Theatre: Antony and Cleopatra

Heather Williams gives a triumphal welcome to Cambridge American Stage Tour’s returning show

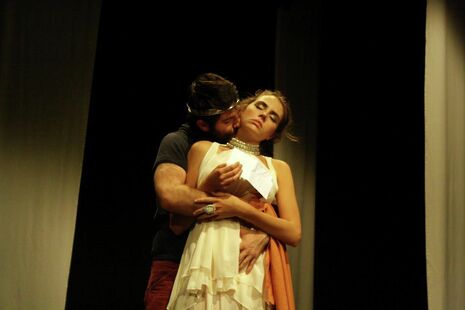

It is easy to be enthusiastic about Shakespeare, but I can’t really be enthusiastic enough about this specific production. From its first moments it is spellbinding: Mark Antony and Cleopatra, played respectively by Tom England and Genevieve Gaunt, open the play with a heavily erotic moment, folded in each others arms, then pursue each other along the theatre aisles, with their disembodied laughter the perfect counterpoint to the unimpressed glances of their assembled followers.

Performances were universally strong. Ellie Nunn made a hilarious Charmian, perfectly treading the balance between comedy and tragedy in response to the changes in her mistress’s fortunes. She has some really good moves with a knife. Gaunt was mesmerising as Cleopatra, exploiting the femme-fatale stereotype of her character to create moments of sheer feminine whimsy, moments of chilling psychosis, and then moving beyond to a performance full of depth and genuinely moving agony. England was at his best when he was at his most restrained - at times his Antony strayed a little too far into a caricature of male bravado/stupidity, with a chin always raised comically too high – but later this disappeared, replaced with a sensitive rendition of a man stuck between a rock and a hard place. The ensemble cast did everything right.

There were some absolutely lovely surreal and cinematic moments. When Mark Antony reads the letter containing the news of his wife’s death the lights go down and he stands there, lost in thought, as the other cast members creep up behind him and levitate glowing cubes above and around his head, as if to suggest the ghost now departed. Soon after, Alex Gomar’s Enobarbus attempts to engage him in speech, and the audience hears what Antony must be hearing – little fragments of congratulations pierced by lost audio as Gomar stops himself midway through a word or a sound yet keeps his mouth moving.

I’ve rarely seen slicker physical theatre. Swords and armour were replaced by suggestion, with the male cast members relinquishing their weapons for coloured scarves. As a visual metaphor, these made explicit Cleopatra’s disarming of Antony and his men and the move from combat to inactivity. In later scenes they served to make the soldiers ridiculous, as Antony and Caesar flapped ineffectually at each other in an orgy of violent futility, a metonymic dance for their political situation. Actual combat was beautiful and inventive and everybody was super-hench after what I imagine must have been a fairly gruelling month on the American tour from which it has returned. Sometimes attempts at slow-mo wore a little thin, but were ultimately undermined by some self-deprecating, comedic little twitch from Jack Mosedale in one of his many roles. Usually having him just standing there was enough to lift a scene.

Hanging drapes formed the set for the greater part of the show: the simplicity of these forced you to recognise the sheer complexity of the lighting design, which was emotionally in tune with just about everything. The production designer, Fiona Berreby, deserves much respect for not trying to create a really decadent, crowded picture of the Egyptian court and Roman army, opting instead for a Fellini-esque use of black space (I’m thinking Satyricon) punctuated by weird glowing objects and long chains of luminescent hieroglyphs.

All in all, this was pretty flawless. Eerily professional, even. Something definitely worth extricating yourself from the beginning of term chaos/fresher’s week in order to go see.

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025

Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025 News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025

News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025