The weak and the strong: surviving the ‘male world’ of Westeros

Amidst the social media furore around its final season, Rianna Davis looks back on the last 8 seasons of Game of Thrones and discovers a worrying trend.

Major SPOILERS within

On Sunday 21 April, I set out on an impossible task: watching all eight seasons of Game of Thrones before episode 3 dropped. I was quickly hooked. Maintaining a Twitter thread while I watched, I experienced the rise and fall (and rise) of the Starks, the reign of the Lannisters, and the heroic Night's Watch, all in the space of six days. I was convinced that I had never watched such a well-written show which ticked all my period-drama-loving boxes. Up until season 6, that is.

Something began to frustrate me, and so I reviewed my lengthy thread. I had believed it was well-written because I felt so strongly about the female characters, which wasn’t something afforded by most shows. However, I neglected to see that, for the most part, these feelings were negative; I hated them, not because they were mean-spirited people who did malicious things, but because the characters themselves were weak and poorly-written.

None of these women are central in their own narratives, not in death nor in life.

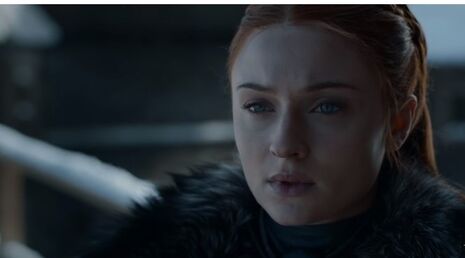

I had tweeted numerous times about how much I hated Danaerys for relatively superficial reasons: everyone falls in love with her, she makes mistakes, she doesn’t figure out how to use her dragons until the end of the show. The same went for Cersei and Sansa; according to my tweets, my dislike for the former was founded in her slight gap tooth, and the latter because she was a victim. And yet, my thread did not lack Arya adoration, nor did my disparaging comments about the male characters I disliked evoke such personal reactions.

Overall, my judgement of male characters was founded on much more justified grounds, and even the men who were categorically the worst - Joffrey, Littlefinger, Ramsey - had at the very least some satisfying closure. Very few women had a redemption arc or satisfying closure because they did not even have their own story arc to begin with. Their narratives existed within the wider storylines of male characters, and this was particularly evident in the cases of Shae, Ygritte, and Melisandre. All three of them had lived - and died - in ways which made us focus not on their deaths or even their achievements during their lives, but the men to which they had been connected.

Shae’s death particularly angered me: when we watch her die, the shot is of Tyrion, struggling with his emotions as he carries out what he believes to be just. The same happens with both Ygritte and Melisandre. In the former’s dying moment, she clings to Jon, and we see his feelings play out on his face as she laments that they should have ‘stayed in the cave’. With the latter, we watch her walk out into the snow as Ser Davos looks on, confused as she crumbles into bone and flesh. None of these women are central in their own narratives, not in death nor in life.

The inability of men to write convincing and multi-faceted female characters continues to frustrate.

But that still didn’t explain why I loved characters such as Arya, Sansa (post her Season 5 glo-up), and Brienne so much. They were women too, and had been very central in their storylines. The answer lay in the first episode. We meet Arya in a way which immediately indicates we must root for her, and Sansa in a way which indicates we must not. Sansa, primped and pretty, is praised for her embroidery skills while Arya, comparatively more boyish, looks on scornfully. She then hears the chuckles of the men outside, and sneaks away, shooting an arrow straight into the bullseye. When her older brothers turn to her incredulous, she mockingly curtsies. From the outset, the message is clear: Arya will prosper precisely because she so adamantly rejects those feminine constructs within her world.

She, along with Brienne, are anti-female characters, girls coded to be boys (read: can wield a sword better than most), and we only begin to fully warm to Sansa once she too rejects her flouncing femininity and embraces a tougher side, brought out from the trauma she experiences during the victimhood for which we pity or despise her. The women who are given the most screen-time, and their own admirable character arcs (which in Sansa’s case literally simply means ‘stops being a victim’) are the ones who are most closely identifiable with the ‘male world’ of Westeros.

While this whole narrative might very much sound like ‘the feminists strike back’ - isn’t this the future the feminists want? - the inability of men to write convincing and multi-faceted female characters continues to frustrate me. This is not a phenomenon confined to Game of Thrones, and now more than ever there is a pressing need to have more female writers (and writers of colour, because let’s not even get me started on the visuals of Missandei’s death) in the writing room. I want to see a range of complex women, not this tired dichotomy of weak vs. strong and the surrounding tropes that come with it. The reality is that until women are writing women, that probably won’t happen.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025

News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025