Revealed: Sick students failed by University guidance

Varsity investigation finds intermitting Cantabs are still banned from the city, despite years of campaigning

A Varsity investigation has revealed serious problems with the intermissions process, despite years of student campaigning on the issue. Archaic and unclear guidance from the University, inconsistent treatment when intermitting and returning, and mishandling of mental health issues were all raised as concerns by the students Varsity spoke to, with the President of Student Minds Cambridge (SMC) calling out colleges’ “distrustful nature” towards “troubled” students. The investigation found:

- Inadequate understanding of mental health issues by some senior staff.

- Archaic and unclear guidance on rules, including banning intermitting students from the city.

- Many returning students felt they had a lack of support.

- Total numbers are increasing, with disparities between genders, colleges and subjects.

Intermission, which involves students skipping terms, or often the whole academic year, is almost always aimed at helping students overcome serious issues, medical or otherwise. However, of the many students who contacted Varsity, all had experienced mental health issues, some alongside physical ailments, with many reporting that applying for intermission had worsened their condition.

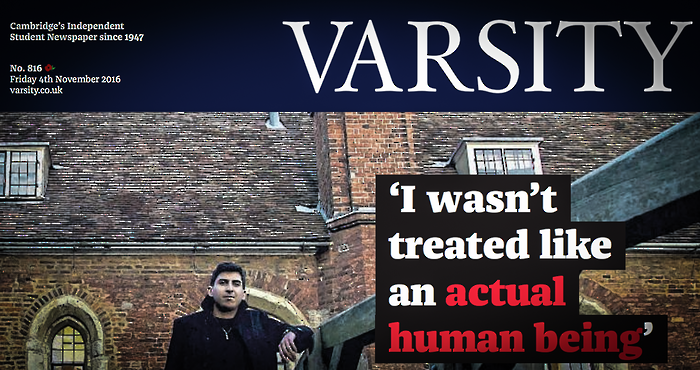

It is the colleges which are largely responsible for intermitting. While some students reported feeling supported through the process, others endured delays, during which their condition worsened, as well as suspicion from senior staff. One student told Varsity: “at no point did they treat me as an actual human being.”

Disparities between colleges also translated into markedly different rates of intermission. Between 2010 and 2016, the non-mature college with the highest rate, Girton, intermitted almost double the proportion of students as Corpus Christi, which had the lowest rate. This may reflect different attitudes towards granting intermission, with some students reporting reluctance from their senior tutors and others being pressured into the process.

Disparities in the treatment of students were also apparent between faculties. One postgraduate student said that his department lacked the “basic knowledge” that “mental health and physical health are not the same,” suggesting that they treated his severe anxiety “much like after one breaks an arm”. While departments are not directly involved in intermission, data nonetheless showed significant gaps between Triposes, with Psychological and Behavioural Sciences students almost five times as likely to intermit as Engineers.

The total number of intermissions also appears to be rising, albeit with some fluctuations. Between 2010 and 2016, the total number of students intermitting rose from 195 to 250, with rises observed in four of the six years. Sophie Buck, the CUSU and GU Welfare and Rights Officer, put the rise down to “greater acceptance of intermission as an option and stigma reducing campaigns”, including ‘Degrading is Degrading’ in 2011. However, a University spokesperson noted that “data fluctuates year on year”, and warned that the small numbers available “do not provide sound evidence of patterns”.

For many students, attaining permission to intermit was the first of a number of challenges they faced. Once intermitted, a number of complex regulations come into force for students, who are required to sign an agreement as part of the process. They are routinely barred from entering colleges and University buildings, and most were advised not to visit Cambridge at all. Students reported feeling confused by the rules, and cut off from their friends. One student even reported being barred from their college’s June Event, despite non-University guests being otherwise permitted.

Responding to Varsity’s investigation, the University stated: “it is important that students use their time away from their studies to focus on the cause of their intermission (often recovering from illness) and that this is not disrupted.”

However, SMC President Keir Murison strongly criticised current intermission procedures, telling Varsity that the group “condemn[s] the practice”. Murison noted that, although leaving Cambridge and returning home is “useful” for some students, for others “going home is not an option if their life there is not healthy”. The University pointed out that the Disability Resource Centre (DRC) remains available to students during intermission.

The most difficult stage for the students Varsity spoke to was their return. In a 2016 investigation, Cambridge was the only one of the 30 universities contacted by The Guardian which required some students to sit an exam, as well as submit medical evidence proving that they had recovered, in order to return.

A University spokesperson said that it was “rare for an intermitting student to be required to take an academic assessment as a condition of returning”, and that this would only be the case if it “would provide reassurance to both the student and their College that the student is in a strong position to resume their studies”.

Buck suggested that such exams were “effectively discrimination” against disabled students, requiring them “to get into Cambridge twice”, the stress of which could hinder their recovery. Moreover, she said that “intermitting students do not have the adequate resources to prepare for these exams,” alluding to the ban on entering University facilities.

While some students reported feeling they had a strong support network upon their return to college, the overwhelming majority reported feeling socially and academically disadvantaged, with one saying that joining a new cohort of students “can make you feel like an outsider even after you return to study”.

Many returning students reported unclear or absent information. One Natural Scientist at Clare, whose request to return in Michaelmas was rejected because they had intermitted in Lent, told Varsity: “a lot more could have been done by college to make sure I was rehabilitated correctly so I wouldn’t have to struggle with both academic and social demands.”

Another reported that the University had not replied to their completed application to return until one day before term started.

Indeed, one student at Selwyn, who found they had to start their new course in its second year, reported finding the transition “incredibly stressful”, and that they were now feeling “totally overwhelmed”. The student has since dropped out entirely.

Data showed 228 students never returned from intermission over the six-year period examined, out of a total of 1,301.

Investigating Intermissions

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026