“Viruses don’t respect borders”: Joseph Nye on the Global Reset

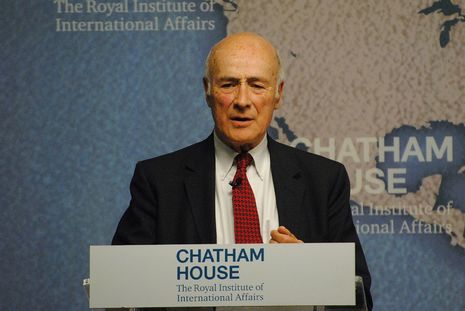

Alex Parton talks to American political scientist Joseph Nye about the Sino-Western conflict, a Biden presidency and what not to do when fighting a pandemic

From chairing the National Security Council at the height of the Cold War to managing intelligence under Bill Clinton, you would be hard pressed to find someone more familiar with the ins and outs of the US administration than American political scientist, Joseph Nye. And yet, sitting down with Nye after a panel discussion at the union on Sino-Western relations, I am struck by how relaxed his manner is. Even when discussing the prospect of a new Cold War, he barely falters in his stride. This is a man, after all, who has seen and done it all. His theories of neoliberalism and soft power have defined the direction of several US presidencies, from Clinton to Obama, and his ethos can be felt around the world even to this day.

The prospect Nye sees himself facing is one exemplified by the Thucydides Trap. The theory, popularised by his Harvard colleague, Graham Allison, suggests that, when an emerging power threatens to displace a dominant power, the end result is almost always war. With Washington and Beijing increasingly at odds in what appears to be an ever-escalating series of confrontations, each vying for global supremacy, the question will be whether this “Thucydides Trap” is avoidable.

The picture Nye paints of the status quo is somewhat bleak. He looks out upon a stormy sky, where “liberal ideologies of human rights and multilateralism have gone on the defensive”, where “America has gone from a benevolent hegemon to an aggressive party”. The Covid-19 pandemic has failed to deliver as the great equaliser, it has in fact merely accelerated pre-existent trends, exemplified by a “decline in economic globalisation, an increase in authoritarian politics, and worsening US-China relations.”

The situation is particularly acute for secondary powers like the UK who find themselves caught in the middle. He points to how China and the US have both used a combination of hard and soft power to achieve their aims, utilising trade, investment and expanding influence through geo-economic projects of infrastructure. But it is unlikely such projects can continue. “The Belt and Road Initiative (China’s large-scale global development strategy involving infrastructure investments around the world) will be scaled back as both China and the US face reduced resource capabilities and domestic unrest,” Nye suggests. He highlights Trump’s refusal to release funding for the WHO as the latest example of this increasing “economic nationalism”; no longer will secondary powers be able to play a hedging approach between the US and the PRC.

"The Covid-19 pandemic has failed to deliver as the great equaliser, it has in fact merely accelerated pre-existent trends, exemplified by a “decline in economic globalisation, an increase in authoritarian politics, and worsening US-China relations.”"

Since the late 1990s, countries such as the UK have been able to avoid picking sides primarily due to the perceived delinking of superpower security and economics. Countries could pursue relatively autonomous policies of development, allowing Italy to join the Belt and Road, just as the UK joined the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank in 2015. A similar example was brought to light during the Cambridge Union panel: Cambridge academic Dr Kun-Chin Lin asked audiences to carefully monitor the unfolding events in Hong Kong. Where London financiers once stepped in to snap up capital drain from Russia in the 50s and 60s, secondary powers like the UK will have to be aware more than ever of the cost of going against a superpower’s wishes. As Lin summated: “superpowers will have less to give and more to demand in return”.

And yet, Nye insists, such a current state of affairs seems to be entirely of our own making. Much of the blame for our lack of cohesion falls at the feet of Xi Jinping and Donald Trump. Both reacted to the virus not by informing and educating but by denying, delaying and blaming, stalling an effective unified global strategy. Here Nye refuses to pull punches. Of the 14 presidents he surveyed in his recent book, Do Morals Matter? Presidents and Foreign Policy from FDR to Trump, “Trump is the most amoral and has done the most damage to American soft power”. Leaders like Trump are lazy, they “reinforce the status quo”, “tapping into pre-existent divisions to generate support.”

A true leader, Nye claims, would have quickly recognised some basic facts: that “viruses don’t respect borders”, and that “neither country can solve these problems acting alone”, championing “power with others rather than power over others”. Trump and Xi could have called for an emergency G20 summit or met with the UN Security Council to organise effective multilateral systems for international cooperation. Instead, the opportunity was squandered.

Nevertheless, amidst the gloom Nye sees opportunity for redemption. One of the greatest geopolitical tragedies of the Covid-19 pandemic has been the wasted opportunity for Sino-Western reconciliation. Nye sees the solution to the belligerent escalation of current Sino-Western relations to be grounded in restoring mutual trust, uniting over common interest and transnational enemies like Coronavirus and climate change.

Such a phenomenon is not unheard of. After September 2001, Beijing and Washington came together to counter Al-Qaeda, and after the 2008 crash the two worked side-by-side again. Nye calls for bold proposals from the US and China to finance a new issue of the IMF’s global reserve currency, to undertake cooperative economic measures alongside debt relief for emerging and developing economies. He implores superpowers to take a lesson from history, calling for a revitalised “moral leadership”, a “major Marshall plan for an international Covid response”.

To avoid this calamitous race to the bottom, the US will need strong leadership under a uniting figure. It is here Nye explores domestic issues that will come to define how the coming years will play. Will a Biden presidency revise its stance on China, seeking new ways of dealing with the superpower? Or has the damage already been done, drawing the US into the inevitability of conflict with the PRC? He smiles slightly at this. “I’ve been talking to people involved in the campaign” he admits, betraying his permeation into the US political fabric. “In the rhetoric of the election campaign you can expect a hard-line from both sides”, but “the people who surround Biden have very different views than those around Trump”. He insists the American people still ultimately want a “moral foreign policy” in line with a Wilsonian tradition, prioritising conceptions of identity over ethnicity, championing liberalising political, cultural and economic freedom.

"He implores superpowers to take a lesson from history, calling for a revitalised “moral leadership”, a “major Marshall plan for an international Covid response”."

Nye insists “it’s not whether you follow your national interests, rather how you define your national interests” that countries should be concerned with. Trump’s ‘America First’ epitomises the narrow approach that will damage the world in the fight against the pandemic. Instead, countries should look to a “moral foreign policy” that strengthens the international institutions around the world. Indeed, some transnational organisations seem to be moving in the right direction. Recent developments have seen Nye far less worried about the unity of the EU than before. He is genuinely impressed by the agreement between Macron and Merkel to bridge the divide between northern and southern EU states and admires their willingness to “step up in defending international organisations such as the WHO”. As we look to the future, he recognises neutrality to be near impossible but hopes the EU can utilise their power effectively, “revising and revitalising the WTO” and strengthening our collective global leadership.

In a globalised world, the landscape of future conflict has been drastically altered. In place of the bloc on bloc rivalry of the Cold War, we are experiencing the divergence and decentralisation of the material basis for power. As Nye observes, “networks are the key source of power”. This is power found in restructured global value chains and altered forms of transport, logistics and digital finance. By exercising “prudence in managing the great power rivalry” and championing “cooperation in managing new transnational threats”, the US and China must recognise that broadening their national interests into empowering others can help them accomplish their own goals.

With Mike Pompeo, US Secretary of State, recently calling for Britain to take a side and NATO secretary-general, Jens Stoltenberg, calling for Western countries to “stand together” against Chinese influence, the wartime rhetoric seems to be mounting. But the universal challenges we face as a species are only increasing. As Nye rightly points out, it is worth remembering that the second wave of the 1918 influenza outbreak killed far more than the first and, should Covid-19 rear its head again, the world must be prepared. The Covid-19 pandemic crisis is only the first of many transnational issues our interconnected world will face. China and the US currently produce 40% of the greenhouse gases and the next global battle humanity will face will be against a far more unforgiving adversary. Neither country will be able to combat this threat to national security alone and, as the two largest economies on earth, for better or worse the US and China must resign themselves to a relationship of cooperation and competition before it’s too late.

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025