What’s on the horizon? Black hole research gains momentum at Cambridge

Dhruv Shenai speaks to students from the Institute of Astronomy about the pioneering research that hopes to deepen our understanding of the universe

It’s an exciting time at the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge. Black holes are some of the most fascinating objects in space, and the department has just appointed an internationally recognised researcher specialising in their imaging.

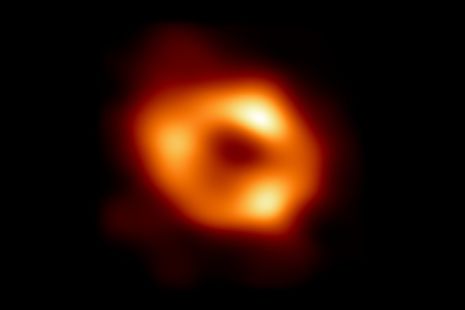

Professor Sera Markoff is a founding member of the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration, whose work captured the world’s attention with the first image of a black hole and its event horizon in 2019. The image quickly entered pop culture, becoming the subject of many memes and news stories. By joining the department, Prof Markoff will be bringing that exciting science and leadership to Cambridge.

Prof Markoff has been appointed the new Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy, one of the oldest professorship titles in Cambridge, whose statutes were drafted by Isaac Newton in the 1700s. To explore the buzz around her appointment, I spoke to two members of the astronomy department at Cambridge who are doing PhD research on black holes.

“I have been fascinated by the results of the EHT ever since I saw that first image of a black hole,” says Stephanie Buttigieg, a PhD student at Christ’s College. “Having Sera in the department is amazing.”

“We cannot only photograph black holes, but almost make movies of them!”

Stephanie’s work focuses on using large cosmological simulations to theoretically model populations of merging supermassive black holes. These black holes, which range from about a million to ten billion times the mass of the Sun, sit at the centres of galaxies and are the kinds of objects observed by the EHT. When galaxies merge, their central black holes are brought together and, after a series of complex physical processes, can eventually merge themselves, producing powerful gravitational waves.

This is slightly different from the niche that Prof Markoff and the EHT investigate. Stephanie explains, “While the EHT observes individual black holes in detail, my work focuses on predicting the collective properties of black hole binaries and mergers across the Universe.”

There’s also a difference in scale. “The EHT zooms in on the immediate surroundings of a single black hole, whereas cosmological simulations [… span] distances many orders of magnitude larger.”

Despite the differences in their research, Stephanie explains that she would love the opportunity to collaborate with Markoff if the opportunity ever arose.

“Black holes are likely to pave the way to a much deeper understanding of our universe”

It was obvious from our chat that Stephanie has integrated into a friendly department. “The Institute of Astronomy is a welcoming and inclusive environment. Each March, the Institute hosts a wide range of initiatives to mark International Women’s Day.” For Stephanie, having women in senior leadership positions across the department is an empowering sign for women interested in science, offering visible role models and challenging outdated stereotypes.

Prof Markoff is the first ever woman to hold the Plumian Professorship, and she’s keen to increase diversity and promote inclusion in the field. “There’s still a stereotype about who does this kind of work, and also a lack of opportunity for many people to study science,” says Prof Markoff. “I consistently strive to improve opportunity and access, particularly for people who don’t have advantages. It’s one of the reasons I wanted to affiliate with Newnham College.”

Richard Dyer is a PhD student from Corpus Christi, also studying black holes at the Institute of Astronomy. His work focuses on the final part of a black hole merger, the ringdown. When the black hole ‘rings down’, it radiates gravitational waves at characteristic frequencies, which can be picked up by observatories like LIGO (which stands for Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory) and (soon) LISA (which stands for the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna). I asked Richard what Markoff’s research could mean for our understanding of black holes.

“I think black holes are likely to pave the way to a much deeper understanding of our universe,” suggests Richard. He differentiates between the black holes we derive from mathematical equations and the ones we observe. With EHT, Richard hopes that we can test whether our theories match our observations of black holes.

In March, the EHT will try, for the first time, to film black holes in action. Richard comments on how big a feat this would be: “We’re living at a time when we cannot only photograph black holes, but almost make movies of them! It’s something that everyone can appreciate, regardless of scientific background.”

Only in the last decade or so have scientists been able to observe black holes in such close detail and with plenty to discover, this makes it the perfect time to be working in the field. Hopefully, the research under the new leadership of Prof Markoff will soon reveal the secrets behind these beautiful celestial bodies.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026