‘The sense that art really matters’: On Kettle’s Yard’s role in Cambridge with Andrew Nairne

‘Every design decision has been determined by your existing audience’: Kettle’s Yard director Andrew Nairne speaks with Akshata Kapoor about the past and current exhibits

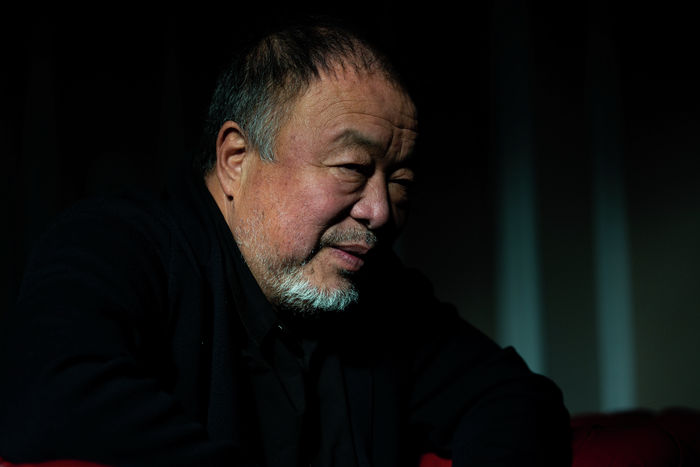

On the morning of the press viewing for Kettle’s Yard’s newest exhibition, The Liberty of Doubt by Ai Weiwei, I spoke with Kettle’s Yard director Andrew Nairne. Despite the bustle of the press, Nairne made time to sit down in perhaps the only remaining quiet corner of the gallery to talk to me about Kettle’s Yard’s exhibits and the move to decolonise museums.

The last exhibition I saw at Kettle’s Yard was Sutapa Biswas’ Lumen. Both Ai and Biswas’ exhibitions were uniquely crafted, clearly curated through careful consideration and collaboration. I began by asking Nairne what goes behind a curation of an exhibit.

“I hope that Kettle’s Yard, the Fitzwilliam, [...] can do more to reflect the actual world”

“Well, we have the Kettle’s Yard House collection, which is a unique collection of art in a domestic setting of the house of Jim and Helen Ede. Then the galleries originally opened, very small, in 1970. Since then, every curator has tried to think: ‘How do we show the living artists in these galleries that in some way reflects the spirit of what interested Jim Ede?’ That is,” they reflect, “the sense that art really matters, it enriches people’s lives. He was keen that people tried in whatever they could to live with art – we have a student loan collection and students every year borrow print editions and put them on their bicycles and cycle off for their colleges. That has had an incredible impact, of not just having a poster on your wall but having an actual artwork.”

“[We want to show] artists who have something really worth saying. It’s fair to say we’ve always had a diverse program, and even more so now. How can we, through our exhibitions, reflect a multiplicity of experiences and identities among our student population?”

“We’re also showing that our sense of home, which links to the idea of the Kettle’s Yard house, is very split. A couple of years ago we showed Oscar Murillo who was born in Colombia and lives in London. Where is his home? The show coming up is Howardena Pindell, [who] is a Black American artist in her 80s. Her work is an extraordinary combination of very beautiful abstract paintings and anti-racist films.”

“Cambridge University does not have a good track record in terms of diversity. It is getting better – it is accelerating. I hope that Kettle’s Yard, the Fitzwilliam, in dialogue prompted by students, can do more to reflect the actual world and the kind of breadth of who our audiences might be.”

“Weiwei’s interest in ancient Chinese artefacts is also part of a reclamation of history”

I have been thinking about the various connections of the recent exhibitions to history and politics, migration and race. I ask Nairne about how modern art is in dialogue with history. Nairne considers the ways in which history can be considered to be “reclaimed” by modern art: “[I think] it was David Olusoga, a prominent speaker around decolonisation, talking about Black history in the UK. One of the things he points out is that, in a way, this isn’t new history. This is just how history should operate. You know, when one may say ‘new histories’ you’re sort of implying somehow the previous history was just totally static. But [Olusoga] would argue that this history should be a living, changing force.” Nairne sees artworks by artists from diverse backgrounds as a way to showcase and preserve a living history. “I suppose the question is which stories, which bits of history, are visible and prominent, and which bits aren’t?”

“Ai Weiwei, when we first met him on Zoom, spent half an hour talking about the importance of memory and history in China because of the Chinese Communist Party. A lot of the time, the [CCP] want to eradicate history. So Weiwei’s interest in ancient Chinese artefacts is also part of a reclamation of history. In the case of Sutapa Biswas, she was born in India. It’s ... her art.” Nairne pauses with a sense of nostalgia, laughing: “I love this exhibition, but I’m also missing the last one. Her art is somehow poetic, imaginative, but also very powerful. A kind of reflection on her own background, on the racism that she has personally suffered. I think for her again, history is really important.”

Beyond the gallery’s unmistakable connections to the house and ideas it sprung from, the innovative layouts and curation of multimedia installations in recent exhibits move away from traditional museum layouts that house artefacts behind big glass walls. I am interested in the idea of decolonising the museum as a space, looking at how we access museums and move around exhibitions and interact with what’s on display.

“In terms of Kettle’s Yard, we like to think we’re open to everybody. It’s an automatic door, we’ve got welcoming staff, we do training. But there are things to do. I was thinking more generally about cultural places: every design decision, like the carpet as you go into theatre, the chairs, food, all of it, without you really knowing if you’re the manager, has been determined by your existing audience. That existing audience being white, middle class, educated. So, if you recognise that everything you see has been designed [like this], then how do you break out of it? How do you sort of turn it upside down? And the answer has to be almost putting a mirror. You walk into Kettle’s Yard, there’s a mirror straight ahead. We would want to say in the future: if you say who are you to Kettle’s Yard, we will go we’re you. That will be a kind of ideal.”

“Everywhere has a way to go. We work very closely with communities in North Cambridge – we have for seven years. Cambridge is a very unequal city. We’d like to work with students more. We really hope we can be a really important open space for conversations, for dialogue, for discussions for these kinds of issues.”

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025

News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025