Social Media: A lawless world of abuse

Following a concerning recent rise in online abuse, Damola Odeyemi considers the personal toll for those on the receiving end and how best to combat it.

On Wednesday 28th January, after a surprising 2-1 defeat to Sheffield United, and 9 days later following a 3-3 draw to Everton, the Manchester United defender Axel Tuanzebe was subject to racial abuse on Instagram. This was one of the many cases of black players receiving abuse on social media. Tuanzebe was not the only one. Eddie Nketia, Reece James and many more players have since reported and shown evidence of the abuse they receive on an almost weekly basis. Screenshots of people commenting on their posts with monkey emojis were made public, prompting the Premier League to condemn social media companies for not taking action against racists on their platforms. These incidents revealed the systemic nature of the abuse directed at black players. Many of them have been dealing with this treatment from the youth level. It can be described as almost ‘routine’ for black players to be racially abused on social media after bad team performances, while their lighter-skinned counterparts, their teammates, are left relatively unscathed.

“It is the responsibility of social media companies like Instagram to protect users from abuse and bigotry.”

In terms of finding a solution to the problem, there is little that the Premier League can do to protect the players. When fans were in stadiums, any offenders could be tracked down and punished accordingly. The punishments ranged from lifetime bans, to being sentenced, to time in prison or community service. Now that the abuse is all online, clubs cannot trace the culprits, who tend to be using anonymous accounts. This is why the Premier League and the FA have approached social media companies to police their own platforms and put an end to this systemic abuse.

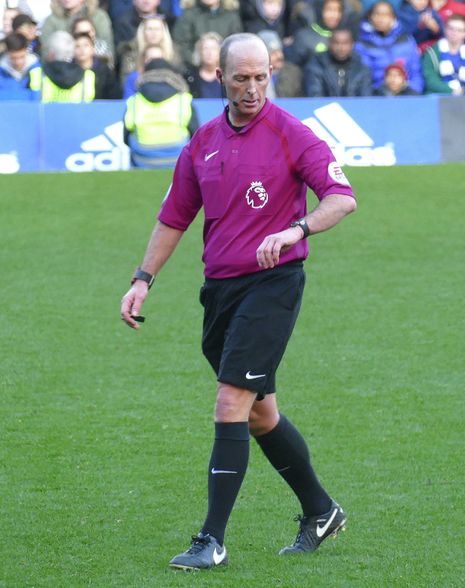

This rise in abuse has also been directed towards match officials, most recently regarding two specific decisions made by Lee Mason (VAR referee) and Mike Dean (on-pitch referee) in the space of 5 days. The incidents involved the sending-off of Southampton’s Jan Bednarek and West Ham’s Tomáš Souček. Highly controversial at the time, the decisions were soon deemed incorrect and overturned. The two incidents, quite rightfully, called into question the use of VAR and the broader issue of our interpretation of the rules of football. However, what grabbed the headlines was the abuse directed at the referees. Referees are used to abuse, be it from players, managers or fans. But nothing is more worrying than hearing of Mike Dean, the oldest and most experienced referee in the league, asking to be left out of a week’s matches as he and his family had received death threats in the days following the overturned decisions. The same applied to Lee Mason, who has now stood down as a Premier League referee.

“VAR has taken away all of the referee’s authority, leaving them vulnerable.”

Most people assumed that VAR would make referees’ jobs easier, that it might take uncertainty out of the game. But it has done quite the opposite; their jobs are much more difficult, and VAR has made referees even more of a topic of discussion. In the lower levels of football, we classify a good referee as one with control and consistency – some give soft fouls, some shout play on, but as long as they are consistent and confident, there is little need to discuss them. However, in elite professional football, gone are the days of referees having total dominance over the proceedings on the pitch; VAR has taken away all of the referee’s authority, leaving them vulnerable. Referees’ decisions, now under constant scrutiny, can be overturned within minutes. Consequently, they are less confident in their decision-making. Offending fans recognise any sign of weakness and don’t hesitate to pounce on it.

The past few months have seen an upward trend in mistreatment of black players and referees. Regarding black players, this is likely only an increase in cases being reported; unfortunately, black players have always been subject to this sort of alienating treatment. As with much of society, racism is still engrained in the sport and in its fanbase. Social media simply presents a platform for that racism to have more penetrative and damaging effects on players. This is a similar case with referees, rendered vulnerable by VAR; they are now possibly experiencing some of what black players have to live with on a weekly basis. Neither black players nor referees deserve the abuse coming their way, and the common factor is social media. We cannot expect the victims to leave social media to avoid abuse. That, in a certain way, is conceding to the will of the offenders. It is the responsibility of social media companies like Instagram to protect users from abuse and bigotry.

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025