William Shakespeare’s A Christmas Carol is a fun innovation of the Dickens classic

To be or not to be a Scrooge? This production aptly demonstrates that characters can change, with versatile performances of this literary fusion.

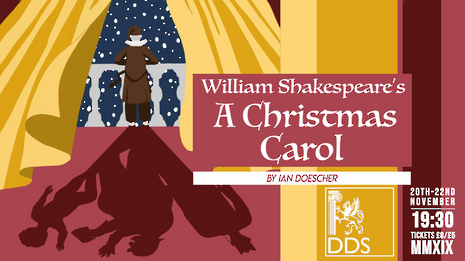

At this time of the year, togetherness becomes the key mood, and in William Shakespeare’s A Christmas Carol two unlikely literary stalwarts are brought together in a reinvention of the classic festive story. Taking the plot of the Dickens novel and introducing the Bard (accompanied by some of his foremost characters), this play presents a Christmas story like no other – one that Director-Producer Zev Shirazi successfully brings to the Howard Theatre.

Ebenezer Scrooge (Gregory Miller) does not give up to his miserly habits, but, in William Shakespeare’s A Christmas Carol, he becomes a theatre owner. His dead associate is no longer Jacob Marley, but Christopher Marlowe (Keshav Nehra), who appears in chains as in the original version, which is actually not so different from this reimagining. The innovation of the script is rather about characters than about the action itself, and Shirazi chose to largely follow the not-so-beaten path suggested by the playwright Ian Doescher.

“Both Miller and Nehra proved their tremendous flexibility and capacity to engage the audience.”

The most ambitious role was definitely Miller’s, who outstandingly shifted from the initial bold Scrooge, to the humble one who takes the stage in the end of the performance. In only two hours, the actor changed from a crabby old man talking to people in hurtful tones into a fun-loving, refreshed and sweet character, just as if Miller had played multiple impersonations. Scrooge writhes on the ground, haunted by his death as unveiled by the Ghost of Christmas Future and, ten minutes later, the same character spreads joy in the auditorium through jokes and optimistic wishes. A complex and versatile role was played by Nehra, as well, since his Marlowe catches attention either with his concerned, remorseful remarks or with funny, quirky calls intended to strike Scrooge with guilt. Both actors proved their tremendous flexibility and capacity to engage the audience, especially as the two of them were also in the spotlight during soliloquy moments.

In the case of the other three ghosts, of Christmas Past or Puck (Katie-Lou White), of Christmas Present or Falstaff (Maddie London) and of Christmas Future or Spirit of King Hamlet (Seth Daood), the challenge for the actors must have been double, as the traits of the characters were transferred almost in their entirety from the original Shakespearian plays. The first two ghosts’ performances were lively; the quick-witted Puck and the rebellious, erratic Falstaff animated the atmosphere while preparing the audience for King’s Hamlet appearance. His moment was rather silent and his lack of response drove Scrooge to despair. Daood compensated the taciturnity of the character with evocative, slow body movements that added suspense to the performance.

This show's major innovation consisted its way of handling space. On stage, a piece of furniture would make the distinction between Scrooge’s bedroom and other past, present or future locations. Moreover, the characters ambled around the auditorium, the extension of the stage being used during the protagonist’s recollection, as handled by Puck. In the last part of the performance, a reversed tombstone with the main character’s name engraved on it kept the audience hooked. The production took advantage of the light in order to suggest either times of the day (blue light was associated with the night) or to focus attention on the soliloquy moment of Marlowe, for instance.

Rose Schechter and Caroline Katzive’s costumes call to mind the Elizabethan fashion – Scrooge is wearing a white, ruffled neck collar, while many of the characters wear black and white clothes. Some of them were dressed extremely colorfully (Juliet - Grace Beckett – was attired in pink); nevertheless, the point the costume designers wanted to make through this choice was probably not obvious enough for the regular target audience. Neither was the approach of Christmas time suggested at all by means of costumes or set.

Even though, in the end of the play, the festive atmosphere was established more fully and directly, it was still not enough. This may have been intended as an ingenious way to give a sense of generality and recurrence to the situation described in the performance even outside the celebration time, but for me it was one of the very few and ultra-fine flaws that keep William Shakespeare’s A Christmas Carol from being among the best performances of this term.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025