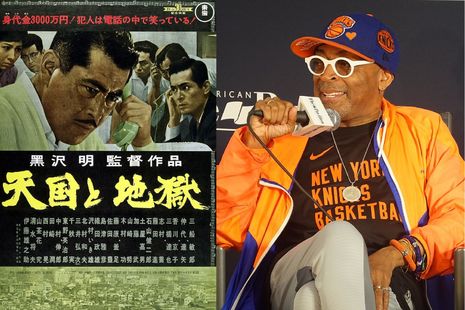

The politics of Highest 2 Lowest

Aaron Tan revisits Kurosawa’s classic in the wake of Spike Lee’s anticipated remake

Much is dissatisfying about Highest 2 Lowest, director Spike Lee’s re-interpretation of Akira Kurosawa’s 1963 masterpiece High and Low, and his first feature-length ‘joint’ in five years. Plenty will rightfully complain about an intrusive, often sub-par background score, some wooden acting, and bold editorial choices that sometimes fail to hit the mark. Nonetheless, by the time the credits roll, all is forgiven. With all its jagged edges, discordant notes and earnest awkwardness, Spike Lee has made a rich, ambitious film that is entirely his own – not something to take for granted in today’s big-budget landscape. Nonetheless, technical quibbles aside, Lee’s formal idiosyncrasy also manifests as an ideological shift from Kurosawa’s original scorching class critique. It’s a move that could have been simply reactionary, but actually also renders his reinterpretation a fascinatingly reflexive lens on the relationship between art and capital.

Both films open on the same beats: a business mogul (Toshiro Mifune in 1963 and Denzel Washington in 2025, both fiery, outstanding performances) receives a phone call from a kidnapper who claims to be holding his son’s life hostage. The kidnapper demands a huge ransom which, if paid, could jeopardize a risky business deal and bankrupt Mifune/Washington. The kidnapper has made a mistake, however, and has instead taken the son of the businessman’s chauffeur. The question of whether the businessman will do what is right, and sacrifice his fortune, occupies the first half of both films.

“Lee’s camera, as its title suggests, is less concerned with offering a systematic view than tracing an action-packed journey between these two poles”

Hereafter, the films diverge drastically. Kurosawa pans down from the glitzy penthouse in which this personal drama takes place into the streets of Tokyo. Toshiro Mifune’s character fades into the background as the film’s perspective fragments across a citywide police manhunt for the criminal, who turns out to be acting out of resentment against the economic system which the businessman benefits from. Lee’s camera, on the other hand, remains firmly anchored on his wealthy protagonist. Outsmarting the police and taking justice into his own hands, he manages to track down and apprehend the kidnapper (played with immense charisma and conviction by rapper A$AP Rocky), who is motivated by a personal grudge. While Kurosawa’s film visually maps the shattered topography of city life led high and low, Lee’s camera, as its title suggests, is less concerned with offering a systematic view than tracing an action-packed journey between these two poles.

There is a strain of conservatism here. Certainly, Lee realigns the story with the perspective of wealth, from the collective to the individual: a parallel could be drawn between Lee’s ownership of the company which produces his films, and his protagonist being the owner of a music production company. There is also a contrast with his ostensibly grittier 80s and 90s fare such as his 1989 masterpiece Do The Right Thing, which combined its provocative exploration of racial politics with a cast of working-class characters from a deprived Brooklyn neighbourhood. Lee’s personal politics aside, however, Highest 2 Lowest very clearly links this acquisition of wealth to the enabling of artistic freedom, as he tries to imagine a picture of wealth acquisition set apart from a homogenising, and accelerating, technological capitalism which stifles creativity, where individual excellence prevails over systematic market forces.

Highest 2 Lowest embodies, in its form, a desperate plea for artistic freedom in the face of this technological encroachment. Denzel Washington’s music mogul plans to buy back shares of his production company, in order to wrest control back from a board which wants to introduce artificial intelligence into its production pipeline. AI and social media alike come under scrutiny in Lee’s modernisation of Kurosawa. His resistance to these technologies is self-consciously delivered from the perspective of an aged techno-laggard, but also with a sincere resistance to the aesthetics of homogenisation which these technologies represent: Lee’s film is full of strikingly idiosyncratic directorial and editorial choices. In a move typical of the film, Lee re-tunes a taut, spare, and thrilling sequence in Kurosawa’s film, where the business mogul drops the ransom to the kidnapper from a train, into a frenzied Samba-scored montage, punctuated by changes in film stock, aspect ratio, and energetic cross-cutting between Washington’s character, a police chase and a festival crowd.

“Lee’s film, improvising over Kurosawa’s standard, formally embodies a freedom which might somehow survive these constraints”

These concerns are made reflexive by the fact that this originality emerges from what is essentially a cinematic repeat. In an interview, Lee insists that his film is not a remake, but rather a ‘reinterpretation’ of Kurosawa’s, in the ‘sensibility of a jazz musician’s reinterpretation of a standard song’. In this way, the film’s ethos of artistic freedom is also linked to its racial politics, considering jazz’s fundamental roots in America’s black community. Jazz’s heritage itself suggests the power of freedom to erupt from the bounds of oppression. Nowhere is this more lucidly expressed, in my view, than in the short film The Cry of Jazz (1959), itself a trailblazing work of black independent American cinema. In it, director Edward Bland argues that the musical form of jazz – improvisation over a fixed set of chord changes over a standard song – reflects the American black community’s reclamation of freedom from a society which has deprived them of a history and a future, an ‘eternal recreation of the present’, thus wresting creative agency from a system which seeks to ‘obliterate’ them. Artificial Intelligence may be doomed to eternal repetition of its training data, and contemporary pop culture may obliterate past and present with the perpetual repetition of market-tested remakes. As a last-ditch act of shoring up against these trends, Lee’s film, improvising over Kurosawa’s standard, formally embodies a freedom which might somehow survive these constraints.

Even Bland’s film, however, argues that improvisation was a dead-end, and that a new form of music must emerge from jazz (as if on cue, Ornette Coleman’s radical break from chord changes, The Shape of Jazz to Come, appeared later the same year, in November 1959). Lee’s jazz-inspired form also hits its emancipatory dead end in the sense that this freedom is increasingly only accessible via wealth. The film’s broad alignment of its wealthy protagonists with jazz and soul (Denzel Washington’s music producer doesn’t really keep up with contemporary music), against the rap represented by villain A$AP Rocky, might perhaps suggest another layer in its conservative politics. After all, prominently displayed in the penthouse of Denzel Washington’s character is a Basquiat painting of a Charlie Parker vinyl record, and a mural featuring pre-Bebop legends Lester Young and Fats Waller. These in-film examples of art turned into asset, lurking in the background, highlights the uncomfortable consequences of the intersection between art and wealth which Highest 2 Lowest is unable to fully untangle.

This political ambiguity, however, only strengthens Lee’s film. Where artificial intelligence is supposed to have all the answers, Lee’s film seems to do nothing but pose questions. The initial moral dilemma which, in Kurosawa’s film is resolved via a moral realisation, never gets resolved in Lee’s. The formal gaps in the film, its dissatisfactions that are also its exciting idiosyncrasies, are unavoidably linked to the contradictions in its politics. The way that Highest 2 Lowest occupies the space of these gaps makes it surely one of the most interesting films of the year.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026