From A to Zebrafish: what a lab work placement really entails

Despite hundreds of highly competitive summer lab placement programs, Bethan Clark explains the value of taking the time to find out what suits you best

It’s common for NatSci students to undertake a research placement during the summer vacation, particularly in the summer after second year. The expectation is to experience working in a lab environment and exploring a field of research, while familiarising yourself with techniques that can’t be covered in a practical class. There’s a whole range of types of placements. One end of the spectrum is carrying out a research project arranged informally with a lab group, often supported by grants from colleges, departments or societies. At the other exists structured programmes, including research internships and competitions like iGEM. These tend to be fully-funded with highly-competitive application processes.

If you don’t make it on to one of these big programmes, it can be easy to worry about how the experience from a more informal research placement stands in comparison. My experience last summer in a Cambridge lab showed this worry is unfounded, not least because the most valuable lessons are not solely learning new practical techniques, as one might first assume.

I realised the significance of the people one works with and the environment in which one is immersed in a lab

I spent four weeks with the Department of Genetics with the Steventon group in the laboratory of comparative developmental dynamics. For me, the placement was an opportunity to test whether I wanted to continue in academia after my degree. After a surprisingly intense, content-heavy first year of NatSci familiar to many, I was having doubts about my long-held aspirations to work in research. Still, I didn’t want to abandon these ambitions without a proper experience of lab-based research. Given my indecision, committing to applying to big programmes didn’t seem to be the best choice. Instead, I reached out to labs in Cambridge working in development – my favourite aspect of the NatSci course so far.

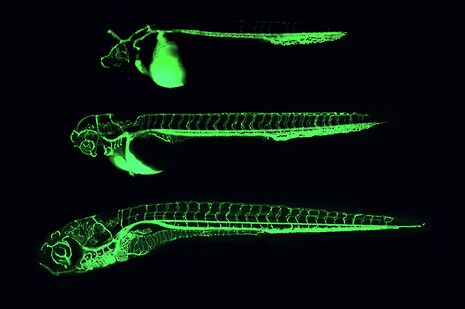

The laboratory of comparative developmental dynamics investigate a population of bipotent cells called NMps in the tailbud of developing zebrafish embryos. As the embryo’s axis elongates, these cells are allocated to one of two different fates: neural or mesodermal. In the lab, I was examining the control of this process by signalling from different factors that NMps encounter as they move through the embryo. Specifically, this involved culturing NMps in a dish and applying inhibitors and over-activators of FGF and Wnt pathways, then quantifying changes in the expression levels of genes that are markers for the neural and mesodermal fates. This was using HCR, a highly specific and quantifiable method of fluorescent in-situ hybridisation. The chance to try my hand at embryo dissection, HCR and advanced imaging techniques was a very valuable opportunity. Having worked with these kinds of protocols later came in handy in my Part II project: even though I was working on a different organism and used different imaging methods, familiarity with the techniques gave me a very useful starting point. On this front, the placement certainly lived up to expectations.

The Steventon group is relatively new and still (rapidly) growing. The size of a group can affect what it’s like to work with, and preference lies with the individual. I found the small group to be a great environment for me. When I was there, the group consisted of only five people: two MPhil students, a PhD student, and a research assistant, as well as Dr Steventon, the principal investigator. From lab tea breaks and end of week pub trips to the general environment in the lab, I realised the significance of the people one works with and the environment in which one is immersed in a lab, in addition to the research itself. It’s vaguer than a list of techniques learnt, yet it’s no less important. In this regard, this research project is probably the most important thing I've done during my degree, because the experience as a whole was so strongly positive. It is no exaggeration to describe this kind of insight into working in a lab as invaluable. I'm now determined to go into scientific research after I graduate.

It’s probably not surprising that my advice is to do a summer research project if you get the chance. If you've just finished Part 1A and are looking ahead to next year, consider factoring it into your summer plans, particularly if you are unsure about research as a career. If you are undertaking any type of research placement this summer, of course use it to test your research interests, but also take the opportunity to explore what type of lab group culture suits you. I’m utterly convinced of the value of summer research projects for these multiple aspects, and I’m very grateful to the whole of the Steventon lab for welcoming, teaching, and guiding me last summer.

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026

News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026 Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026

Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026