‘Filth is my politics, filth is my life’: Rebuilding queer identity through Pink Flamingoes

In this personal mediation on sexuality and heteronormativity, Staff Writer Jude Jones situates ‘filth’ and non-conformity at the centre of queer cinema, and seeks to liberate ‘filth’ from shame

Content Note: This article contains discussion of self-harm and homophobia

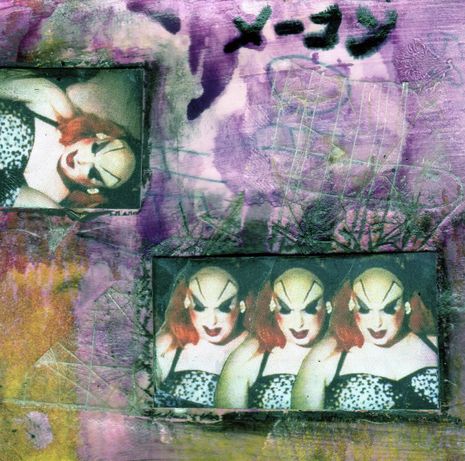

‘Filth is my politics, filth is my life.’ With that simple declaration, Divine — the monstrous drag queen in whom American director John Waters found his muse — pledges her allegiance to a peculiar thing: filth. It’s the leitmotif of his cult classic Pink Flamingos, a self-baptised ‘exercise in bad taste’ that unfolds as an orgy of depravity in which every taboo, from castration to rape to bestiality to murder, is transgressed for the camera in lucid detail as Divine vies for the title of ‘filthiest person alive’. The film itself is borderline unwatchable. Truth be told, I’ve only done so once and promptly vowed never to again. But it is also a film in which I find an esoteric beauty, a beauty so disgustingly and uniquely and undeniably queer. It is a film that preaches as doctrine a feeling with which I have long toiled — a feeling of filth — and chronicles with camp and crash violence its queer reclamation.

“It is a film that chronicles with camp and crash violence its queer reclamation”

I will always associate my queerness with my childhood bedroom at my grandmother’s house. Even now, I can build that room in my head, four walls in irradiant eggshell and a little guitar that sat ever hopeful in the corner. At night, I would stay up just to watch the world through my bedside window, staring into the dark still of a Lancashire countryside whose monolithic twilight was blemished only by the hypnotic red lights of the radio tower on Winter Hill. They clustered in the sky like an abstract constellation, one whose meaning I could never quite understand. I looked at them with curiosity; they contemplated me back.

Staring into their glow on such nights where time seemed to turn stagnant, thoughts would unfurl in my head in frenzied chain reaction, thoughts that always led me back to myself. Thoughts that led me to my flesh, to the red constellations that would appear there too as I itched at my skin in petty self-flagellation, hoping to scour off the dirt that I could almost feel manifesting as I careened towards an inevitable conclusion: something was wrong with me. And so I would sit cross-legged and alone in my bed, praying to a God in whom I didn’t quite believe and scratching, hoping that these rituals would make me clean. In that room I began to feel filth, and in that room I began to process what that meant.

“Embrace alterity, says Waters”

My feelings are unsurprising in retrospect. I grew up in a rural northern village where life seems forever paralysed in a 1970s Middle England Only Fools and Horses-induced fever dream and where every pothole-ridden road leads back to the same sandstone church, named for Saint Bartholomew. Here, queerness was never mentioned. And when it was, it would only be as the butt of some grotesquely laddish joke from some grotesquely laddish peer. ‘I would kill myself if I was gay,’ a friend once told me on an otherwise forgotten summer night. I think I humoured him with a laugh. To be gay was to be wrong, shamefully and irrevocably different.

But this is what Pink Flamingos celebrates, a film about nonconformity in which a behemoth of a drag queen in suburban Maryland, where everybody decorates their lawns with the same plastic pink flamingo figurettes, triumphantly vanquishes a miscreant straight couple by virtue of her superior filth and claims the title for which she so yearns. Through her queer filth, she becomes transcendent: ‘Divine is not only the filthiest person alive,’ Waters reminds the audience as we watch her eat a pile of dog faeces in close-up, ‘but also the world’s filthiest actress.’ Her depravity becomes so extreme that it outstrips the filmic world and enters the real one; it transforms, transcends.

“Divine’s depravity becomes so extreme that it outstrips the filmic world and enters the real one”

Filth then, for Waters, has a transformative potential for the queer subject. In a society constructed on heteronormative values to which queer people can fundamentally never conform, what’s the value in trying? Embrace alterity, says Waters. Queerness is filth in the sense of something that will likely always be disgusting to somebody, as something that will always be ‘other’ to a society whose survival is tied to the heterosexual family and its ability to biologically reproduce. If we learn to find our own beauty and power in our own community united in our otherness — with this ‘our’ importantly implicating the entire spectrum of othernesses that is ‘queer’ — then the shame around this ‘filth’ dissolves.

I can comfortably say that I’m gay at 20 and feel no revulsion at the word, even if only fairly recently so. Shame, however, is a flavour disgustingly fresh in my mouth, its aftertaste still tainting my family interactions and affecting who I become when I leave Cambridge to go back to the little village I call home. Here, I can sometimes still see the red of the radio tower lights glowing, pulsating almost, in the night sky. I sometimes wonder if they can still see me still too.

Filth was my life when I used to watch those lights in my youth and remains my life now, if only in a different way. And I suppose it’s in my politics too. Filth not as that same feeling of shame, but filth as a celebration of queerness as otherness, filth as a part of my identity, filth as freedom.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026

News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026