Where dem girls at?

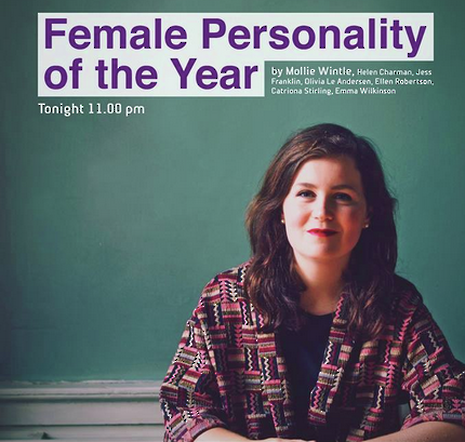

As Female Personality of the Year opens next week at the ADC, Ciara Nugent ponders upon women in the Cambridge comedy scene

'All-male comedy show takes to the ADC stage!' is not a headline you are likely to come across (unless the quality of Cambridge’s student press drops dramatically this year). Yet the same can’t quite be said for 'All female comedy show takes to the ADC stage!'. It might not be the best headline, in fact I really hope we’ve come up with something better for this article, but it is still newsworthy. When Female Personality of the Year opens next week, its female creators won’t just be satirising the representation of women as ‘other’ in the media, they will also be (inadvertently?) challenging their own otherness in comedy.

Why does the team behind this show stand out so much? Why do so few Cambridge comedy shows feature more than one female performer for every three or four guys? Is it because the Footlights committee have a burning misogynistic desire to keep women off the stage? Do they hang sexist signs on the door of smoker auditions? Do they secretly remove any name that might belong to a girl from their mailing lists? Even the Alex's and Charlie's just to be sure? Probably not.

In fact, Cambridge is a far friendlier place to be a female comedian (and indeed a female) than most. Natalie Haynes recently wrote about her experience of misogyny in comedy for The Independent. It’s hard to imagine a Cambridge setting for stories of being openly told by promoters that "a woman couldn’t headline their club, and few bookers would consider having more than one woman on a bill at a time". Here most male comedians seem to lament the scarcity of their female colleagues; would-be sketch groups often find themselves under pressure to ‘find a girl’, not only because it’s socially important but because single-sex sketch groups can only do single-sex sketches, which just isn’t as fun. What’s more, thanks to Cambridge’s unusually strong feminist movement and disdain for lad culture (with a few exceptions), there’s very little Al Murray-style sexist comedy that might put off any girl willing to give it a go. These factors, combined with the university’s almost ridiculously active and respected comedy scene, should make it an egalitarian bastion for the fostering of funny girls.

While this is the case for some, such as the incredibly talented team behind Female Personality of the Year, one need only look at the casts of shows coming up this term to see that an extreme gender imbalance still exists. And, without wishing to focus too much on them, only two Footlights presidents in the last 20 years have been women, and these have been a really good 20 years.

The short supply of girls willing to audition for smokers and sketch shows clearly doesn’t stem from stage fright; female actresses tend to outnumber the boys at play auditions in the equally booming drama scene. Why then, for all Cambridge’s progressive politics and open opportunities, is comedy the one place feminism can’t quite reach? The depressing answer is that no university, not even Cambridge, can erase the years of cultural conditioning most of us undergo by the time we arrive at university at 18 or 19. We’re talking gendered traits and oppression, and while these are obviously my favourite subjects they’ve been discussed many times before, by people with doctorates and higher word limits. So, I will condense the issue into one paragraph.

It comes dow to a cycle of cultural expectations. In the words of Marie Wilson from the White House Project, "You can’t be what you can’t see". In comedy terms, this means girls grow up seeing ‘funny women’ as people like Katherine Heigl or Jennifer Aniston in romantic comedies like The Ugly Truth, Marley and Me and Knocked Up. These films, almost always written and directed by men, often constitute young girls’ first contact with mainstream comedy. They invariably cast an amiable and attractive woman as the ‘straight man’ to the hapless, zany male protagonist who causes trouble and a whole lotta’ laughs. Therefore, girls learn from a young age that what is important about them is their appearance and their ability to get along with others, encouraging passivity and an uncritical disposition over the development of wit and confidence.

Comedy is a delicate bird, requiring a lot of the aforementioned confidence, along with positive expectations and the ability to shock; to inhabit many different roles at once, an ability which is consistently denied to women who tend to be seen only as ‘women’ rather than ‘multi-faceted people’. Thus, the cultural conditioning of audiences also undermines the success of female performers- girls and boys alike learn to expect women to be less funny than men. Even in social situations, the classic dynamic of "That’s a great suggestion dear, perhaps one of the men in the room would like to make it?" often occurs; girls’ jokes are ignored as everyone keeps their comedic ears pricked for what the boys might say. After a while the girls just stop trying. So they grow up, and they don’t make as many jokes and none of them become comedians and then some idiot uses that as proof to tell them, "You see! Women aren’t funny!"

This sad, sad situation is mitigated by two factors. First, many girls are clearly able escape this cycle and that’s how, amongst the sea of funny men in Cambridge, we’ve got many shining examples of funny women. Second, culture is not unchangeable. I think the way existing female comedians have managed to overcome the aforementioned cultural conditioning is largely by being unaware of it. They thought they could be funny so they let themselves be. They made themselves be. When we have kids, we can (and we should) shelter them from patriarchal ideas of who is and isn’t funny. We should tell our daughters to be funny, not pretty. We should tell our sons to like girls who make jokes, not cakes. Other patriarchal social structures, like the gender pay gap or rape culture can affect anyone, no matter their personal beliefs. But when it comes to this one, this particular stumbling block in the path to equality, I think that by not knowing it exists, or at least by refusing to believe in it, we can destroy it.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025 News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025