Will Brexit make us hungry?

Science Editor Jake Cornwall-Scoones looks at whether Britain can take back control of its food supply

Spam and tinned peaches for dinner anyone? In a country with a globalised food market, such a question should be unthinkable. But a reality akin to this may soon be gracing our dinner plates. A new study suggests that the government is “sleepwalking” into a future of food that lacks both security and safety. I spoke to Erik Millstone, professor of Science Policy at the University of Sussex and one of the authors of this report, to discuss what Brexit could mean for Britain’s food.

Millstone suggests that the government’s approach to the future of food “is like a rabbit caught in the headlights and they don’t know which way to turn,” arguing that Brexit could threaten food security across four dimensions: sufficiency, sustainability, safety and equity.

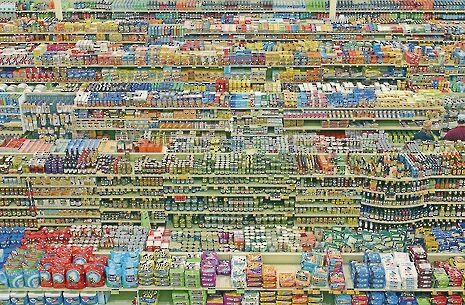

The UK is a country that imports over 50% of its food, of which a large portion comes from the EU. Many have suggested Brexit could lead to barriers to import, with for example the British Retail Consortium noting in a recent report that these barriers could lead to empty shelves. Millstone suggests EU membership instigates a trade-off: “Given agricultural subsidies and the costs arising from that, food prices are on average higher than world food prices, so we are paying a premium. But in exchange for that premium, part of what the Common Agricultural Policy achieves is relative stability in supplies and prices.” Brexit could thus mean a loss of this stability, leaving us “exposed to supply and price volatilities that are characteristic of the world market”.

Subsidies under the Common Agricultural Policy come under two categories: one that takes into account land ownership and area cultivated, and the other in relation to ecosystem services, with the current Brexit plan proposing to restrict all subsidies to the latter. Millstone suggests this plan is dangerous: “I do think that there remains a strong case for production subsidies, because without them, history shows that supplies, and consequently prices, become incredibly volatile, [causing] considerable problems for both farmers and consumers.”

Brexit is also a threat to sustainability, Millstone suggests. “People such as Liam Fox and Owen Patterson and others think that what matters is competition on price and cost, and one of the easiest ways of keeping costs low is by not dealing with issues of the current unsustainability of the agricultural food systems.” These issues are manifold, from extreme levels of greenhouse gas emission, to antibiotic resistance, to the overuse of pesticides and fertilisers, and soil deterioration.

“I’m not sure if it’s a good idea to have the same level of Delhi-belly in Devon, Dunstable or Dundee as in Delhi, actually. No sorry Rees-Mogg that’s not an acceptable level of food safety.”

Professor Erik Millstone

Back in July, Boris Johnson proposed that Brexit would allow Britain to “engage with the world again in a way that we haven’t been able to do for 43 years,” yet this engagement, suggests Millstone, may threaten our very safety. “A free trade agreement with the US would entail allowing into the UK products and processes not deemed acceptably safe in the EU, such as beef produced from cattle into which synthetic growth promoting hormones are implanted.” A different hormone called bovine somatotropin (BST), is injected into dairy cows in the USA to increase milk yields, which in a study of Millstone’s published in Nature, demonstrated increased rates of mastitis and infection of the udder, “so there’s a higher puss content in the milk, and also a high use of antibiotics in the cows, so higher levels of antibiotic residues in their milk.”

Brexit negotiators haven’t just set their sights on the US. With the rapid globalisation of the past decades, many lucrative and expanding markets have opened up, markets with which our government may envisage free-trade deals. Millstone pointed to comments made by Jacob Rees-Mogg at the Treasury Select Committee who said that, “We could say, if it’s good enough in India, it’s good enough for here.” But Millstone didn’t seem too convinced: “I’m not sure if it’s a good idea to have the same level of Delhi-belly in Devon, Dunstable or Dundee as in Delhi, actually. No sorry Rees-Mogg that’s not an acceptable level of food safety.”

The turbulence to Britain’s food caused by Brexit, argues Millstone, could exacerbate the inequity of our already divided nation. “I think prices will rise and the people who will suffer the most will be the poor, and so I think the pressures on them to feed their families with low-cost junk food products, which are high in fat and sugars, will rise, not decline.” Brexit thus becomes as much a public health issue as an economic one. A more equitable Brexit trajectory is not the only solution to this systemic problem. Millstone suggests, “what we need is taxes on not just sugar but other caloric sweeteners and fats,” with this money being “used to subsidise fruit and veg to shift consumption patterns from foods that are unhealthy and are already over-consumed.”

Millstone foresees a short-term future of extreme food insecurity. “The European Union’s insistence is that the UK cannot negotiate trade deals with other countries as long as it remains in the EU. So until the moment of departure the UK is not even allowed under EU rules to engage in such negotiations. And the UK is asking for transition periods and my money says the EU will say, ‘well in that transition period, you can’t start negotiating’ so there’s going to be a big discontinuity at some point.”

Brexit’s effect on Britain’s food is a concern for not only the people of this country but also the multinational conglomerates that dominate the food economy, some of whom back the analysis of Millstone and his colleagues. “There are members of the government who say that ’well the great thing about getting out of the EU is we don’t have to follow all EU rules and Unilever and other companies are saying ‘hang on, unless we follow EU rules we’ll lose access to the European market. We buy from and sell into those markets. We’ve got to stay in the same position.’”

With the continued secrecy over the precise plans of our government as they enter Brexit negotiations, the future of food is up in the air. Given so much at stake, we must hope that the government wakes up from their stupor, recognises the immense challenges at play and deals with them accordingly to procure a future that ensures economic, environmental and public health, benefitting the people, and not jeopardising our basic right to food security

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025