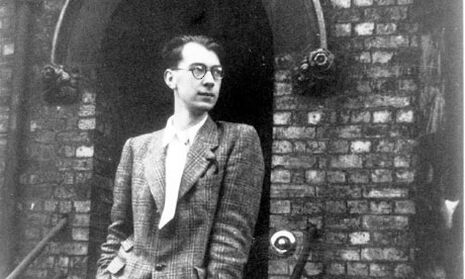

Literature: Philip Larkin – Poems selected by Martin Amis

This week our literature critic Patrick Mayer gives his view on the new collection

One wonders whether a new edition of Larkin’s poems is really necessary. Not only is the entirety of his work still in print (and how many dead poets can boast of still having their poems published in their original volumes as well as in a Collected Poems?) but a surplus of material concerning his life, love and letters is on the shelves and swelling by the year. Add to this the fact that Larkin is probably the most loved and celebrated of English poets after the Second World War, and it becomes obvious that the virtue of this particular release lies not in the selection but the selector.

Martin Amis has some claim to a unique perspective on his subject; his father was, in his own words, Larkin’s most "rousing correspondent", not to mention a kindred spirit, and his own childhood was peppered with visits from this "distinctively solitary" individual.Whether this amounts to any genuine appreciative insight into the work is debatable, but what light Amis sheds on Larkin’s life, and the aspects of the work those details of the life illuminate, are of interest. The introduction contains some revealing anecdotes (mostly culled from Amis’s memoir) that characterise Larkin the Man: one describes a dinner with Larkin and Monica Jones, the poet’s most significant lover, during which Larkin behaved "like the long-suffering nephew of an uncontrollably eccentric aunt".

A "paedophobe and skinflint", "near-nihilistic", "self-starved" – these are just a few of the epithets Amis employs to describe Larkin’s personality, and with some justification he cites poems such as ‘Money’ and ‘Love Again’ to demonstrate the way in which Larkin "siphoned all of his energy…out of the life and into the work". For Amis, Larkin embodies the Yeatsian principle of perfection of the work rather than perfection of the life, but this rather sanctimonious appraisal of another man’s existence (as if such a thing could be quantified) seems rich coming from one whose own life has been the cause of so much scandal. When discussing the backlash that occurred after the publication of Anthony Thwaite’s Letters and Andrew Motion’s Life, Amis proudly trumpets his belief that "writers’ private lives don’t matter", a somewhat hypocritical turn considering the extent to which his introduction relies on biographical details.

By far the most interesting claim Amis makes for Larkin is that he be considered not only as a people’s poet, but as a novelist’s poet, for he is a "scene-setting phrasemaker of the first echelon". This is very true, and by defining Larkin in such terms Amis draws attention to a relatively unsung achievement of his work, a gift for narrative painting and scenic description that’s best exemplified by longer poems like ‘Show Saturday’ and ‘The Whitsun Weddings’.

Amis is capable of pinning down exactly what it is in Larkin’s work that admirers find so captivating: who else uses an essentially conversational idiom to achieve such a variety of emotional effects? Who else takes us, and takes us so often, from sunlit levity to mellifluous gloom? The most insightful remark Amis makes on the process of reading Larkin is the sense that "his greatest stanzas, for all their unexpectedness, make you feel that a part of your mind was already prepared to receive them – was anxiously awaiting them"; this is something I believe most Larkin lovers would rapidly assent to.

As far as the selection goes, Amis’s taste is fairly conventional, and Larkin’s oeuvre is small enough to render most sizeable selections from it virtually identical; all the favourites from the published collections are here, as well as the best of the uncollected poems. Amis declares that Larkin’s four volumes of verse are "logarithmic", that they get "stronger and stronger by a factor of ten", and his choice reflects this, although I’m sure many readers would actually rate The Whitsun Weddings as a stronger collection than its successor. This is where the partiality of personal selections becomes a distinct problem, and at £14.99 it would seem wrong not to buy the Collected Poems instead.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025

News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025