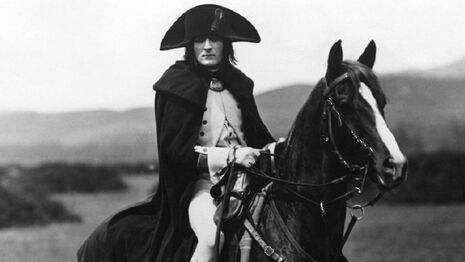

Close-Up: Napoleon

Abel Gance’s 1927 film feels just as innovative today it must have 90 years ago, finds Jacob Osborne

One of the main highlights of my Christmas break, somewhat unexpectedly, was watching a five-and-a-half hour silent film at the cinema. While I have never seen a film anywhere near that long, I have also seen little that can compare with the monumental ambition of the film itself – Abel Gance’s 1927 epic, Napoleon.

“The real thrill of the film is the matching of its grand storytelling with an incredibly innovative visual style”

Intended to be the first of several depicting the life of Napoleon Bonaparte, the film takes us from the general’s youth to his Italian campaigns of the 1790s. The tone is consistently heroic. Napoleon champions the French nation, his tactical brilliance present in every situation. Albert Dieudonné’s performance as the general conveys a compelling force of will and stolidity in the face of misfortune. Because the narrative stops so early in his career, we miss crucial events which challenge this apparent heroism, the most conspicuous being his disastrous 1812 Russian invasion, which directly led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of French soldiers in horrendous, below-freezing conditions.

But despite a lack of ambiguity in its interpretation, the film is far more than a tribute to Napoleon’s triumphs. Rather, it is an exposition of the triumphs of Abel Gance in constructing a true epic. An enormous supporting cast portrays Napoleon’s family and figures from French history, including the revolution (Gance has a cameo as Saint-Just). There are battle scenes with seemingly thousands of extras. But the real thrill of the film is the matching of its grand storytelling with an incredibly innovative visual style. This is partly manifested in the energy of the cinematography. An early scene at a French military school, where the youthful Napoleon directs a snowball fight as if it were a battle, is excitingly shot like an actual war film, with fast cutting and multiple camera setups.

Gance also goes beyond the mostly static camera setups of his contemporaries, strapping his camera to everything from overhead wires to the back of a horse. In a highly avant-garde move, many shots are handheld . At a rumbustious party, the handheld camera becomes a dancer, jerking around writhing female bodies in dizzying fashion. In a stormy battle, it becomes a mud-spattered foot-soldier, frantically dodging gunfire and submerged corpses. This scene, which lasts for an hour, vividly encapsulates the visceral horror of war in a way that seriously rivals Saving Private Ryan.

The most celebrated innovation is the finale. Widescreen was almost non-existent at the time of filming, and most of the film is shot in the much narrower aspect ratio of 1.33:1. But during the final twenty minutes, which depict Napoleon’s Italian campaigns, the screen suddenly widens to reveal a mesmerising triptych. In order to achieve a ‘widescreen’ effect, Gance operates three cameras side-by-side. There is a huge amount to take in. Sometimes the three images align to form an impressive landscape; at other times they show different aspects of the same scene. It’s genuinely and profoundly rousing – a delight given the present ubiquity of widescreen film and television.

As late as the 1950s, Napoleon existed only in incomplete versions, some of which lacked as much as two-thirds of the running time. Inspired by an early viewing experience, British historian Kevin Brownlow has led an ongoing project to restore the film; it is now almost totally complete. It was recently re-released alongside a new recording of Carl Davis’ brilliantly dynamic score. Napoleon is therefore not only Gance’s triumph, but that of Brownlow, Davis, and all those who have cherished silent cinema enough to revive this extraordinary experience. It’s quite simply a masterpiece, and easily one of the greatest experiences I’ve ever had at the cinema.

News / Deborah Prentice overtaken as highest-paid Russell Group VC2 February 2026

News / Deborah Prentice overtaken as highest-paid Russell Group VC2 February 2026 Fashion / A guide to Cambridge’s second-hand scene2 February 2026

Fashion / A guide to Cambridge’s second-hand scene2 February 2026 News / Downing Bar dodges college takeover31 January 2026

News / Downing Bar dodges college takeover31 January 2026 Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026 Lifestyle / Which Cambridge eatery are you?1 February 2026

Lifestyle / Which Cambridge eatery are you?1 February 2026