Tomi Reichental: ‘Although we are talking about the past, it’s happening again’

The Holocaust survivor speaks about why he decided to dedicate the last years of his life to sharing his horrific experience

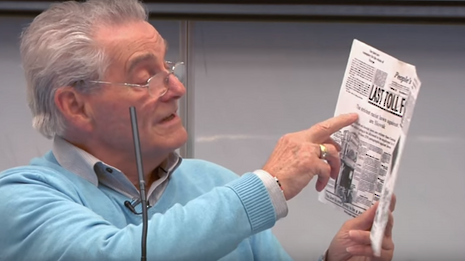

For 50 years Tomi Reichental did not talk about the horrors he witnessed during the Holocaust. But now, speaking at the Cambridge Union at the end of Easter Term, he says, “they can’t stop me!” Born in 1935 to Jewish parents in what was then Czechoslovakia, Tomi has found his vocation in providing a living face for the Holocaust, a historical event existing for most of us only in half-remembered classroom textbooks.

Time has eroded any reluctance he once had about attempting to describe what must feel like the indescribable. But I detect that a sense of duty has also played a part. A quote with which he has a strong affinity is William Faulkner’s aphorism: “the past is not dead. The past is not even the past”. As he explains: “the meaning is that, unfortunately, although we are talking about the past, it’s happening again. My latest documentary is basically about what is happening today with the refugees, and of course the name is Condemned to Remember, which says it all, because in the late 1930s when the Jewish people wanted to escape from the Nazis nobody wanted them. And now, just two or three days ago, we had that instance with the refugee boat – the Italians didn’t want them; the Maltese didn’t want them... it’s the same as was happening in the 30s. There was a huge ship taken by Jewish people from Germany and which nobody would take in. Eventually the ship returned and most of the passengers perished in the Holocaust.”

“In the next 15 to 20 years there will be no more Holocaust survivors left and the deniers will have a free hand to say that it didn’t even happen. I hope the people that I talk to never forget”

He speaks of the disturbing results of a recent survey conducted in America which revealed that up to 40% of the country’s youth are not aware of the extent of the atrocities committed in Nazi concentration camps. It is this sort of collective short-term memory that motivated him to travel to over 500 schools in Ireland alone, speaking to over 100,000 students about his experiences. “In the next 15 to 20 years there will be no more Holocaust survivors left and the deniers will have a free hand to say that it didn’t even happen. I hope the people that I talk to never forget.”

Speaking to Tomi, I can’t help recalling the scary instances of myopia in the 21st century: the denialism of David Irving, or the contemporary Slokavian far-right espousing the ideology of the very same regime that handed Tomi’s extended family over to the Nazis. Tomi feels very strongly that the reluctance of European governments to accept refugees is a dangerous recapitulation of past wrongs. Yet, he explains, he has found many young people extremely responsive.

“In Condemned to Remember, I was speaking to a German girl and I broke down in a terrible state because she told me that she would remember what I spoke about. People who see the film ask me why I broke down at that. It was because those were the words I wanted to hear, especially from a German girl. When I speak in Ireland and say that ‘we must not forget’... there is no connection for an Irish person. But the whole thing happened in Germany and it is up to the Germans to carry the memory, and this girl was telling me this, and it touched me so much because that’s what I wanted to hear. If we don’t keep the memory, it is going to get forgotten.”

“I asked students what they knew about the Holocaust and they said that six million Jews perished... That’s all they knew.”

Much has been written about the nature of evil and the correct way to apportion blame for the Holocaust. For Tomi, it is “both difficult and easy” to define evil and good. One of his other documentaries, Close to Evil, centres around his attempts to establish contact with former SS guard Hilde Michnia in an attempt to heal historic wounds. Famously, Michnia continues to deny the extent of the atrocities committed at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

“She was evil. And she’s still evil, because even today she’s not able to admit that what they did was wrong. My family asked why I wanted to meet this woman, who is such an evil person. It’s because I think that she was a victim of her time. And I wonder what I would have done if I had been born into that environment. These people were fed lies and they were brainwashed to believe that what they were doing was right.” But for Tomi this does not absolve perpetrators of evil. “If things like this happen, the people who commit them should be able to judge if it’s right or wrong. When they were accused after the war they said ‘we only carried out orders. If we didn’t do it, they would have killed us’. But in reality, if a soldier was in the Einsatzgruppen, and they said: ‘I can’t do it’, they would probably have been transferred to a different unit. They wouldn’t have been killed. So, they could have said ‘no’. But their excuse was that they had to do it because they were only carrying out orders... A person should distinguish between what is evil and what is good.”

Tomi never gets tired of telling his story, although he admits he is asked the same questions hundreds of times over. “I started to talk about it 14 years ago... I saw that in schools they learned about the Second World War, and within this they were taught about the Holocaust. When I started to speak I asked students what they knew about the Holocaust and they said that six million Jews perished. That’s all they knew.”

It may be too superficial to claim that 2018 resembles the Europe of Tomi’s childhood. But his warning that we need to understand the past at more than simply surface level resonates in an era where the factual basis of our information is notoriously uncertain. Which is why, after concluding that he is very lucky to have photographs by which to remember his family, he believes he owes it to their memory to continue to reach as wide an audience as possible, for as long as he is able.

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025 News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025

News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025