During the last few weeks of term, I’m sure you noticed how exam season meant more consistency in routine, people, thoughts, and feelings. It became a quasi-robotic rhythm: breakfast, library, lunch, library, dinner, library, and dreaded sleep, only to start all over again. The days begin to merge, framed only by the countdown to the next paper and the distant promise of a final moment of relief. Conversations with friends start to recycle and mutate into the same shape: exams. Any deviation can feel transgressive – as if talking about anything else was a distraction from the ‘important’ things, or even worse, a guilty admission of not taking things seriously enough.

It sounds terrible to admit, but you feel the need to put your life on pause. Of course, our degrees – the coursework, exams, dissertations, stress, and pressure – are all part of life, but so are the other things that make us us outside of Cambridge. Now that exams are over and we’ve (hopefully) had time to decompress, I still catch myself checking emails every morning, expecting urgency. Summer is supposed to offer a break – a kind of relief – but instead, sometimes it offers something else: ambiguity.

Unlike the packed, togetherness of term, summer brings a weird, disjointed space where comparison, insecurity and a slump can germinate. When structure falls away, so does a sense of clarity that comes with being needed, assessed and measured. What do you do with a mind wired for deadlines when there are none left?

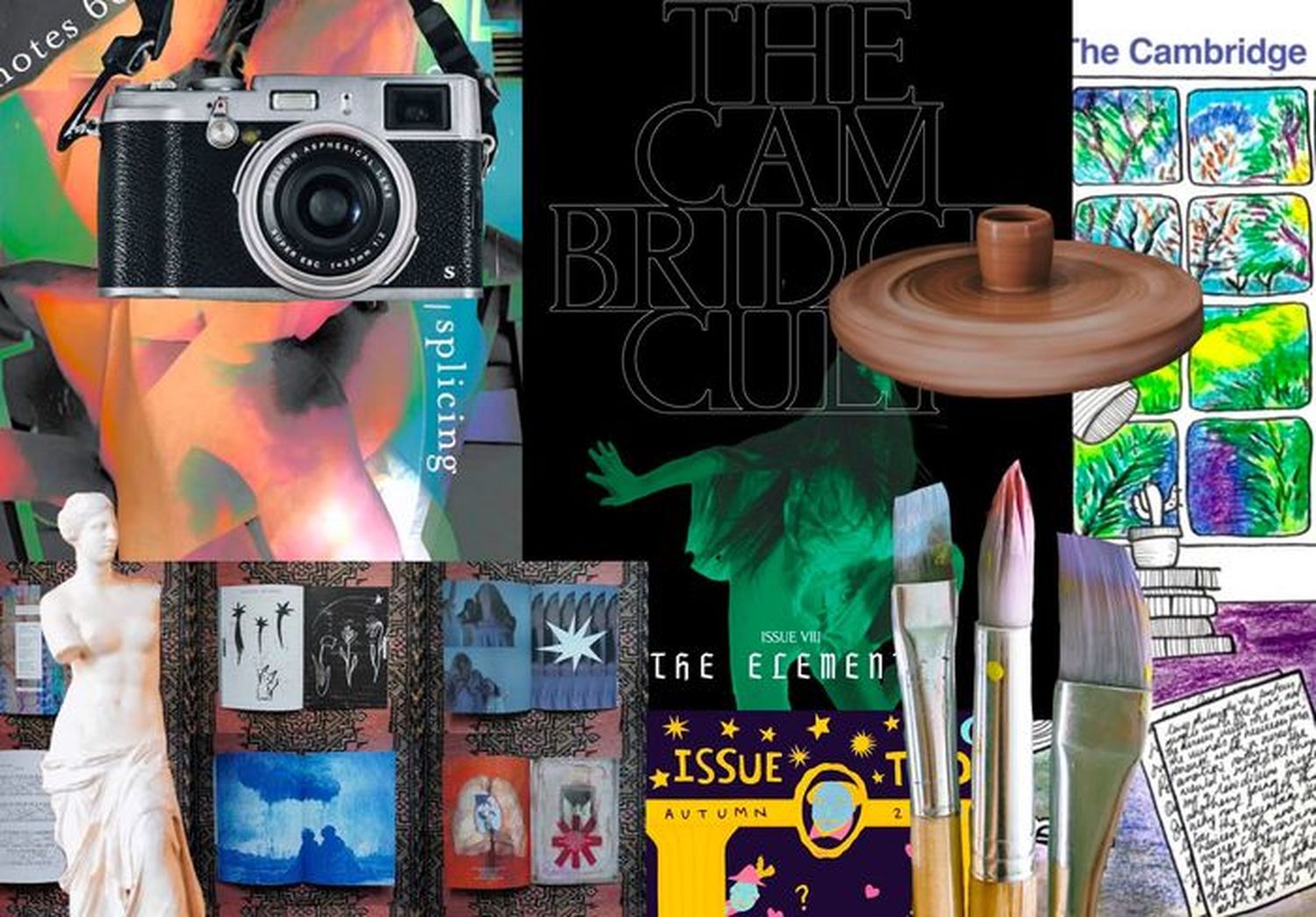

This is where creative practice comes in. I’m not trying to be prescriptive. But I am attempting to suggest that seeking small, introspective, creative acts – during or between term time – is not self-indulgent or wasteful. It might actually be essential. Essential not just as a way to take a break, but as a way to interrupt the vicious cycles we normalise: exam stress, toxic productivity, and even the post-exam burnout we disguise as alcohol-induced May Week euphoria. Creativity allows for a kind of spontaneity we rarely allow ourselves – the surprise of doing something without purpose, without an audience or reward.

There is a quiet cultural aversion – or hesitation – towards this. Maybe because it feels unserious, like a guilty pleasure too frivolous when so much else in our lives demands our focus. Maybe because the pressure to be ‘productive’ – and to prove we are working hard enough – seeps so deeply into Cambridge culture that it can feel threatening. Maybe because doing something for yourself feels selfish in the context of the collective stress of exams or carefully curated LinkedIn updates. And so, is creative activity a distraction – a way to avoid the things we should be doing? Or is it catharsis – a process that allows us to cope, or to release? Or does this distinction even matter?

Catharsis can most simply be described as a sense of relief, but some speak of it as something that unfolds in the experience of viewing art. Aristotle considered art to erode one’s negative emotions. Drama, literature, and film have the power to absorb us so fully that we are carried through emotion. However, visual art can demand less time (but no less attention), leading to equally powerful effects; a momentary encounter with certain colours, shapes, or figures might trigger this same sense of relief.

“Creativity allows for a kind of spontaneity we rarely allow ourselves – the surprise of doing something without purpose, without an audience or reward”

American abstract painter Mark Rothko’s paintings, for example, were known to literally bring people to tears. Rothko himself admitted he wanted to communicate the “basic human emotions - tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on,” and he welcomed “the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with” his work. It is as if the possibility of allowing artists to move people at a personal level could be the end of somewhat of a “chain of catharsis”.

Other artists, like Henry Darger, show us a different kind of inner necessity in art-making. In 1972, he left his rented room to move to a nursing home, leaving behind a staggering 5,000 page autobiography, a 15,000 page illustrated novel, and several hundred drawings, paintings, and collages. His work is vibrant and obsessive, using comic strip-esque pencil and watercolour to create an epic imaginary world. He is often described as an ‘outsider artist’ because he seemingly never showed anyone his work, but that framing misses the point. Why create, obsessively, privately, if not for some deeply personal need – a processing of thought, memory or desire?

Louise Bourgeois, whose nine metre spider you might recognise from visiting the Tate Modern, spoke openly of the therapeutic roots of her work. She described art as a way to transform childhood trauma into something visible, to be shared and processed, stating “art is a guarantee of sanity.” – It is not indulgent; it’s survival. Perhaps it’s worth distinguishing between catharsis as release – venting – and catharsis as transformation: the slow work of making sense.

We often treat ‘fine art’ as something locked in museums, like Bourgeois’ sculptures or Rothko’s colour field paintings. And yes, those can absolutely be catalysts for catharsis. For me, a moment like that came this Easter at the Fitzwilliam Museum’s ‘Rise Up’ exhibition, when I saw Dido Elizabeth Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray by David Martin (1779). It is a remarkable painting – the staging, the clothing, the barely suppressed grins, the intimacy or perhaps restraint it captures is nearly enough to bring me to tears. It was, in every way, a moment at the end of a chain of catharsis.

But instead of only art trapped in museums, I want to propose a more accessible kind of creative expression: arts and crafts (especially if the Aristotelian definition sounds too grand for you) – a low-barrier, micro-scale conduit to the same effects ‘fine art’ can deliver. The phrase probably conjures up something unserious – paper chains, glue sticks, plastic knitting needles, or beaded friendship bracelets. Or perhaps you think of the Arts and Crafts Movement of the 19th century, led by William Morris, and its attempts to emphasise the creation of handmade art in defiance of industrialisation.

But arts and crafts have a much deeper and wider history as vital means of cultural expression. Think of pashmina weaving in Kashmir, Maasai beadwork, Russian Matryoshka dolls, and Mexican alebrijes. These are not just quaint folk arts preserving a distant heritage – they’re living, evolving expressions of identity. What matters is that crafts emphasise process over product. They are tactile and improvisational; they make space for spontaneity. They are functional and decorative, incorporating personal expression, material diversity, or cultural influences. The distinction between art and craft, if it even exists, often blurs here.

“The phrase probably conjures up something unserious – paper chains, glue sticks, plastic knitting needles, or beaded friendship bracelets”

For some, times of stress are when creative practices are abandoned – sacrificed at the altar of productivity. For others, it’s when creativity blooms. A good friend of time – who inspired this article – channels her historical interests in material culture and object-making through sewing and costume design in her free time. I remember a stunning 19th-century military-inspired frock jacket, reminiscent of the hussar jackets from Decarnin’s 2010 collection for Balmain. During term time, she has less time for big projects, but manages to carve out moments for smaller ones – like crafting a Minotaur-style headpiece for a college bop in Lent, or water colouring posters to plaster across her walls. Now, it might sound unrealistic to suggest that you drop everything to pick up a paintbrush or crochet hook. But, again, that’s not really what I’m proposing.

What I am suggesting is this: find ways to keep spontaneity alive – during exam season, during May Week, and in the ambiguous silence of summer. Arts and crafts aren’t a universal cure for stress, but they are far more than a childish or self-indulgent pastime. Doodle in the corners of your books. Write a terrible poem in your Notes app. Fiddle with a half-finished DIY kit. These small acts are not regressive. They are resistance against the culture of outcome, of optimisation, and of constant proof.

That, I think, is the point. A kind of self-expansion that requires no audience, no competition, no reward. When curiosity gently returns – when you make something, anything, just because you feel like it – that’s when the chain of catharsis begins again. And maybe, if you’re lucky, it’ll reach someone else too.