The forefront of fish-inspired jewellery

The science of metallics: when nature tries to mimic the awe-inspiring light properties of metallurgy, the result is slightly different

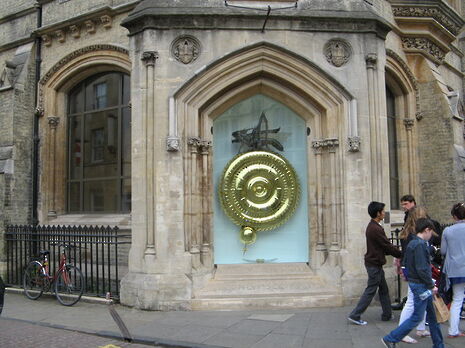

Humans have long been fascinated by the shine of metallic colours. The charm of gold, silver, and other metals is, of course, enforced by their relative rarity and consequent preciousness. Being malleable, metals have been used as currency for centuries, as well as featuring heavily in jewellery and decorations to symbolise power and wealth. While metals may be cast in almost any shape or form, they are also known for their longevity. This is why Cambridge alumnus John C. Taylor chose stainless steel and 24-karat gold for the Corpus Clock (also known as The Chronophage) which he conceived and funded.

The unique shine of metals derives from their electronic structure: unbound electrons are extremely abundant in metals, and thus scatter light very efficiently. As they are not confined in atomic valence shells, they have no associated resonance and thus reflect all colours with high intensity. In fact, light cannot penetrate more than a few hundred nanometers into a metal. The scattering from metals can be fairly random if there are many imperfections in the materials. However, polishing techniques are available to ‘clean’ the surface and make it behave as a mirror.

The distinctive optical appearance of metals cannot be created by a single solid colour, and therefore most paints and coatings with a metal-like shine contain small flakes of actual gold or silver. As such, these are extremely expensive, and so various tricks have been employed to save some money, especially when decorating large surfaces.

One of the most common strategies is to substitute precious metals with less expensive ones. For example, gold may be substituted with aluminium to give a nice yellow shiny appearance. Another trick is to paint something using a standard pigment, and then cover it with a top coat that is transparent and shiny (this is very common in car paints, as well as nail varnish): for instance, silver may be mimicked by having a grey surface covered with a shiny layer. However, when eating a golden cake from Fitzbillies, you can be sure that you are eating real gold, as only few metals have been approved for human consumption.

Computer screens likewise have great difficulty in trying to replicate the shimmery appearance of metals. In fact, silver is simply represented by a tone of grey, and gold by a shade of yellow. Whenever a more accurate depiction is required, the metallic shine is recreated using animations that give the illusion of a mirror-like reflection sliding on top of the surface.

Nature has found a different way to reproduce gold and silver: multilayers. In the outer exoskeleton of some beetle species, one can observe alternating dark, pigmented layers, and light layers which are instead exclusively made of chitin, a long-chain sugar. At each interface between the layers, light of a specific colour is reflected depending on the thickness of the layers. However, because the layer thickness increases as light penetrates deeper, different wavelengths get reflected at different depths, meaning that all colours get reflected, just like a silver mirror. Similarly, silvery fish have disordered multilayers where the thickness varies, but in a less regular fashion. This begs the question: how long until we will be wearing cod-inspired jewellery?

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025 Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025

Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025