Ihave always enjoyed immersing myself in the colourful, atemporal, high-society greenhouse of the gallery as a determined disciple of the arts, stubbornly trying to fit in. Notebook and open mind at the ready, I stave off the dreaded ‘museum fatigue’ to absorb as much inspiration, and information, as possible – especially if the entrance fee was pricey. I don’t mind feeling unfamiliar or undereducated, and often revel in the unprecedented access to the arts that being a student or a local allows; quietly mimicking the cult of pretentiousness has felt like a day pass to that exclusive world. Yet, a recent visit to the Tate St Ives with my younger, very art-averse brother brought my doctrine into question, and left me wondering what a decidedly unserious approach to consuming art can offer.

Perusing the Tate St Ives’ new exhibition Ithell Colqohoun: Between Worlds, dubbed “thrilling” and “visually hypnotic” by The Guardian, my 15-year-old brother found entertainment not in the twentieth-century surrealist painter’s “ecstatic chromophilia”, but in the pieces’ scope for humour. As we contemplated a Slade competition-winning depiction of Judith and Holofernes, a gory Old Testament story, he remarked of the severed head spurting blood: “Look at that cheese pull!”

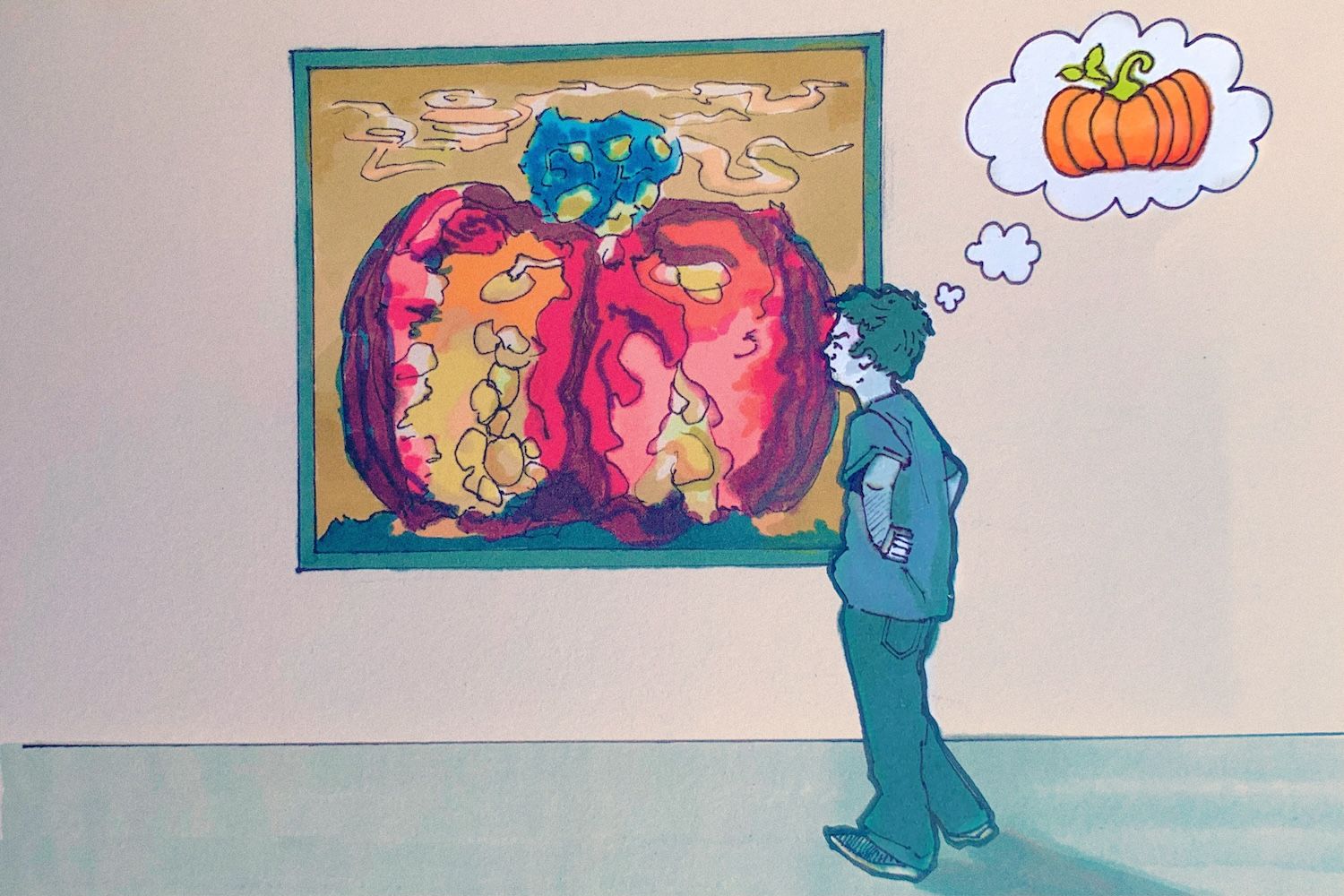

I laughed out loud at his sarcastic throwaway comment, and felt relieved at my usual pensive silence having been broken. For the rest of the exhibition, I took myself less seriously: I moved on briskly from a painting if it didn’t resonate with me or simply, by my standards, wasn’t very good. And as the artworks became more abstract in their surrealism, my brother’s comments became more actively undermining. On viewing a pair of twin ink-blots that Colquhoun had interpreted as opposites, one an angel and the other a gorgon, he announced: “No, that’s a pumpkin!”

While at first I rolled my eyes at his lack of engagement, I realise on reflection that this off-the-cuff reaction was not so different from the surrealists’ own Freudian automatist approach to art. Achieved here through the use of decalcomania – blotting wet paint, folding and pressing the page to create a mirror image – automatism refers to creating art which bypasses rational thought and instead accesses the unconscious mind. Colquhoun’s mythical interpretations of such a technique might appear to some as radical works of genius, but I wonder: what makes her occult, privately-educated perspective more valuable than my teenage brother’s inventive comedy?

Let us return to an arguably simpler question: what is a gallery for? Optimistically, for the democratisation of the arts. Pieces worth thousands or millions of pounds, prized for their cultural significance and otherwise hoarded as the trinkets of the uber-rich are collated and displayed in spaces often also reserved for the upper echelon of society. Untouchable they may be behind their red tape and bulletproof glass, but the general public is permitted at least full, in-person visual access to the art world.

How to occupy such a space is our next concern. Emile Zola proposed that when looking at art, one must search for the artist behind it, and Van Gogh was reportedly a voracious reader of artists’ biographies. For them, the gallery represents a space of seeking, acquiring and consolidating knowledge about art history – a view which many active consumers of art maintain today. Yet, even for the invested visitor, the modern gallery is becoming increasingly less about accessibility, and increasingly more about the heralded ‘art’ of curation.

As Lily, an Art Historian at Christ’s, told me, the “sheer amount of visual culture” in such spaces is overwhelming, and “the inaccessibility of the gallery is that they don’t provide enough information”. At times, plaques offer almost nothing – perhaps just an artist’s name or the title of a piece. And at others, pretentious jargon makes what information there is entirely alienating for the average person. As academic Gregory Rodriguez puts it, “labels emphasising shifting techniques of craft, highfalutin intellectual concepts, or the minutiae of artistic movements seem to be written by PhDs for PhDs.”

With cultural institutions fighting to stay alive, this didactic approach to displaying art seems to be unengaging and inefficient, failing to appeal to what Rodriguez calls “primary human themes”. As we wait for stubborn galleries to catch up, untethering our own responses to gallery works can offer its own reimagining of art as an opportunity for emotional, rather than intellectual, consumption.

“As we wait for stubborn galleries to catch up, untethering our own responses to gallery works can offer its own reimagining of art as an opportunity for emotional, rather than intellectual, consumption.”

Studies have already shown that this emotional response is chemically quantifiable. Viewing art which is beautiful in the eye of the beholder can create an instant dopamine release similar to the feeling of looking at someone you love, and psychologists have identified a link between looking at subjectively ‘good’ art and increased brain activity in the areas associated with self-reflection and recollection. Science, therefore, offers its own argument for experiencing, rather than blankly learning about art; when we are guided by our intuitive reactions, we are able to access higher-level processing networks.

But what about art that we judge to be subjectively ‘bad’? Speaking to illustrator and concept artist Warwick Tregoning, he told me: “I don’t believe an artist’s intended reception of the work should be the only way it is enjoyed given the purpose of art is to be interpreted by the viewer based on their own experiences. If that work doesn’t resonate with them, it has still fulfilled its purpose of engagement with the viewer in producing an emotional and or physical response.” As many people say, art is first and foremost meant to make the viewer feel something, or feel something, whatever that may be.

Yet, as both Warwick and Lily stressed, this openness must come with context and nuance. Warwick notes that when we consider how seriously to approach art: “I think this is a situational case; there are many galleries and exhibitions where I feel work should be taken seriously but there are others that invoke a more playful response.” Lily also points out the importance of cultural sensitivity: “Sometimes artists will be using a visual language that we are not familiar with, and to us it seems bizarre and humorous but actually to them it could be expressing something really serious.” While galleries should not make us feel small or underinformed, if our personal aversion upon viewing a piece for the first time does not come with any attempt to ask why, we are doing ourselves a disservice.

When we are conscious of the social context of art and its institutions, a cynical or humorous perspective can then offer an active mode of individual revolution against culturally entrenched norms. After all, far too often the art lining the walls of the Tate or The National Gallery are the work of European, classically-trained artists of centuries past – or the abstract, minimalist creations from the ivory towers of contemporary artists.

“When we are conscious of the social context of art and its institutions, a cynical or humorous perspective can then offer an active mode of individual revolution against culturally entrenched norms”

As one Newnham student told me, making jokes at the expense of these removed figures can be “comforting because it feels like the only tool I have to undermine elitism that seems much larger than I am.” Rather than being an act of pretentiousness or “seeing myself as above it, I see myself as essentially below it. Sometimes it’s empowering to hate on a social sphere from which you have felt excluded.” Critical or even mocking conversations about fine art and galleries have little to no tangible impact on the people and institutions behind such spaces. Rather, they allow the viewer to acknowledge and question the social apparatus which shapes our access to culture without alienating themselves from experiencing art at all “out of protest,” which would be counterproductive.

It remains unlikely that my teenage brother is consciously punching up at the enduring snobbery of the art world with his well-timed jokes. However, his physical and emotional presence in the space is important. It represents a kind of democratic, bottom-up curation which, if nothing else, sparks interesting conversations around learned gallery etiquette, our responses to art, and the wider forces behind each gold-framed painting on the wall. Whilst humour should be employed tastefully and not replace curiosity, it is a powerful tool in the art consumer’s repertoire, and can be quite transformative when wielded correctly.