How The Communards changed the course of queer history

The Communards are under appreciated, given their cultural contribution to queer liberation, says Daniel Kamaluddin

In the busyness of university life, save the presence of pride flags briefly blessing the flag masts of select colleges, it’s important to remember that February is LGBTQ+ History Month. And as much as the fight for liberation still has a long path to run, it is perhaps still more difficult to imagine a time when the right to love was contested both through state oppression, the stigmatising, disastrous handling of the AIDS epidemic, and individual acts of violence.

That said, when The Communards, composed of Jimmy Somerville and Richard Coles (now of television comedy and murder mystery fame), burst onto the British music scene forty years ago, queer liberation was still fledgling. There was no state recognition for same-sex couples, a different age of consent for homosexuals, and even the people who were above 21 were still regularly punished because of loopholes in the 1967 Sexual Offences Act - the single piece of legislation which offered any protection of queer rights. The whole state and cultural apparatus of the United Kingdom was so heteronormative that the Thatcher government had yet to dream up Section 28, which prohibited ‘the promotion of homosexuality’ by local authorities in the same year as The Communards broke up, 1988.

“The whole state and cultural apparatus of the United Kingdom was so heteronormative that the Thatcher government had yet to dream up Section 28”.

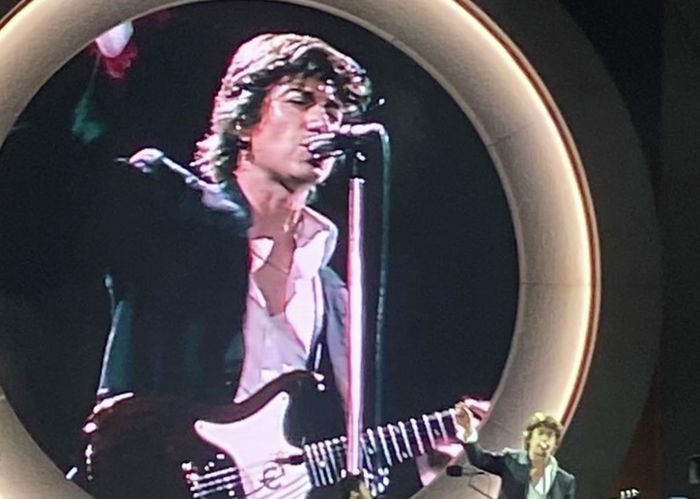

The Communards are one of those rare bands that can make a serious claim to having altered the music scene and national culture they emerged into. Jimmy Somerville, the duo’s lead singer, had left his previous band, Bronski Beat, which had just been invited to join Madonna on tour at the height of her fame, because he felt it was increasingly becoming captured by corporate, big-money music interests. The band had departed from its original goal of capturing the difficult reality of the queer lived experience in the UK in the 1980s, in tracks like Somerville’s most celebrated song: ‘Smalltown Boy’, which captures the agony of leaving one’s family and community behind to find liberation in the city. Somerville wanted to do something different, something radical; to trade press popularity for lyrical and aesthetic honesty.

To start, in the midst of the Cold War, the band wrapped themselves not-at-all discreetly in the trappings of Soviet aesthetics. Their name, too, carried Marxist undertones, a reference to the proletarian commune which took over Paris in 1871, and inspired the writings of Marx and Engels. If this wasn’t subversive enough, their music was, from the start, founded on the desire to contort genre and resist classification. Coles was a classically trained pianist, while Somerville took his cues from the glory days of disco. Put together, what is produced is an extraordinary universe of sound with all the potential to contain the joyful, elegiac and angry in a single album, and sometimes even a single song.

Rarely has a single band managed to be so much, and that’s before one even considers its cultural and political impact. Many queer artists in the period attempted to assimilate with society’s normative expectations; Elton John, for example, addressed many of his love songs to women, and refrained from using male pronouns; his songs that ae addressed to men are de-sexualised. Other performers in the period transform their queerness into a brand, a spectacle, rather than a lived experience, like Culture Club.

The Communards, by contrast, were unapologetically queer; there was no adaptation of pronouns, no compromise with the political status quo. ‘Don’t Leave Me This Way’, their cover of the Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes original, which spent four weeks at number one in the charts, does not limit its celebration of queerness merely to sexuality but also to gender. The higher voice in the track is Somerville’s soaring counter-tenor, and the lower voice is Sarah Jane Morris’ earthy alto. However, when lip-syncing live on Top of the Pops, they switched voice parts, highlighting the fluidity of gender roles.

“They embraced a radical conception of queerness, one where the struggle for liberation is not merely limited to gay rights, but bound up with the struggle against classism and racism”.

They embraced a radical conception of queerness, one where the struggle for liberation is not merely limited to gay rights, but bound up with the struggle against classism and racism. ‘Reprise’, for example, is ironically dedicated to Margaret Thatcher, but is in fact an excoriating criticism of the soullessness of Thatcher’s neoliberal project, and the human tragedy it created.

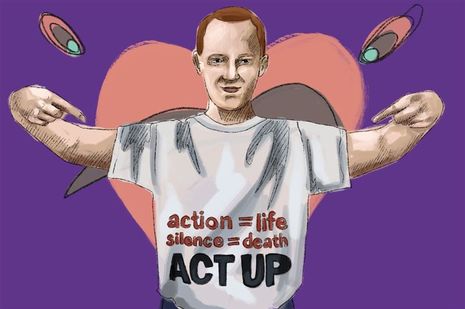

For me, their most beautiful and devastating track is ‘For a Friend’, which was for a long time my favourite song in the world. The song is dedicated to the memory of Mark Ashton, Somerville’s closest, ‘best friend’, who tragically died from AIDS at the age of just 26 years. Somerville’s voice sounds distant, far away, half-angel, half-mourner. His falsetto sounds like weeping. The sense of loss is so intense that it feels like ‘watching the world fade away’. All Somerville wants is to ‘kiss’ his friend ‘once goodbye’. It leaves me with shivers every time.

More than anything else, The Communards’ music sounds exceptionally good, it makes me genuinely sad that they are not more widely listened to. Their tracks are so kaleidoscopic; their influence so broad that it is hard to pin them down in a single article. I don’t feel that I have even begun to do them justice. All I ask is that you consider giving them a listen and learning a little more about their contribution to queer history.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026