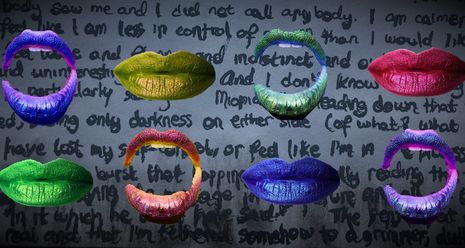

My stiff upper lip

Sionna Hurley-O’Kelly embarks on a new relationship with her most English of stiff upper lips, seeking to free her identity of the emotionality of old

Content Note: This article contains discussion of hospitalisation, excessive drinking and illness

I woke up to the familiar suspicion:

“I think I might be a terrible person.”

This statement may well be true, but my sense of self-worth on that Friday morning was founded more on the two bottles of wine I’d had the night before than on any Cartesian rationalism. Bibo ergo sum. Curling myself more tightly into the blankets, I contemplated the merits of being a disembodied subject of cognition: for one thing, I wouldn’t feel quite so nauseous. And the unwelcoming prospect of verticality would no longer be on the cards. But the shame I was feeling would remain.

At this point in my twenty-third year, I was well-versed in the process of hangover guilt. The sense of self-loathing was, I reminded myself, down to alcohol withdrawal. It was all about serotonin. After all, what heinous crimes had I actually committed? Feeding my burger bun to a dog on a bicycle. Shouting outside Pembroke in broken French. Salsa dancing… Rather questionable indiscretions but nothing to get me publicly ostracised. What was bothering me most wasn’t these more obvious embarrassments. Instead, it was a moment of emotional openness.

“At this point in my twenty-third year, I was well-versed in the process of hangover guilt”

I’d been sitting in one of the nightclub’s stickier booths. From out of the tumult of body odour and artificial smoke, a flatmate had danced over, bringing with him an Espresso Martini and a joie de vivre that I was about to devastate.

“Imsovryunshappy,” I declared.

Or, rendered less phonetically, “I’m so very unhappy.”

“Oh,” a look of nervous anticipation entering my flatmate’s eyes, “Shall I get you some vodka?”

The vodka was procured but no further explanation given for my outburst. Instead, I spent the next thirty minutes attempting to persuade the man from Room 7 that I was not, in fact, “so very unhappy”. That au contraire, I was positively fine. That my moment of emotional incontinence was completely out of character. And that I was never usually so horribly sombre.

Such a display of emotional reserve is ironic, following an adolescence spent in the guise of a Greek widow. Until the age of nineteen, I was famed for my regular displays of ululation in public settings, for writing sad poetry — often about nature, frequently in French — and for styling myself in the fashion of Catherine Earnshaw, with a partiality for moorlands to boot. Throughout my teenage years I’d retained the assumption, normally held by small children and distressed members of the gentry, that if only I cried loudly enough, somebody would come along to save me. It wasn’t until my first year at university that my attitude changed.

“The person I want to be once again thwarted by the person I am”

After spending Michaelmas term in a euphoria of personal freedom, academic pleasure, and a sense of belonging, the New Year had ended this idyllic situation. A number of factors combined to produce a general sense that I was tumbling away from the happiness of the previous months. As per convention, I made my feelings known whenever I could, still labouring under the false assumption that, if only others realised how sad I was, someone would surely come to rescue me. But nobody came. Instead, friends began to distance themselves from me and my emotional outbursts. “I don’t think she’s coping,” I overheard one flatmate say to another. And then, “She needs to get a grip.”

It was only when I landed myself in hospital with a particularly bad virus that I began to stop seeking the emotional support of others. I realised — as anybody who spends a fortnight periodically sweating, sneezing, and vomiting realises — that desperate pleas for help were not as alluring as I’d previously imagined. The realities of physical illness showed me that I didn’t want to be a victim. That I wanted to get better. And that the way to do so was not by lying back and wallowing until somebody came to save me, but instead by saving myself.

Nowadays, emotional openness gives me an unpleasant aftertaste. When I reveal my feelings to someone else in anything other than a middle-class, stiff-lipped, third-person-passive, second-cousin-once-removed, impersonalised manner, I’m left with not only my original troubles, but also a sense of something like failure. It’s not a question of guilt. I mollify my fears of burdening society through vegetarianism and bamboo toothbrushes. It’s a matter of shame. Having tried to build myself into someone who can save herself, I want others to see me this way. When I express my feelings, my carefully constructed self-narrative — my identity — falls apart. The person I want to be once again thwarted by the person I am.

But it’s not just a matter of weakness. There’s something concrete about silence, something stable. Emotions, on the other hand, are chaos. They rush in and out of view, constantly morphing, slipping away as soon as they arrive. Emotions are erratic. And emotional vulnerability is incompatible with maintaining a stable identity. As a teenager, my feelings were my identity. Now, I’d like to see myself as a bundle of qualities and principles and integrity — and while I keep my emotions hidden, I can. But once I share my feelings, once I let them affect what I say and do on the outside, I have to admit that they’re part of who I am. I have to admit that I’m made up not of virtues and mantras and timely witticisms, but instead of emotions and reactions and (somewhat faulty) defence mechanisms. It’s a matter of identity.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026