Review: Style over substance in Loving Vincent

While enthralled by its artistic beauty, Anna McGee was left unconvinced by the storytelling of this Van Gogh tribute

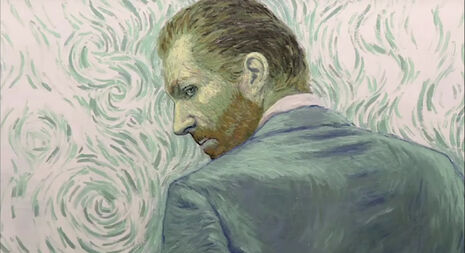

Many have often wondered who lives in that sleepy little village at the bottom of Vincent Van Gogh’s The Starry Night, and about the conversations of the evening drinkers in his brightly lit Café Terrace at Night. These scenes are so vibrant, so intriguing, so pulsating with life. Thanks to Loving Vincent, that curiosity is finally indulged: this feature film animates the art legend’s oil paintings, plunging us into the world seen through his eyes.

“The plot is flimsy and slightly monotonous, feeling more like a pretext to showcase beautiful artwork than a film in its own right”

Loving Vincent is an incredible technical feat: 124 artists were employed to paint 65,000 frames in the style of Van Gogh. Their precision cannot be faulted, with every brushstroke, hue, and composition in the style of the man himself. One painter revealed in an interview that she spent five months working on the project to produce just 30 seconds of the 94-minute film. In stop-motion style, each canvas was repainted several times with tiny variations – sometimes just a couple of brushstrokes – and photographed, before being edited together to produce a moving image.

So – as they are keen to let us know at the start of the film – this is an “entirely hand-painted” endeavour. That is not to say, however, that there are no actors in Loving Vincent: an all-star cast including Douglas Booth, Saoirse Ronan, Chris O’Dowd, and Aidan Turner first acted out the scenes in front of a green screen, and then were painted over by the team of artists. Although this might seem like a cop-out, the presence of famous faces is undoubtedly important in attracting people to this unprecedented genre of film. While the filming itself took less than a month, the painting took years: these actors played a comparatively small role in a much bigger enterprise.

The film’s story is set two years after Van Gogh’s death in 1890, and centres on the journey taken by the son of his Provençal postman and friend Joseph Roulin, who travels in and around Paris in an attempt to deliver the last letter the artist wrote to his brother, Theo. He soon discovers that the letter is undeliverable – as Theo in fact died just six months after Vincent – but finds himself becoming fascinated by the circumstances surrounding Van Gogh’s supposed suicide.

And so Loving Vincent becomes an historical whodunnit, as Roulin’s son begins to question whether Van Gogh really shot himself in a wheat field on that fateful summer afternoon. We meet a cast of characters from the village of Auvers-sur-Oise where the artist spent his final days – his doctor, landlady, boatman friend, and suspected lover – all of whom have different views on what really happened. In an homage to film noir, monochrome flashbacks give us glimpses into the last years of the artist’s life including, perhaps gratuitously, the occasion in which he severs his own ear and presents it as a gift to a prostitute.

As these are real-life events, there is inevitably no neat resolution to the mystery of Van Gogh’s death. Co-director Hugh Welchman has talked about the meticulous historical research carried out by his team in order to produce a factually convincing account – but the film’s allegation that the artist was actually shot by teenagers rather than committing suicide, an idea first put forward in a biography of 2011, has to it the ring of a conspiracy theory. As one of the characters points out with great self-awareness, such interest in the morbid circumstances of Van Gogh’s death somewhat overshadows the brilliant achievements of his life.

As such, the plot is flimsy and slightly monotonous, feeling more like a pretext to showcase beautiful artwork than a film in its own right. Style, rather than plot, drives Loving Vincent. In addition to the many invented scenes in a pastiche of his style, about fifty specific portraits and landscapes by Van Gogh are brought to life, albeit slightly adapted to fit the appearance of the actors. To jog our memory, there is a split-second pause when one of these paintings appears; given the iconic nature of so much of his work, the audience can get a kick out of recognising their favourite Van Gogh in motion. During the end credits there is a flipbook with all the paintings that featured, so we can check how many we spotted: perhaps this is more an art-lover’s game of bingo than a fully-fledged film.

Loving Vincent is cleverer than it looks, and the artistic process is more impressive than the final product itself. While audiences are certain to be wowed by this painstaking, witty experiment in film and art, one cannot help but be left wondering if this is just a gimmick rather than the pioneer of a new genre

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026