COVID-1984?

Erin Gerrity argues that we cannot simply turn a blind eye to the potential danger that the pandemic restrictions pose to our democratic freedoms.

With the UK’s daily coronavirus infection rates consistently surpassing 50,000 cases and death tolls sadly skyrocketing, the announcement of a third national lockdown did not come as a surprise to most people.

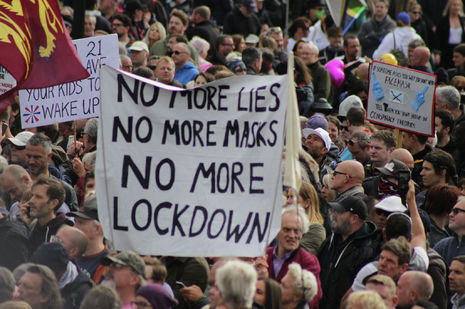

Lockdown 3.0 means a return of the stay at home order. When the first measures of this kind were introduced last March, headlines were hit with images of covid-sceptics at protests, demanding haircuts and claiming “fear is the real virus!” In spite of how ridiculous these stories seem, it is important to recognise that the pandemic has raised valid concerns about the level of control that governments are able to exercise.

Here in England, the law prohibited 18 million people from celebrating Christmas with their loved ones. It is currently illegal to let anyone enter your household or to leave it for non-essential reasons. Neighbours are calling the police on one another to report restriction breaches.

“It is crucial at present that we protect the NHS, save lives and reduce infection rates so that restrictions can be lifted once again.”

Undoubtedly, it is crucial at present that we protect the NHS, save lives and reduce infection rates so that restrictions can be lifted once again – but it is also important to discuss the dangers associated with the implementation of highly restrictive measures upon the public.

The emergency powers granted to the government in the Coronavirus Act 2020 are not without precedent. They follow in the footsteps of the Defence of the Realm Act 1914 and the Emergency Powers (Defence) Act 1939, both of which authorised the government to do whatever it believed necessary to win the world wars.

We can find interesting parallels between the public attitude to restrictive measures during the pandemic and during wartime. Initially, the need for enhanced security and control over areas vital to the war effort was supported but, as the war went on, the public became increasingly frustrated by the more trivial rules, such as limited pub opening times and strength of drinks on offer. It appears that we may be facing a similar situation today.

During our first national lockdown, there was a very cohesive, British sense of ‘getting through it together’; complete compliance with restrictive measures was reported to be as high as 69%. As the pandemic progressed, however, there seemed to be an increasing discontent with the heavy restrictions being enforced, as well as exasperation with the rules that seemed inconsequential, such as one hour of exercise per day or the 10pm curfew on pubs and restaurants. By the end of the second lockdown, there had been a drop in complete compliance with lockdown measures to as low as 46%.

“The government must strike a crucial balance between the implementation of strict regulations and the protection of the basic, personal freedoms of the public.”

Now, as we are confronted with a third imposition, the government must strike a crucial balance between the implementation of strict regulations to reduce infection rates and the protection of the basic, personal freedoms of the public. It is important for the government to remember that success in reducing infection rates depends on public cooperation. It appears that thus far this may have been taken for granted. The UK government’s approach to enforcement has been rather laissez-faire; quarantine following travel and isolation following contact with an infected person have always been self-implemented. What’s more is the government has consistently put in place measures that they have no intention of enforcing, like the rule restricting us to only dining out at restaurants with members of our household – how were restaurants expected to enforce this?

Our relaxed enforcement approach is in stark contrast with a number of countries at the opposite end of the political spectrum, like autocratic China. China has claimed great victory in its handling of the pandemic, having used strict measures to maintain low infection rates. The restrictive measures introduced by democratic leaders across the globe may have been more effective at curbing infection rates if they had been implemented in a more authoritarian manner, as they were in New Zealand with rapid closing of borders and mandatory “managed isolation” in hotels.

The coronavirus pandemic has triggered debates about whether a correlation exists between political regime and efficacy of pandemic management, with particular concerns being raised for fragile democracies. Last April, sixteen member states of the European Union released a diplomatic statement stating their concerns about the risk of violations to democracy and fundamental freedoms during the pandemic. Despite the risk to countries led by unstable democratic governments being quickly recognised, a study published in December by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) reported that around 60% of countries across the world have introduced measures during the pandemic that “infringe on democratic principles”.

Although the threat to democracy in the UK is low, it is essential to acknowledge the potentially dangerous precedent that we have set in passing our coronavirus legislation with so little scrutiny; the Coronavirus Act 2020 was fast-tracked through parliament in just four sitting days. The extent of the additional power that this act gives the government may surprise the few that take the time to research them. For instance, the act permits the extension of time limits for the retention of fingerprints and DNA samples. Most of this legislation only ceases to be valid after two years – a significant period of time – and the continued operation of the act is only available for review every six months.

Despite UK citizens being in the fortunate position of relative safety from true infringements upon their human rights (no, your right to a haircut doesn’t count), it is essential to be aware of and discuss the valid concerns about the extra powers given to the government. We must acknowledge the limits this places on freedom, so that we can protect our own liberties and that of people living in countries with less stable governments.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025