Exhibition: Crawling With Life

Ana Persinaru looks at the exhibition that ‘taps into a 17th-century European mania for collecting, travelling and dissecting’

As you walk in, go through the Impressionist room, then down the Renaissance corridor, past the Old Dutch masters and you’re there. Tucked away in the Shiba room is the latest Fitzwilliam Museum exhibition on botanical art, a small space that possibly befits the generally dismissive view of this particular genre. The works are rather misleading in their apparent banality and unassuming nature - no pun intended - compared to the oil canvases of the Jan Brueghel father and son duo but the story the exhibits tell, collectively, is one of adventure.

Disclaimer: there are very few introductory words as you step into the Crawling with Life exhibition, and quite disappointingly the curators have not made an overarching link between the works that would reveal some secret or other of the artistic genius. I would say that the exhibition taps into a 17th-century European mania for collecting, travelling and dissecting (see also: The Anatomy Lesson by Rembrandt). Most paintings and etchings on display were done by North-European artists, which goes to show the importance of colonialism for the development of the botanical illustration genre, as well as the growing trade links between continents as some of the etchings were done after the importation of exotic flowers from distant countries began.

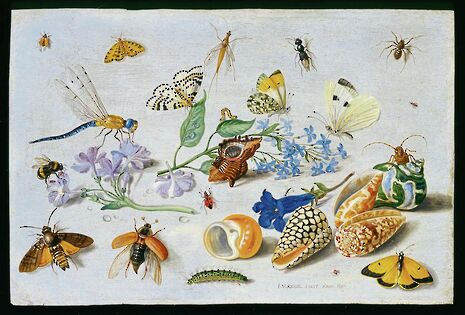

Prized possessions, these works feature minute detailing and vibrant pigments. Jan van Huysum’s busy vase compositions are just what you’d expect to find in Dutch art of the time: a plant encyclopaedia’s worth of different flowers, glistening water droplets and insects galore, most of them outlined or even entirely painted with a single-haired brush. Refreshingly organic, the works in Crawling with Life lack the suffocating veneer of their more valuable contemporaries, having usually been painted on vellum or a fibrose type of paper with watercolour, befitting their subject matter and showing signs of their venerable age in the form of crumples and smudges where the artist’s hand rested in the process.

Much like a #nature Instagram post, the works have a varying degree of verisimilitude; Thomas Robins the Younger stands out due to his attempt at a faded landscape in the background of a frangipani flower being circled by a butterfly while Wenceslaus Hollar’s prints are decidedly scientific and two-dimensional. Walking around, you get the sense that the painters are trying to be artistically virtuous as well as true to a subject matter that can often be imperfect due to its natural creator. An example of this is the carnivorous plants which were of particular interest to botanical illustrators for obvious reasons. Georg Dionysius Ehret’s “textbook perfect” drawings focus on these beautifully disguised traps whose apparent beauty gives no clue of their trickery. It really is like an allegorical representation of the century’s obsession with fatal attraction or tragic death, featuring in many novels or works of art of the 1700s and 1800s and of pretty much every century ever since, meaning that the botanical illustrations are still very relevant today.

If history, love and death haven’t so far tickled your fancy, feminism must. The genre was largely seen as the only acceptable mainstream form of art with which women could engage liberally, which is why almost half of the exhibits were created by women.

Viewpoints can differ; some see this as an oppression of the female artist, bound to slave over microscopic detail that no-one would notice while others regard the attention to detail and graceful execution by a woman’s hand as superior to their male equivalent - just one close inspection of Barbara Dietzsch’s textural tour de force is enough to prove that.

Although probably not the highlight of the Fitzwilliam Museum’s calendar, Crawling with Life is nonetheless a great introduction to a popular genre of the 17th century and the way it so artistically discloses nature’s secrets. Did I forget to mention the huge taxidermic butterfly and beetle?!

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026

News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026 Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026

Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026 News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026

News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026