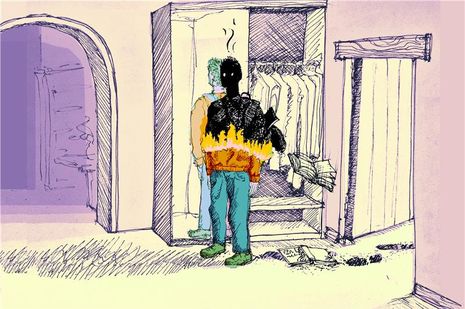

Out of the frying pan and into the fire: the science behind burnout and how to prevent it

Anika Pai explains how you can avoid week five blues this Lent term

Cast your mind back to week eight: you’re lying in bed, most probably ill. It feels almost impossible to drag yourself to the library to finish the final essay of term. The term’s almost done, the end is in sight, yet you simply cannot seem to get it done. It’s a feeling almost every Cambridge student is familiar with – burnout. Hopefully you’ve had a chance to recover over the vacation, but can science help us understand how we can avoid burnout in the first place?

Burnout refers to a state of mental and physical exhaustion caused by exposure to long-term stress. It’s defined by three main components: exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficiency.

Prolonged stress can result in irregular activity in the prefrontal cortex, the region of the brain responsible for attention, memory, reasoning, and decision making. Meanwhile, hyperactivity in the amygdala, another area of the brain, triggers the increased release of the stress hormone cortisol. These responses affect ‘mental energy’, a model representing our capacity for cognitive functioning. Mental energy is finite, and tends to be depleted by our body’s responses to stress. People with burnout spend more energy performing cognitive tasks and need more time to recover from the resulting mental exhaustion. This exhaustion manifests itself as the feelings we find ourselves all too familiar with – fatigue, reduced work efficiency, and cynicism towards work.

“Mental energy is finite, and tends to be depleted by our body’s responses to stress”

Stress also plays an important role in the activity of our immune system. Prolonged stress can result in persistent low-grade inflammation, contributing to chronic pain, gut issues, fatigue, and worsening pre-existing autoimmune conditions or allergies. Sustained cortisol levels may also suppress your immune system, making minor illnesses more frequent and your recovery slower, possibly explaining why you haven’t been able to shake off the freshers’ flu since the beginning of term.

Tendency to burn out stems from a complex combination of internal and external factors. Six major features of work have been identified as risk factors for burnout: unsustainable workloads and limited opportunity for rest, lack of perceived control, insufficient recognition and reward, lack of support, inequality, and conflict between personal values and the work being done. These make it harder for people to find meaning in their work, leading to disillusionment and cynicism.

Personal characteristics, including genetics, health, lifestyle and personality type, govern how an individual responds to prolonged stress. People who are perfectionist, competitive, ambitious with a desire to be in control, traits sometimes associated with having a ‘type A’ personality, are often more likely to burnout.

“Reminding yourself why you chose your degree in the first place can oppose the cynicism that is characteristic of burnout”

The environment someone grew up in also matters. A protective, supportive environment gives individuals a sense of control over their surroundings, and increases purpose, optimism, and tolerance – all traits that are helpful in resisting burnout. By contrast, people who grew up exposed to high levels of social stress show less well-developed coping mechanisms.

Unsurprisingly, the amount of sleep you get affects burnout as well. Insufficient sleep further depletes your energy resources, reducing cognitive capacity, making you more susceptible to burnout. Burnout in turn can make it harder for you to fall asleep due to anxiety and emotional dysregulation, generating a vicious cycle.

So, what can you do about it? Limited research has been done on the effectiveness of strategies to cope with burnout. Studies often involve small groups of participants and very little follow up. Despite this, burnout has been shown to improve following implementation of a variety of strategies.

Re-evaluating your relationship with work can be helpful. The heavy Cambridge workloads can often result in a loss of passion for your subject, but reminding yourself why you chose your degree in the first place can oppose the cynicism that is characteristic of burnout. Engaging in activities outside your tripos, such as returning to the hobby you dropped, attending a society event, or taking a walk outdoors, can be a reminder that your degree isn’t everything.

Alongside this, getting adequate sleep and exercise is crucial for maintaining both physical and mental wellbeing. It can also be beneficial to conserve energy by prioritising more important tasks, while lowering expectations for less critical ones, or skipping them altogether where possible.

Talking to people is also important, demonstrated by the large role that limited social interaction plays in causing burnout. Speaking to a friend could offer comfort, and consider talking to your DoS or supervisor to potentially reduce your workload, or excuse a few badly written essays. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy has been shown to reduce mental strain and improve performance, so talking to a therapist or counsellor could help as well.

One of the most effective remedies, however, is to take a break. This can mean frequent short breaks, such as stepping away from your laptop every once in a while, or a longer break for a complete reset. Take care of yourself, and perhaps (armed with some evidence-based tips) you’ll be able to dodge week 5 blues this term.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026