Privilege is about so much more than if you paid school fees or not

Just because you didn’t go to a school with a 400 year history and a cricket pitch, it doesn’t mean you’re not privileged

Private schools are a Bad Thing. Any reasonable person admits it. Everyone knows 7% of children are educated at fee-paying institutions, yet they dominate ‘the establishment’, making up nearly 40% of the Cambridge undergraduate population. But our fixation on notorious private schools, with their nice blazers and mummies in Range Rovers, distracts from the huge disparities in the quality of education within comprehensive schools. What postcode you live in, what your parents do, how much they earn, and the priority they place on education (read: how much they will punish you if you don’t do your DT homework), matters every bit as much as if you went to the comp or to a school founded by Royal Charter sometime before 1400.

Children on free school meals are 27% less likely to achieve five or more GCSEs at grades A*-C including English and maths. Half of all free school meal children are educated in just a fifth of all schools. Deprivation and poor educational attainment is highly concentrated, and deceptively hidden. Cambridge may be a middle-class fiefdom, but so too are the good comps from which it draws many of its students. There are mainly middle class schools, and then there are mainly working-class and ethnic-minority schools. Both are officially part of the ‘comprehensive’ system, but there is little comprehensive about it: the term stifles the debate on variation between schools.

“Whether you are privileged or not is about a lot more than whether you paid school fees”

Government decisions have exacerbated the problem. The introduction of league tables for comprehensive schools by the Major government in 1992 meant that headteachers’ emphasis was focussed on beating other schools, not nurturing and developing their own pupils. Under Tony Blair, we were warned there would be “no hiding place” for schools that were not striving to improve. League tables might have had positive effects: they may have been the first step on the road to recognise variation within the school system. Diane Reay, Cambridge’s Professor of Education, told The Guardian, “because the schools that working-class children mostly go to are not doing well in the league tables, there’s a lot of pressure on their teachers and heads to increase their league table position. That means they focus ruthlessly on reading, writing and arithmetic.” Working-class kids may do alright in maths, because without it you really are screwed. But education is about so much more than that: good comprehensives have the bandwidth for art, for music, for PE, because they can afford it, or their parents can pay for clubs, or the kids are being tutored at home, meaning they pick things up quicker in class.

The Conservatives’ ideological addiction to free schools and academies has wrenched money from comprehensives. Reay commented that “masses of money has gone into the academy and free school programme, and it’s been taken out of the comprehensive school system.” Reay discovered that free schools receive 60% more funding per pupil than local authority primaries and secondaries. The Tories moved £96m intended for improving underperforming schools to academies. The problem is getting worse: primary schools with high numbers of working-class pupils are expected to lose £578 per pupil because of government cuts.

Let’s say you are a family looking for a school to send your eleven-year-old to in Potters Bar, a town in Hertfordshire just outside London. The school where everyone wants to go is Dame Alice Owen’s, which brags of 96% of GCSE students securing 5 A*-C grades. The situation is made particularly tricky because the catchment area of Owen’s extends all the way south into Islington, but only into a tiny bit of suburban Potters Bar. Owen’s received 21 Oxbridge offers in 2017. The second choice for most people is Chancellor’s School, which receives 70% of its GCSE pupils achieving 5 A*-C grades. The bottom of the pile is Mount Grace. Mount Grace is known as ‘Mount Disgrace’ by local children, such is the shame in attending it. Families who know how to work the system, who can afford to fund accruements like violin tuition or rugby training are more likely to be successful in the school race. People get rightly het up about grammar schools institutionalising education inequality, but aren’t these disparities in the comprehensive system having precisely the same effect?

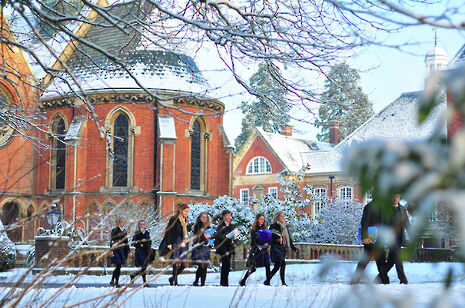

We have a system where children who are born in the same ward of the same hospital and educated in the same ‘comprehensive’ school system have wildly different chances in life. The media are obsessed with stale stereotypes of where power and wealth have their seat: articles on ‘elitism’ and education privilege are illustrated with images of Eton, Harrow and Westminster. The conversation about what a good school, education and student mean is too narrow. This article hasn’t even taken into account the complex social hierarchies which exist within schools themselves: everything from the state of your uniform to having the space at home for a desk speaks eloquently of your class and chances. Many students at Cambridge have had these disadvantages, and have overcome them through hard work. This should be celebrated, but we need to have a more candid discussion about why they had to be overcome in the first place. Whether you are privileged or not is about a lot more than whether you paid school fees

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025