The origins of writing in the mind

Edward Maher explores the history, origins and cognitive explanations behind humanity’s greatest invention: the written word

In his play Prometheus Bound, Aeschylus has Prometheus bestow upon humankind the gifts of the first fire and then writing. For his pains, the Titan was then famously imprisoned for eternity. In very similar legends, Odin sacrificed his eye to give runes to the Norsemen, Toth gave hieroglyphics to the Egyptians, and Itzmana to the peoples of Mesoamerica. The motif of writing as ‘a divine gift’ appears again and again across global cultures, reminding us that writing is a mystical and feared skill for most of its history, reserved only for a few initiates. This transcendent view of the written word shouldn’t be surprising: the origin of writing represented a great shift in the relationship between thought and language.

It is said that “writing is an instrument of power”, and a glance at its history reveals the truth of this statement. Writing as we know it emerged with the Sumerians and the Egyptians, using simple pictograms to depict financial transactions. This ground-breaking technological innovation facilitated organisation and taxation on a huge scale, and spread rapidly with the first empires of the New East. Our Latin alphabet is descended from that of the Greeks, itself adapted from a right-to-left syllabary used by Phoenician merchants. And yet, at almost the same time, with strikingly similar symbols, priests in modern-day China began carving questions onto bone and turtle shell fragments for divination. The inscriptions range from the profound to the trivial - one inscription from Yinxu reads simply: ‘Will it rain tomorrow?’.

“Literacy was seen as the ultimate step in the evolution of a culture”

So, while the origins of Western writing were decidedly mercantile, the origins of the Chinese script were primarily religious. These two aims have since collided in the modern era, and writing has been carried to every corner of the globe in the Bibles, Qur’ans and Ledgers of missionaries and merchants.

It was at the height of this expansion that serious reflection on writing systems and their psychology began. Literacy was seen as the ultimate step in the evolution of a culture, representing at least one part of the arbitrary standard used to judge societies as primitive (biologically and culturally). Further to this assumption, Western science saw the progression from Sumerian-type logograms to Latin style alphabets as a ‘cognitive inevitability’ in the development of a society. These views are still widely propagated today, with the Chinese writing system frequently described even by professional linguists as ‘underdeveloped’ or ‘ill-suited’.

The psychological origin of writing is, however, far more complex, idiosyncratic, and much more interesting than the reductive ‘East versus West’ dichotomies. When it comes to explaining differences between languages, a new piece of the puzzle comes from the direction of writing. Overwhelmingly, writing systems written in vertical lines are also written from right to left and tend to be syllabic and pictographic (for example, Chinese). The motivation for this remarkable pattern is probably more than just practical (ink smudging isn’t an issue when you’re writing on turtle shells), with its origins probably lying deep in the structure of the human brain.

Recent studies have indeed suggested that reading right-to-left scripts such as Chinese utilises elements of the right hemisphere of the brain, whereas processing of left-to-right scripts exclusively involves the left. This effect isn’t so obvious among children learning to read, in whom a wider range of areas tend to be activated, slowly narrowing down as they hone their reading skills.

How can we explain the sudden transfer in writing direction, which affected Greek in its early existence? Adapting the Phoenician script to the Greek language required a phonemic (letter based) rather than a syllabic (syllable based) system, which is predicted to have triggered a change in the brain regions used to process the information on the page, thus resulting in a shift in writing direction.

“When it comes to explaining differences between languages, a new piece of the puzzle comes from the direction of writing”

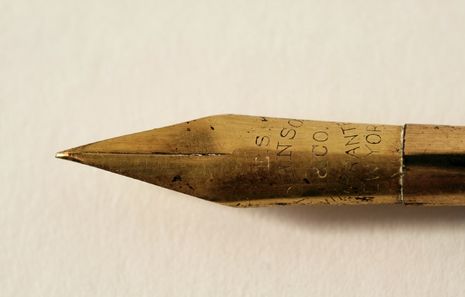

Depictions of ancient writers at work have led some researchers to suggest that ancient writing was a very different cognitive skill than that in the modern day. Processing using only the right hemisphere of the brain, ancient writing involved holding the writing instrument (pen, stylus, etc.) with a claw-like grip, observed among modern-day left-handed children taught to use their right hand. As writing slowly shifted from the right to the left hemispheres, an unusual script emerged - boustrophedon. Meaning as the ox ploughs, it runs in alternating directions, allowing the eye to follow back and forth in a way unattested outside the early Aegean region.

The exact cognitive origins of writing remains a murky and understudied field. However, slipping through the cracks of psychology and anthropology, the study of the ‘ultimate human invention’ and its effects on our brain can shed important information as we head into the next technological revolution. Once again, a technology originating with a few specialist individuals has spread to the masses - but only in future decades will we see the true cognitive effects of this Pandora’s box.

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026

News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026 News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026

News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026 News / Corpus FemSoc no longer named after man6 February 2026

News / Corpus FemSoc no longer named after man6 February 2026