Book Review: The Art of Rivalry by Sebastian Smee

The Art of Rivalry charts the frenetic relationships between four pairs of artistic ‘frenemies’. Ana Persinaru finds a lot to love about the book, and a lot to question as well.

The myth states that the artist must be a solitary and deeply interiorised character if they are to become a genius. Isolated from their schools or genres, artists are more often than not described as if they worked in a closed-off pod all by themselves, only fleetingly aware of what was leaving other studios. The Art of Rivalry is a zingy and compellingly written account of four sets of artistic ‘frenemies’ in modern art that peels away at every page of that prevailing myth.

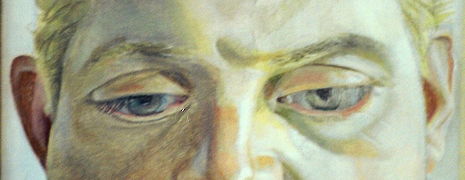

Sebastian Smee, author and art critic, writes with a lot of maturity and penchant for detail about the ups and downs of the relationships between artists, from Manet and Degas to Matisse and Picasso; Freud and Bacon to Pollock and de Kooning. Each chapter in the book is anchored to a three-year period that represented a turning point in the artists’ careers, described in a Woody Allen-esque style; The tension in Lucian Freud’s studio is palpable as he sits knee to knee in front of Bacon, his friend and rival, slowly contouring the sinuous lines of his now-lost portrait. The stories of these artists’ relationships are presented as rollercoaster tours of their turbulent minds, with images and episodes popping out from their memories.

"Who wouldn’t be outraged by de Kooning stealing Pollock’s mistress just months after the latter’s death in a car crash?"

It’s a ride with good and bad turns. Manet slashes the portrait of him and his wife that longtime friend Degas had made but they manage to remain friendly even after his outburst. The motif that Smee weaves into every storyline is that his perception of rivalry within the art world is not one of the ‘macho cliché of sworn enemies, bitter competitors, and stubborn grudge-holders slugging it out for artistic and worldly supremacy’, which is what probably most readers are intrigued by when picking up his book. No: his notion of rivalry, one that every artist undoubtedly faces in his career, is softer and bohemian, relying on the magnetic attraction between two brilliant minds creating in the same space and at the same time. Inevitably, genius artists come with big egos; more often than not, this leads to their personalities clashing.

This is what makes it rivalry in the sense of ‘frenemies’, because no matter how much two artists might appreciate and learn from each other, they are not prepared to create in the shadow of someone else. Acknowledging that influences within the studio came from real-life relationships between artists is realising that one without the other would likely have never achieved their status of masters: Picasso would not have pushed the boundaries of modern art with Cubism without the pressure of Matisse’s bold use of colour, and neither Freud would have relaxed his lines without Bacon’s influence.

What makes The Art of Rivalry a particularly entertaining read, and not just an anthology of modern art history, is Smee’s amazing insight into the artist’s lives and inner lives. The four chapters and relationships are peppered with jealous outbursts, sharply critical comments and fallings out, making this a page-turner for those who get a kick out of intrigue. And Smee definitely did well in using the artists’ temperaments as starting points: who wouldn’t be outraged by de Kooning stealing Pollock’s mistress just months after the latter’s death in a car crash?

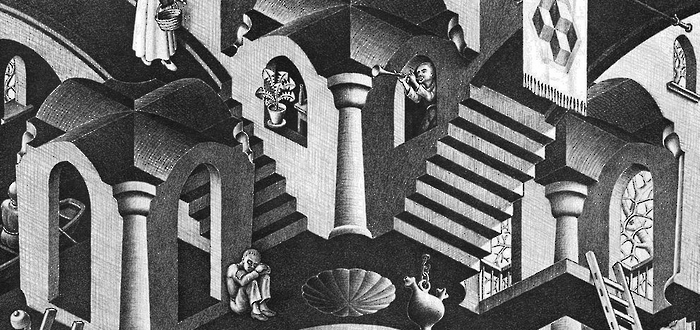

Beyond the great writing style, extensive research and recurring motifs that unify the chapters, however, this book is not without faults. For one thing, the visuals are lacking. The only photos in this book are crowded onto a few pages and awkwardly placed in the middle of the volume, meaning you have to keep flicking back and forth. It might be a slightly pedantic point to make, but we are talking about an art history book which would naturally warrant more generous images, spread evenly throughout the text.

The other point worth raising is the fact Smee doesn't address the ‘other half’: female artists. In an attempt to excuse himself and wriggle out of feminist criticism, Smee mentions his male-dominated narrative from the outset, a bold move with a decidedly pragmatic underlay. He attempts shelter beneath the well-known fact that society and the art world have both been historically patriarchal systems at the time, and feels like the reader will be appeased when learning that he initially thought of addressing the under-representation of female artists in the modern period, working side by side with their male counterparts at the same time - Georgia O’Keeffe, Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot, Tamara de Lempicka to name just a few. In the end though, he felt more at ease talking about the more professional purely homosocial relationships that are ‘uncomplicated by the romantic component that tends to overshadow rivalry [with] passion or chauvinistic condescension’.

Almost a century after these artists entered the scene, it’s disappointing to still see them not taken as seriously as their more audacious male counterparts because of the prejudice of women’s supposed tendency to make a soap opera drama about any man in their life. Smee therefore subscribes to the same tradition of critics dismissing women as equal artists to men by not treating them with the same importance, a pretty damning thing in 2017 but one which is sadly not all that surprising.

In the meantime, all we can do as readers is take notice of his approach and build a constructive discussion about it, whilst still appreciating The Art of Rivalry for the way it portrays male artist relationships in the modern period. More specifically, this would make a suitable read for freshers and finalists alike, who might find solace in knowing that every chapter has a narrative focusing on the uphill struggle these brilliant artists faced before their efforts were recognised. What mattered in the end was their relentlessly disruptive attitude towards pushing forward through prejudice and a wavering level of support from the public

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026