On Revisiting my Childhood in Kettle’s Yard

Anna Piper-Thompson finds something disarming and disquieting in Kettle’s Yard’s most recent Alfred Wallis exhibition

On The Last Day of Freedom before the second lockdown, I visited Kettle’s Yard to view the Alfred Wallis Rediscovered exhibition, Alfred Wallis (1855-1942) being a Cornish fisherman and influential modernist artist who was a member of the St Ives Art Colony.

I had been wanting to visit the gallery all term; it was one of the few Cambridge-bucket-list-worthy things that Corona would permit me to do. What I realise now – entering Kettle’s Yard as a Fresher, experiencing the first twinges of homesickness, about to have what little freedom I had found curtailed – is that my visit was fate (and yes, I am a fate-believing, knock-on-wood sort of girl).

This exhibition came with an experience I was entirely unprepared for: a complementary pang of nostalgia. What was my childhood doing, mounted on a wall in Cambridge, 330 miles from the place where I grew up?

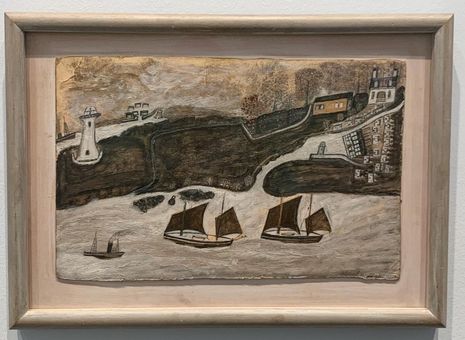

I was lost to these paintings. They are not realist by any means, but that is the point. It is, perhaps, their energy and whimsical approach to perspective which allowed my childhood to echo through them. In other words, it was simply my own self-projection that took me back. I saw myself running over the crayon marks of the sand, my child’s feet playing in the foaming acrylic paint.

“He often used scrap cardboard or items washed up on the shore, allowing the bends and marks to guide his art rather than fighting against them.”

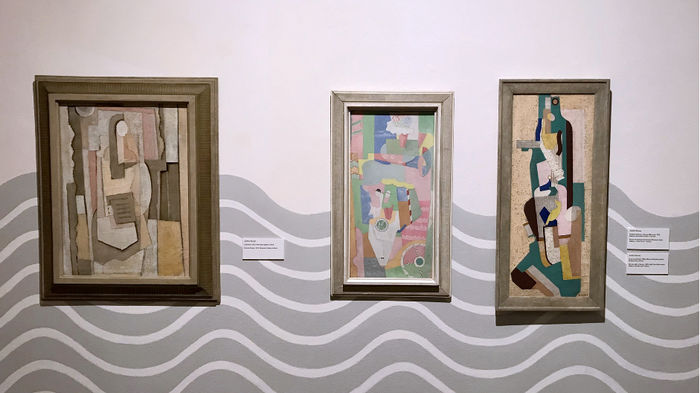

As the Technique and Style section of the exhibition demonstrated, one of the most appealing aspects of Wallis’ art is his use of unconventional materials. He often used scrap cardboard or items washed up on the shore, allowing the bends and marks to guide his art rather than fighting against them. This grants his art a quality of free movement which mimics the natural and irregular flow of the waves he paints – waves on which the artist and onlooker are frequently placed within. In these times of lockdown, we could all take a leaf out of his book and delve into the search for freedom and self-expression within the limitations we are faced with.

He has a playfulness that is embodied in his art across a range of mediums, from entirely purple crayon sketches to painted vases to acrylic paint on cardboard still bearing the pin marks from when he hung them on his own wall. A bit of Cornwall, and his life, is held within these scraps of cardboard (mostly from grocery boxes, as it turns out).

“I had known that port; there was something so intimate about it.”

Wallis said that he turned to art “for comfort”, to combat loneliness after the death of his wife. His works are a patchwork, often drawn from memory. My own memories materialised in the stitching. I don’t know how long I spent staring at one particular painting, Two Ships and Steamer Sailing Past a Port, but it was long enough for my housemate to strike up a friendship with another gallery visitor. She was showing him her sketchbook when I snapped back to reality, my adult feet unexpectedly planted on an unfamiliar white floor. I had known that port; there was something so intimate about it.

I bought three postcards of the piece. I sent one to my grandma, one to my mum, and kept the third to pin to my notice board. Surprisingly, they had also seen exhibitions of Wallis’s work and recognised his distinctive style. It got me thinking about art, how it joins people together and travels through time and place, how our views on it change depending on where we see it. For me, this art was nostalgic, but for my Mum who viewed it in the St Ives Tate “years ago”, it was like seeing through a window with another’s eyes. Often, it is hard to tell, in such an uncomfortable masking, whether one enjoys the view. I certainly did.

In any case, Cornwall now lives, fragmented, in all three of our homes, none of which look out onto the bay, all of which are miles from the sea. We can all look at these postcards and think of each other, and of Cornwall. Art can be a vessel for remembrance, for self-projection and meditation, and sometimes for company, both for the artist and the viewer. In many ways art belongs to all of us, in more than just the pinning of a replica to a notice board, or a magnet to the fridge. It gives us a new window into our own lives.

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026