For less privileged students, the UK education system is rigged against language learning

Language education in the UK is inadequate and caters especially poorly for those from a less privileged background, argues Elizabeth Haigh

No one can dispute that the UK has a shocking record when it comes to learning languages. Yet in a time where political uncertainty is making the study of foreign languages even more important, the rates of pupils taking them is plummeting, with the number of pupils sitting GCSE French dropping by 63% and German by 67% since 2000.

Many students see languages as a hard subject, and low demand combined with the underfunding of schools is leading to many dropping classes in some languages all together. But it is not as simple as a subject popularity contest. The reality is that for less privileged students, the system is rigged against them, offering no real encouragement or opportunities to use foreign language skills.

Opportunities to help our language skills are often limited for poorer students, with support varying widely from college to college

During my first year at Cambridge, I, like many other students, was plagued by a constant sense of imposter syndrome. Having taken French A-Level, I decided to study languages at university in part out of defiance. Coming from a low-income household, almost all my holidays had been in the UK and I did not know anyone, apart from my teachers at school, who could speak more than one language: English.

Arriving at university, I was already looking forward to my year abroad, and eager to start ab initio German, having never even visited a German-speaking country when I applied. But I soon began to struggle upon realising that many of those around me were not only much more fluent than me (many having learnt languages from a much younger age), but they had been able to spend extended holidays, or even lived, abroad. This was extremely intimidating, both from a language skills point of view and a cultural one.

In speaking to other students from less privileged backgrounds, I know that I was not alone in this feeling. And even having arrived at Cambridge, opportunities to help our language skills are still often limited for poorer students, with support varying widely from college to college.

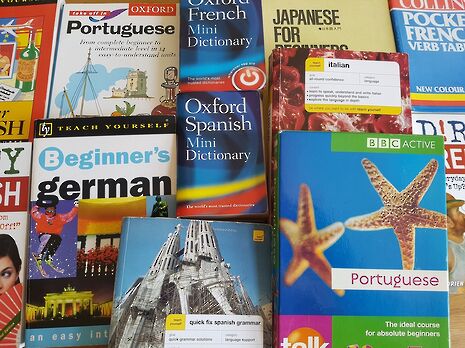

In no way do I wish to blame people for taking full advantage of the ability to travel abroad. Inspiring a love of languages in your children is something all parents should seek to do, and what better way than to show them the amazing experiences other countries have to offer? But in the UK, sadly, learning languages comes with a price tag. Of course, anyone can pick up a book and learn the basics, but we are simply behind much of the world in the way we teach our young people.

Who is encouraging those who do not have these opportunities?

It is easy to understand why languages are seen as difficult. Many students stumble into their first language class aged 11, while we have been learning Maths, English and Science since we were 4. Language learning is completely different to any other kind of learning, taking lots of time and effort, with no real end; you can never complete a language in the same way as you can finish reading a book. The fact that language learning first appears so late in the UK curriculum is a travesty.

Students suddenly have to find a whole new approach to studying, at a time when GCSE and A-Level pressure is already looming. In addition, for poorer students who do not have have the opportunity to travel or go on expensive school trips, it can seem like a pointless exercise for which they will never see the results of their efforts. Why bother to learn Spanish if you have no foreseeable opportunity to go to such a country?

According to the European Commission, in 2016 over 80% of working-age EU adults with a tertiary education reported knowing at least one foreign language. In the UK, only 34.6% of adults aged 25-64 reported that they knew more than one foreign language. The simple truth is that we are stuck in a cycle of monolingualism, where people do not question why foreign languages are necessary, and therefore do not encourage others to learn them.

We should be inspiring everyone, but in particular young people, to study languages. We should be teaching basic skills at a much younger age, as is done in many countries around the world, rather than offering students just 2 or 3 years of classes before allowing them to opt out.

Almost everyone I have met during my year abroad so far has been able to speak at least some English, plus other languages. I find myself imagining if they were to come and visit where I live, a small town in rural Shropshire. If they spoke no English, how many adults would be able to help them? How many would even know what language they were speaking? I can assure you that the answer is barely any.

If students have the chances and opportunities to learn languages through trips abroad, private instruction, even private education, then they should be encouraged. But who is encouraging those who do not have these opportunities? My family often joke that they have no idea where I get my language skills from. But this is precisely the problem. We as a country need to change how we view languages and offer everyone equal access to opportunities. Until we do this, languages are in danger of becoming a subject for the elite.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026

News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026