South Africa’s rugby problems are more than skin deep

Ben Cisneros looks at the decline of the once-great Springboks and what needs to be done for them to return to their former glory

South Africa’s 22-24 loss to Wales a week ago was their 12th loss in the two years since the 2015 Rugby World Cup. While this year has only been half as bad as the previous one, by Springbok standards, it has still been pretty poor.

In 2017 they have failed to beat a team above them in the world rankings, and suffered record defeats against both Ireland and New Zealand. In 2016, there were record losses to Italy, Argentina and Wales, and a first defeat to England since 2006. Throw in this year’s draws against Australia, and last year’s tie with the Barbarians, and their win percentage stands at just 42%. For a nation which has lifted the Webb Ellis Cup twice, and has for so long been regarded as one of the toughest sides in world sport, such a record is unacceptable.

In their defence, they showed great character in Cardiff, as they did against New Zealand in Cape Town, but a one-point win against France – who this month drew with Japan, and beat South Africa to secure the 2023 Rugby World Cup – coupled with a win in Rome leaves them with little tangible to take into their off-season.

There are several interrelated problems which I see as being at the root of this Springbok slump. The first of these is economic. The past few years have seen economic growth slowing and inflation rising in South Africa, amid political uncertainty. Questions over Jacob Zuma’s presidency have been mounting, particularly after the country’s credit rating was downgraded into the 'speculative' category, which has only served to amplify social unrest. Most interestingly of all, the value of the rand has been falling consistently since late 2015, coinciding perfectly with the Springbok decline.

The impact of this economic downturn, and particularly of the falling exchange rate, has been to encourage more and more South African rugby players to move abroad. The wages of the TOP14 and English Premiership have for years been much higher than those of Super Rugby, but the weak rand has amplified the difference. Poor attendances – no doubt brought on by the tight economic situation – aren’t helping clubs generate revenue, meaning opportunities to set oneself up for a life after rugby are increasingly few.

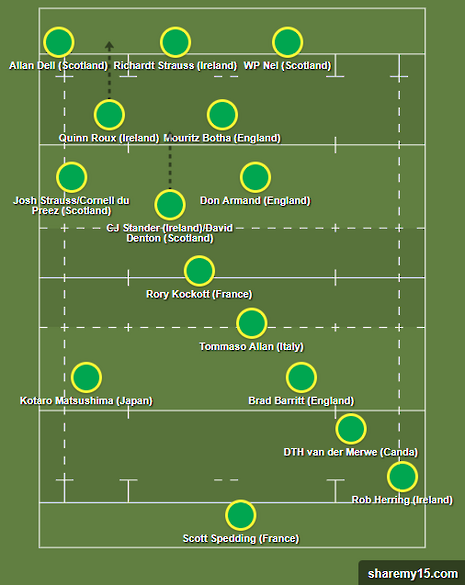

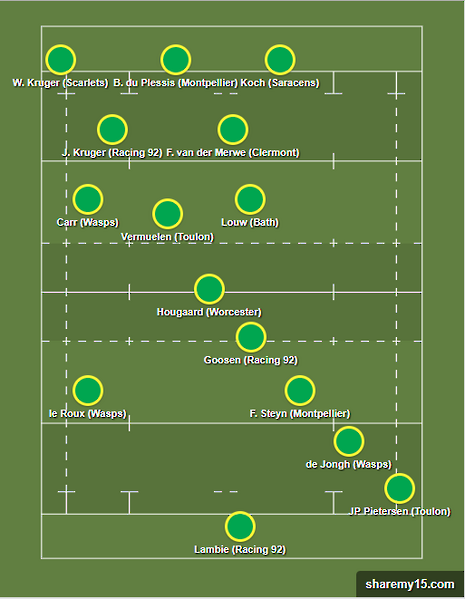

As such, there has been an exodus of both top-flight and young players. As the above graphic shows, there is a plethora of players eligible to play for South Africa who are instead representing other countries around the world. The Pacific Islands are not the only nations suffering from a player drain.

Of course, one of the main consequences of this economic situation is that there has been a weakening of the South African Super Rugby franchises – so much so that two were cut at the end of last season. The Cheetahs and the Southern Kings have found a home in the revamped Pro14, and with it an influx of northern hemisphere cash. The Lions have been the only South African side to make the semi-finals in Super Rugby in the past two seasons, but they have now lost their inspirational head coach, Johan Ackerman, to Gloucester. It is not just players South Africa are losing: Eddie Jones was supposed to be coaching Cape Town’s Stormers before he was snared by the RFU.

The next, related problem is that of overseas selection. As of July 2017, the SARU introduced a new policy, that players based overseas can only be selected for the national side if they have at least 30 caps (except for World Cup years).

The rule itself makes sense. The SARU wants to encourage South African talent to stay in South Africa, and hopes the lure of the national jersey will be sufficient. The problem is in its application. A huge group of experienced Springboks based overseas have been overlooked this season. The likes of Willie le Roux, Bismarck du Plessis, Ruan Pienaar, JP Pietersen, Francois Steyn, Duane Vermeulen, Francois Louw, and Patrick Lambie were on holiday while their compatriots were nilled by New Zealand.

Francois Hougaard, present that day, was not picked for the autumn, instead returning to Worcester, where he is single-handedly saving them from relegation. Meanwhile, with back-row injuries, head coach Allister Coetzee saw no problem in calling up Bath’s Francois Louw, and then Toulon’s Duane Vermeulen. They are two men who would be pushing for inclusion in a World XV, let alone the Springboks. With such a dire economic position, and a weak domestic league, Coetzee frankly cannot afford to leave out such a wealth of talent.

The final, and most concerning, issue is that of racial quotas. The South African government has set ‘transformation targets’ for various sports, including the aim that 45% of male Springboks will be black South Africans by 2018. In a nation which has seen racism on such a huge scale before, during, and after Apartheid, it is imperative that work continues to promote equality in all walks of life. But quotas are not the answer.

The fact is, an elite team cannot thrive when there is not a wholly merit-based selection policy. The team cannot genuinely be results-driven if they know they haven’t got their best possible team. The very idea of there being criteria other than merit undermines what it means to represent one’s country. Not only does it mean there might be players in the side who others perceive to be undeserving of their place, but it means black players who are there on merit alone may not get the recognition they deserve. The very fact I wondered momentarily whether Warwick Gelant – who made an impressive debut on Saturday – was there solely on merit does him a disservice.

Aside from being patronising, racial quotas serve to reinforce black/white thinking. They create resentment when their aim is to promote togetherness and are, ultimately, arbitrary. The fact women’s rugby has a different target – 80% - shows just how random the numbers are. After all, 90% of the South African population are people of colour.

Picking players because of their race ultimately amounts to positive discrimination, something which is illegal in the UK under the Equality Act 2010, and is against the South African Constitution. By contrast, ‘positive action’ – allowing selection of a black person over a white person if they are equally well-qualified, to promote diversity – is considered lawful. Such a policy should be welcomed by the SARU.

It is often said that it is important for young black people growing up in South Africa to have black role models in the national teams. This may be so, but the effect may be somewhat lessened if these role models ship 57 points against the All Blacks two years running, and lose more often than they win.

It is impossible to tell how much of a direct impact these ‘targets’ are having – in the starting XV against Wales, only three players were not white – but the indirect impact on team morale, and what it means to wear the Springbok jersey, is undeniable.

There is much that needs to be done to improve equality in South Africa, but the issues lie much deeper than the national rugby team. The inequalities are structural, and require a far more nuanced policy throughout society, from the bottom up, to ensure there are equal opportunities for all. If this happened at grassroots level, we wouldn’t be talking about race in the national side, as it would simply reflect the country’s best talent.

For the good of world sport, we must hope it won’t be too long before South Africa is once again a dominant force

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026

Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026 Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026

Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026 News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

![How to Create an Attractive Freelancer Portfolio [5 Tips & Examples]](https://www.varsity.co.uk/images/dyn/ecms/320/180/2026/02/vitaly-gariev-ho2tNOWZYXM-unsplash-scaled.jpg)