Zoetrope: the quiet politics of Hayao Miyazaki

In this week’s column, Ian Wang approaches the messages hidden in the films of one of Japan’s greatest animators, and how they compare to his more overt ideology

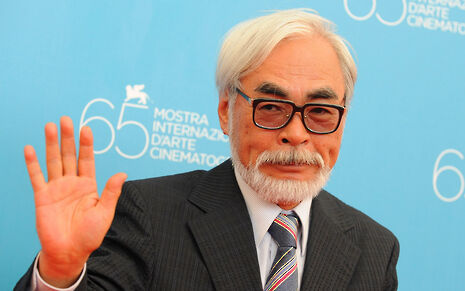

Hayao Miyazaki is one of Japan’s most revered filmmakers. He is also one of the Japanese government’s harshest critics. When PM Shinzō Abe revised Japan’s constitution to allow for increased militarisation in 2014, Miyazaki, a staunch pacifist, was not shy about his disgust. In fact, Miyazaki is not shy about most things. Despite his friendly demeanour, he is a famous curmudgeon – a clip that went viral last year shows him being pitched an AI program and responding to it by saying “I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself”. Miyazaki’s belief in the inherent dignity of human life is unwavering, and it has led to everything from an Oscars boycott in 2003 in protest of the Iraq War, to being labelled a “traitor” by Japanese conservatives for his belief that the Japanese government should offer a “proper apology” to Korean ‘comfort women’.

“Humanity’s self-centred myopia is what ultimately becomes the villain of the film”

At first glance, it might seem hard to square these fierce political beliefs with Miyazaki’s gentle, reserved filmmaking style. But though the politics of his films may be soft-spoken, they manage to resonate in ways that a simple statement to a newspaper cannot. In using the fantastical, kaleidoscopic landscapes of his films as the vessel for his political ideals, Miyazaki constructs a vision of the world in which these can genuinely be realised and explored; a world in which war and environmental degradation do not have to be treated as necessary evils; a world in which, actually, humans are not necessarily the good guys, and they are held directly and immediately accountable for their actions.

Although Miyazaki’s colleague, Isao Takahata, probably takes the cake for the best-known animated war film – 1988’s harrowing Grave of the Fireflies – the spectre of war nonetheless looms large over much of Miyazaki’s filmography. Both directors grew up haunted by the long shadow of WWII, which Miyazaki described as “a truly stupid war”. When it came to depicting its aftermath in his films, then, Miyazaki did not hold back – in his sophomore feature, Nausicaä of the Valley of Wind, the protagonist’s world has been overtaken by a sprawling Sea of Decay, where nothing grows and the air is poisonous, a post-apocalyptic landscape directly attributed to human violence.

However, this reality – that human violence caused the crisis they are living in now – is ignored by the aggressive kingdom of Tolmekia, who simply blame the decay on Mother Nature and set out to destroy the Sea completely, including all its wildlife. Miyazaki’s evisceration of humanity’s inclination towards violence is perhaps clearest in his depiction of cruelty to animals. In one scene, a band of panicked soldiers scramble to shoot a giant insect, afraid that it might retaliate and attack them. Where they can only see malevolence, however, the film’s titular protagonist, Nausicaä, has the sensitivity to recognise that, if humans were to leave the insects alone, they would do the same in return. As such, she simply encourages it to fly away, and it does. Humanity’s self-centred myopia – of only being able to see the backlash of the natural world, and not the human violence that triggered it – is what ultimately becomes the villain of the film.

“He still has a belief in the good of humanity, and that humanity can, one day, do better”

It might be tempting to dismiss Miyazaki as a simple misanthropist without a consideration for the nuanced realities of conflict and human life, but he is also capable of enormous moral complexity. One of my favourite Miyazaki characters is Lady Eboshi, the militaristic matriarch of his epic historical fantasy Princess Mononoke. Eboshi’s mission is to clear the forest and build a prosperous town for her people, apathetic to the damage it causes to the forest’s animal inhabitants and going as far as to decapitate the almighty Forest Spirit in order to further her goals.

Eboshi is ultimately the antagonist of the film – slaying the Forest Spirit causes a wave of death that nearly kills everyone and everything in the valley, including the townsfolk – but she is also a protector and a progressive. Her community of Irontown is a refuge, offering safe haven and work to disabled lepers and former brothel workers who might otherwise be shunned by society. Though Eboshi later becomes a symbol of the same prideful ignorance castigated in Nausicaä, her intentions are good, and she displays a radical amount of kindness and inclusivity for a medieval leader. Mononoke’s central conceit is not that humans are inherently evil, but that human ignorance, and their failure to communicate and empathise, is ultimately humanity’s own downfall as much as it is that of the surrounding natural world.

Eboshi also exists in a long tradition in Miyazaki’s films of complicated, independent, and often heroic female characters. Almost all of them feature a female protagonist, and each one faces the obstacles presented before her on her own terms; though many of these protagonists do fall in love with men, it is more often than not the case that they get themselves in distress, and it is the damsels who have to save them. In Howl’s Moving Castle, Sophie, a young girl cursed into old age by a disgruntled witch, is initially helped by mysterious wizard Howl, only to discover that Howl is a self-destructive wreck who needs her more than she needs him. Sophie – whose old age ends up being less of a curse and more of a liberation, a sharp contrast to patriarchal ideals of youthful femininity – rescues Howl by returning his heart to him, a conclusive gesture that effectively saves the day.

Miyazaki’s work offers us an alternative vision of humanity, a vision in which we are ultimately able to see our own short-sightedness, our own lack of empathy; in which we can see the consequences of these faults, and we can find ways to correct them. Although Miyazaki’s political commentary paints him as a cynic, I think his films suggest that, in spite of it all, he still has a belief in the good of humanity, and that humanity can, one day, do better

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026