Found in Translation: upheaval through the cinematic lens

Contrasting Black Girl by Ousmane Sembène and White Material by Claire Denis, Madeleine Pulman-Jones looks into the themes and visual representation of immigration in foreign film

This August, The Guardian published two pieces on the refugee crisis: one on the return of more than one thousand refugees to the woods around Calais, and one on the persistence of British colonialism in regard to the refugee crisis.

That same August, as I walked out of a cinema, a face captured my attention. The face was that of a young black woman at the centre of a film still at the bottom of a large white poster advertising screenings of films about migration. I stopped and leaned in to read the small print beneath the still – “Black Girl (1966) by Ousmane Sembène”.

The face was not looking at me, but gazing up, beyond the frame, towards something I could not see. It might have been the sun, but if it had been her eyes would have been squinting, and they were wide open. Watching the film later that evening, I came upon the moment from the poster. It had not been the sun, but it had been close enough for this “black girl” - it was the home of her new employers in France. What she did not yet know was that, like the sun, this too could burn.

“Though expressed in aesthetically opposite ways, the films share a common objective”

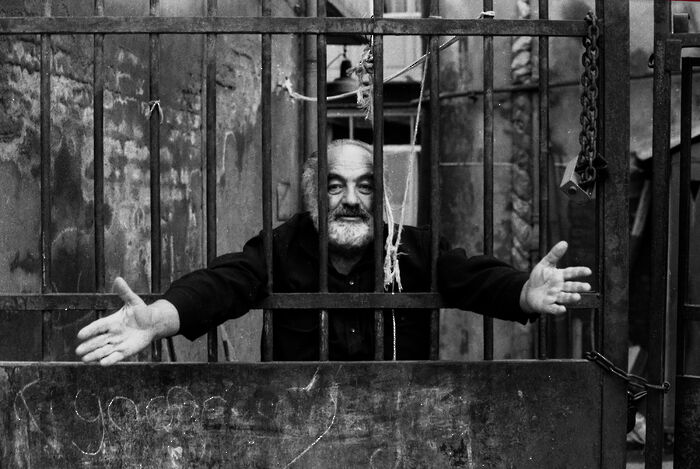

I was reminded of a similar moment in Claire Denis’s White Material (2009), set in an unnamed francophone African country in the midst of civil war. Riding a motorbike down a dirt path, Isabelle Huppert’s face pops in and out of frame in extreme close-up – eyes closed, beaming ecstatically at the sun. Instead of lingering on her face, Denis’s handheld camera pans delicately up Huppert’s outstretched arm - her palms opened wide, her fingers reaching hungrily into the air as though to snatch the sun from the sky. It matters that the most potent image in the visceral first act of White Material is neither a man locked in a burning room, nor armed soldiers holding up a bus, but a white woman’s face.

Sembène’s titular “black girl” is Duana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop), who moves from Senegal with a French colonial family to Antibes to work as a nanny. Despite her dreams of a better life, Duana finds herself isolated and treated like a slave by her employers. By contrast, Denis’s film centres on the last plantation owner, Maria Vial (Huppert), in an unspecified African country, who refuses to leave her land.

White Material, made 43 years later, is, in some ways, Black Girl turned inside out. Where Sembène had used the cinematic contrast between black and white to tell the story of a black girl in a crowd of white French people, Denis employs the same contrast in narrating the story of a white Frenchwoman among black Africans. Though expressed in aesthetically opposite ways, the films share a common objective – to demonstrate, through the visual representation of isolation, the cruelty and evil of one while giving justice to the other.

“Huppert, the most daring actress of her generation, is at the top of her game here”

Denis’s and Sembène’s cinema is one of extremes, most clearly manifested in their painterly use of colour as metaphor rather than being manifested in gratuitous violence. True, Denis’s colour cinematography cannot compete with Sembène’s high contrast black-and-white in terms of the striking contrast in both skin tones and atmospheres, but what Denis’s use of colour lacks in punch, she makes up for in nuance.

What Denis manages to capture more subtly than Sembène is the way that the struggle for possession of land is bound to cultural identity. In almost every shot, Maria Vial’s auburn hair and tanned skin merge with the dry soil she ploughs. Denis is by no means condoning Vial’s colonial appropriation, but rather immersing us in her lived experience. The cruel reality of Vial’s insensitivity would not be half as effective had we not empathised with her to such a degree. Huppert, the most daring actress of her generation, is at the top of her game here, demonstrating her talent for playing typically unsympathetic characters with a level of composure that elevates their struggles to the height of classical tragedy.

Black Girl is widely credited with establishing the Saharan African film industry, and remains intensely powerful, not least for focusing on such a complex woman of colour. A crucial double entendre is lost in the English translation “Black Girl” of the original La Noire De…, which literally translated means either “The Black Girl from…” implying her nationality, or “The Black Girl of…” implying that she belongs to someone.

This duality takes the metaphorical form of a traditional Senegalese mask. First given as a present to her French employers and later taken back in a bid to reclaim her own identity, the mask motif marks the pinnacle of Sembène’s articulate symbolism. Not only a reminder of Duana’s cultural dualism, but when worn by various characters, it is a subtle reminder of the duality of fiction and cinema itself.

Both of these films are complex and rewarding – such a brief study cannot do them justice. What is undeniable is that even taken purely at face value, these films highlight the ways in which cinema is both a medium for us to access minority voices as well as a vehicle for filmmakers themselves to give justice to the repressed, taking advantage of their position of authority

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026