Film: Man With a Movie Camera

Taking a trip back to 1920s film-making, Jessica Donnithorne reviews Dziga Vertov’s experimental classic from a modern-day perspective

For a film with no story, no sets and no actors, Man with a Movie Camera (1929) is a surprisingly entertaining cinematic experience. Its fast-paced, playful use of avant-garde cinematographic techniques and rhythmic editing create an in-depth exploration of modern civilisation that never ceases to amuse.

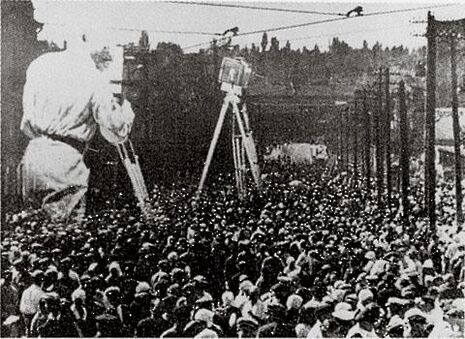

Russian director Dziga Vertov’s camera is omnipresent, documenting a day in the life of Soviet citizens in an urban environment. We see them work, play, undress, beg, wash, cry and laugh from dawn through to nightfall. As a mechanical eye onto the world, there is a tangible sense of the endless possibilities of the camera, still a fairly novel device. Vertov is undoubtedly pointing to the potential power of film – he superimposes an enlarged, giant version of himself and his hand-held camera teetering over a crowded street of protestors. He is not without a sense of humour either, placing a shrunken version himself and his camera into a mug of beer. His experimentation with double exposure, slow and fast motion, split screens, dolly shots, jump cuts (to mention but a few of his techniques) are visually delightful, even to a modern viewer accustomed to sophisticated cinematography. Vertov’s quest, the subtitles inform us, is to create ‘an authentically international absolute language of cinema’, a language which can harness the potential of the camera to document and transform modern civilisation on Marxist principals.

As a silent film, it has had countless different soundtracks attached to it from Irish post-rock, to Ukrainian guitar, to French piano and Norwegian electronic jazz. The Arts Picturehouse opted for Michel Nyman’s 2002 score which accompanies the BFI’s DVD version of the film, a powerful and emotive accompaniment. As a pioneering work in the development of the documentary - art film buffs, this is not one to miss.

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025

Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025