‘It’s entirely possible that we get it wrong’: what do archivists actually do?

Isadora Vargas Mafort speaks to Kevin Roberts, archivist at the University Library, about the profession’s daily surprises

Are archivists historical hoarders? When picturing a wide and long room stuffed to the brim with old manuscripts, it may be easy to see the profession as such. Yet when I sat down with Kevin Roberts, the archivist at the University Library, he quickly raised the stakes of archival work – framing it with a sense of emergency that leaves no time for gathering dust. Our conversation paints a new picture of the typical archivist: passionate, pragmatic, and great in a crisis.

Our discussion begins with the assertion that archives are not about locking things away, but protecting them and keeping them available. “The whole point of the archive,” Roberts tells me, “is that you’re saving the material to make it accessible. There’s no point in keeping the stuff if nobody’s ever going to see it.”

Roberts hadn’t considered the profession when completing his undergraduate degree in history, but fell into it when looking for a job in Birmingham. His first project as an archivist involved looking at records of the Barrow Cadbury Trust archive – records of “Cadbury’s of chocolate fame”. He found “it was just fascinating. I loved it from the start.”

“There’s no point in keeping the stuff if nobody’s ever going to see it”

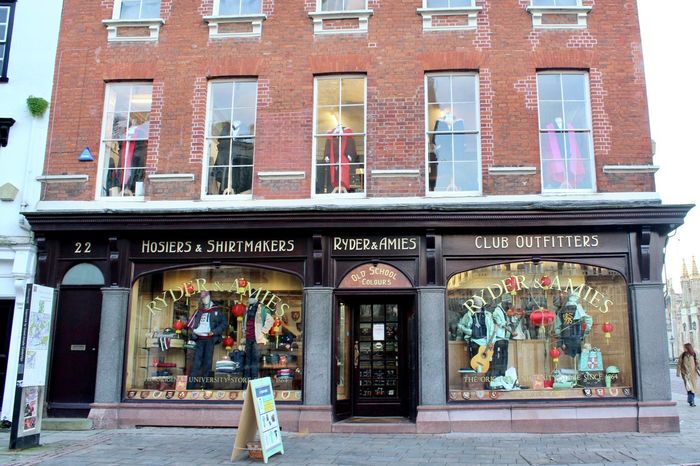

The Cambridge archives also store the developing and final words of big names in history, which serve as reminders of the role the institution has played in global discovery. There are records of world-shaking genius, such as the writings of Newton, Darwin, or Herbert Kretzmer, who wrote the English lyrics of Les Miserables.

For anybody who adores stories, archives can also be a place of constant entertainment, especially with the “absolutely absurd” records of human folly. Kevin tells me about one of his favourite manuscripts, getting the story out through a series of amused, reflective chuckles. “I think it was an officer in the East India Company who must have had some time on his hands,” he explains, who’d drawn “what looked like a British cavalryman on a barrel wearing riding boots, powered by gas.” The idea, Roberts gathered, was: “you could mass produce these and move armies from ships onto the shore. It’s absolutely crazy.”

Archival work looks different every day. Sometimes it entails examining whether incoming material “relates to other material we’ve got and fits within our collecting policy”. Often, it involves searching for and finding “a lot of stuff that will end up in the skip,” and is “under threat of imminent destruction”. The archivists see value in what’s been thrown aside and allow that to be “permanently preserved” in the case of future research. “Of course,” he tells me, “it’s entirely possible that we get it wrong.”

The archivists cherish these manuscripts, viewing them as “potentially in need of a home,” and the team sometimes goes to serious lengths to rescue them. With a look of fond recollection and pride, Roberts shares the conditions he has withstood when visiting homes in search of material. “Hopefully they have heat,” he tells me, “though I have crawled around some places in wintertime when there was none.” There are, however, clearly no regrets: “The building was going to be sold in three weeks,” he continues, “it was an emergency.”

“History is always in the making”

The desire to preserve and document is seen in our everyday lives. The urge to look back through scraps of the past is present whenever you scroll through your camera roll. The impossibility of keeping it all documented emerges when the notification pops up that your storage is full. We struggle to archive our own lives everyday, so imagine how overwhelming it must be to sift and sort through the lives of people, institutions, and nations day-in, day-out.

A difficult aspect of the job, Roberts shares, is “the knowledge that you’re never going to know it all. You could live for a thousand years. You wouldn’t even touch it.” Our conversation colours the profession with a sense of constant discovery – the records may stand still in their preservation, but the stories that emerge from them are endless. “There are so many amazing things that we don’t even know exist,” he continues. “Sometimes, nobody has looked at one particular item and read one particular line”.

Seeing Roberts’ excitement as he speaks of documents he discovers – from 2016 marriage records to descriptions of James Cook’s voyages –I find myself wondering how interesting the daily records of our lives might become in the future.

“Every organisation will create records. Just think how many emails you send off in the course of a day. You generate loads of records, there’s probably going to be maybe 2%, 3% that would actually be of long-term historical importance.” History is always in the making. The question remains: what will eventually find its way into the archives?

More than anything, the work of an archivist is to appreciate and facilitate the understanding of human change and development through time. There’s an empathy, it seems, towards the profession: a respect for what’s left over from people’s lives, and an enduring excitement to revisit them.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026