Yawning at the catastrophe: the psychology of climate change

Cambridge University Psychology researchers Dr Sander van der Linden and Dr Cameron Brick speak on whether it is possible to change the behaviour of billions

What is the most effective way to slow down global warming? Some might say robust solutions will have to come from improved technologies – from reliable, clean energy electric cars and more efficient air conditioners. However, Sander van der Linden and Cameron Brick, two researchers at the department of Psychology, argue that the climate change challenge is primarily a social and psychological one: to stop the earth from warming, we need a change of heart.

“Climate change is the largest social dilemma in history,” says van der Linden. The paradox of the health of our planet is such that although at societal level we would all be better off if everybody acted sustainably, at an individual level unsustainable behaviour is typically the default – an easier, less costly and psychologically more attractive choice. If we want to solve climate change, Brick and van der Linden argue, we will first need to understand the psychology of this dilemma: Brick asks, “Why is it that despite all the scientific evidence, people’s general response to climate change is collective inaction?” Public engagement and policy lag far behind the consensus of expert recommendations. So, what is causing people’s apathy?

In the absence of a clear potential villain, there’s nobody to blame except ourselves

“We know from behavioural economics that people care less about things that are far away in the future – a phenomenon called temporal discounting,” says van der Linden. The effects of climate change will be catastrophic, but they are not imminent. Instead, because the processes of global warming are complex, their consequences are delayed. “Even if we doubled our fossil fuel consumption this year, it wouldn’t immediately translate into clear, observable impact," says Brick. We have evolved to run away from predators in the desert, to solve local, experiential and imminent problems – not to be scared of abstract, invisible and delayed threats. In other words, we’re not made for foresight. The very thing that has allowed us to evolve is now coming back to bite us.

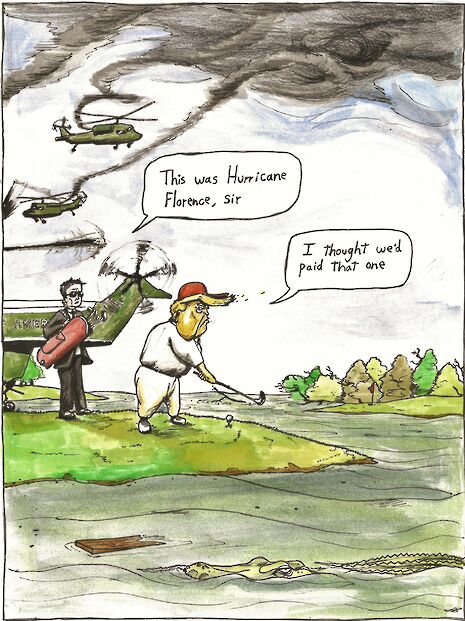

Another problem is that when it comes to climate change, there isn’t a bad guy. “Hardly anyone is walking around deliberately harming the planet,” says van der Linden. Harvard psychologist Dan Gilbert explained this problem as follows: “If climate change was some type of nefarious plot visited upon us by very bad men with moustaches, then I guarantee you that our president would have us fighting a war on warming with or without Congressional approval.” In the absence of a clear potential villain, there’s nobody to blame except ourselves, and this can trigger a range of defensive biases – including inaction.

What needs to happen so that people talk about climate change with their friends and colleagues?

To study the psychology of climate change, van der Linden and Brick employ a range of methods. Surveys assess people’s attitudes to environmentalism, the future of the planet or global warming. More informative than questionnaire data, Sander argues, are experiments: “I like collecting data on people’s behaviour, rather than just what they say, because often those two things are very different.”

But how valid is what people do in a lab when it comes to assessing everyday behaviour? Luckily for psychologists, they also can make use of real-world quasi-experiments. A few years ago, van der Linden and his colleagues studied the effects of a ‘do it in the dark’ campaign at a US college campus, which encouraged students to switch off the light more regularly. “We found that during the campaign people really made an effort to reduce their energy usage, but as soon as the campaign ended, everyone went back to the same patterns of behaviour as they did before,” says van der Linden. Such findings can have important implications for policy: if a government wants to encourage more sustainable behaviour, it needs to know what works in the long run.

One successful environmental policy in the UK has been the plastic bag fee. “It’s amazing how powerful just five pence is,” says Brick, “people really want to avoid paying it.” This suggests that even small financial penalties on other kinds of unsustainable behaviour (such as taking commercial flights, eating meat or driving high-emission cars) might change how people act.

So, is the aim of Brick and van der Linden’s endeavour to turn everyone into Ryanair-boycotting vegans? “I’m getting increasingly pessimistic about changing those types of behaviours,” says Brick. Instead, he is hopeful when it comes to policy engagement. What needs to happen so that people talk about climate change with their friends and colleagues? What does it take for them to write letters to their local MPs?

Only if the public asks for it, Brick argues, will government implement laws and regulations that will slow down global warming. For example, according to recent calculations, replacing the world’s air conditioners with more efficient models would reduce total greenhouse gases by the equivalent of 90bn tonnes of CO2 by 2050 – roughly 30% more than if half of the world’s population were to give up meat. Thus, if the public demanded stricter regulations for air conditioners, it could go a long way to saving the planet.

“Those things are really important and effective, even if the person then goes home and has a giant steak,” says Brick. Nudging people out of their position of comfortable inaction into a feeling of urgency and political agency – maybe that's how we can solve climate change.

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025 News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025

News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025