The social media boycott garnered momentum. Now it’s time for change

Sport Editor Cameron White and Damola Odeyemi argue that while the recent social media boycott campaign built on a momentum of racial reckoning, it must be complemented by political action to avoid becoming merely performative

Football in the UK, along with a range of other sports including cricket, rugby and tennis, boycotted social media from 15:00 (BST) on Friday 30 April to 23:59 (BST) on Monday 3 May. Announced on Saturday 24 April by the Premier League and Women’s Super League, this was a response to the abuse directed primarily at Black players on social media platforms.

Just in the last few weeks, there have been a handful of racist incidents that no doubt fueled the fire in the lead-up to the boycott. Last month, the Aston Villa and England defender, Tyrone Mings, was subject to racist abuse on instagram. This incident sparked some action from specific clubs such as Swansea and Rangers who staged their own social media boycotts. The racism in football does not lie only with the fans; it exists on the pitch too. One high-profile case involves the Slavia Prague defender Ondrej Kudela receiving a ten-match ban from UEFA after racially abusing Rangers’ Glen Kamara in a Europa league match. This was viewed widely as a somewhat soft punishment for such a blatant, serious offence. Meanwhile, in the Rugby League, Tony Clubb, who plays for Wigan Warriors, was charged and suspended for racist abuse towards Hull FC’s Andre Savelio, a New Zealander of Samoan descent. And just this week, Hertha Berlin sacked former Arsenal goalkeeper Jens Lehmann from a consultancy role after he sent a WhatsApp message containing racist content to former German footballer Dennis Aogo. While this was far from being the first social media boycott of the past year, it undoubtedly involved the largest collective number of clubs and other governing bodies across a range of sports, along with sports press and broadcasters, such as the Guardian and Sky Sports.

“...the value of this boycott is in the momentum it is latching on to and building upon”

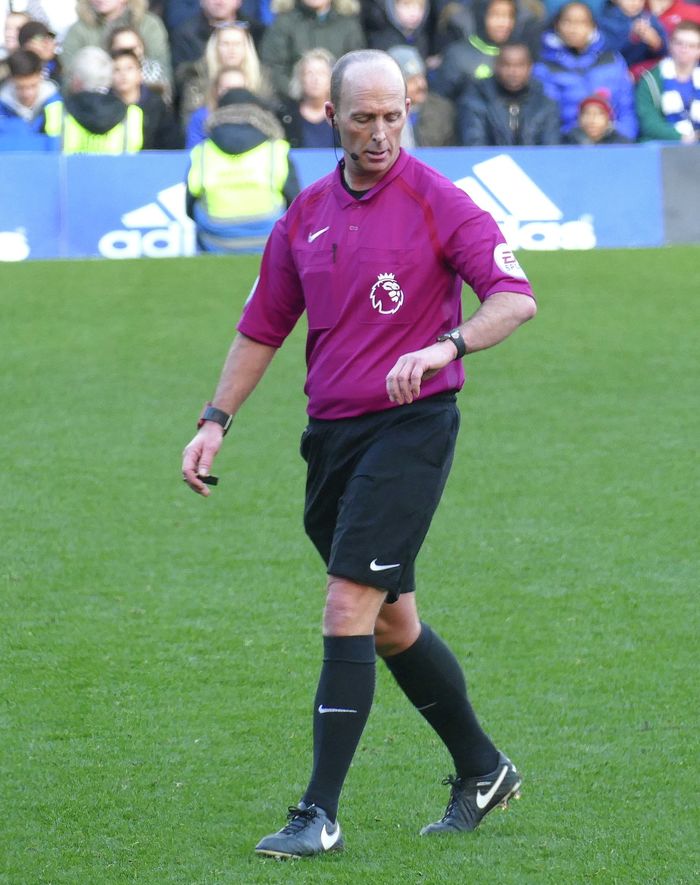

The boycott aimed not just to raise awareness about racism and other forms of discrimination, but also to emphasise that social media companies must do more to police their platforms and protect its users from abuse. This all comes after a somewhat turbulent six months or so, where players have felt more confident to report the abuse hurled at them on social media. Many football authorities, notably the FA and Premier league took notice of the abhorrent ways in which Black players were treated almost on a weekly basis. To make matters worse, in January, referees and other match officials were subject to death threats on social media. The solution to this problem does not lie with the players or referees. They should not have to delete social media to escape mistreatment; that would simply be yielding to the anonymous culprits. The social media companies themselves have been called upon to provide a solution, to police their platforms by removing offending individuals, in order to make it a safer space, particularly for black players and referees who receive the most abuse.

“...it is imperative that such campaigns as the most recent boycott drive political change, and avoid becoming clichés”

This raises the question of what exactly this boycott can achieve, or whether it is simply a performative act. It goes without saying that this act on its own will not change anything, and is admittedly performative, much like any other action that doesn’t directly target the source of the problem. However, the value of this boycott is in the momentum it is latching on to and building upon. The fact that so many parties are involved, elevates the public profile of this demonstration. It is a reflection of the collective anger felt by the football community concerning the mistreatment of Black players, with Thierry Henry, the renowned Arsenal and Barcelona forward, quitting social media over racial abuse and bullying . 2020 was a year of racial reckoning and the footballing authorities are now coming to terms with just how much social media potentiates abuse of players and officials. In taking a stand, they are signalling to the players they represent that they have their best interests at heart.

Following the boycott, the overall reaction has been that it sent out a powerful message of unity in defiance of racism and online abuse. However, as the Chief Executive of Kick It Out, Tony Burnett, highlighted in an interview with Sky Sports News, such campaigns must be complemented by legislative efficacy in order to avoid risking performative vacuity.

In particular, the Online Harms Bill, proposed in the House of Lords by Lord McNally in January last year, calls for increased responsibility on the part of social media companies by requesting that Ofcom produce a report of recommendations to pave the way for an Online Harms Reduction Regulator, encompassing among many other recommendations “the prevention of [...] racial hatred, religious hatred, hatred on the grounds of sex or hatred on the grounds of sexual orientation.” While a promising white paper published by the government in December called for “new, global approaches for online safety that support our democratic values, and promote a free, open and secure internet”, it is time for these commitments to become the letter of the law, with an Online Safety Bill due to come into effect this year. Nonetheless, it is imperative that such campaigns as the most recent boycott drive political change, and avoid becoming clichés unaccompanied by legislative action.

After fans put away their differences and came together to protest against the European Super League, some have asked why this level of activism and fervour is not shown in the fight against racism, as lamented notably by Leeds United striker Patrick Bamford. This boycott looked to take the momentum from the previous week and direct it towards a more pressing cause. The 48-hour period that the ESL lasted for is a perfect display of just how powerful supporters and clubs alike can be if they come together against a common adversary.

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026

News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026 Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026

Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026