Rejection, power and excellent cheekbones

‘Love certainly is a cruel mistress’, Sionna Hurley-O’Kelly observes in this tale of tripos crushes, romantic rejection and ridiculously high pedestals

The rejection came as a blow. He had excellent cheekbones and a strong knack for discussing native birdlife – something rare in a man of this generation. And more than any of that, I’d really thought we’d suited one another. Star-crossed, as they say. A match made in heaven. But Love’s a cruel mistress, and what had been a very enjoyable first date was now in the midst of heading down the well-trodden path: “Let’s just be friends.”

“I’m sorry,” he concluded, furrowing his brow in an obligatory sign of repentance. His left foot was turned pointedly away from me and down the darkening city street towards home.

I responded with an equally obligatory shrug of unconcern, “Not at all. It’s fine.” In this tango of social etiquette, we were both playing our parts impeccably. And then, for good measure, and as though in order to rebalance some invisible scale, I added, “I’ve actually been on your end of things a lot recently.”

By this point in my romantic odyssey, I’d become quite adept at the art of being rejected. My preferred response was indifference (“Oh well, I wasn’t all that keen in the first place – native birdlife is such a bore.”) While another favourite was the above tactic of citing countless jilted suitors, wallowing inconsolably in various darkened rooms and melancholy graveyards.

“I found myself auditioning for the Antigone in a bid to allure the director with my thespian prowess”

But these coping mechanisms had developed slowly and painfully, the product of many days spent chasing young men around lecture halls and libraries, attempting desperately to re-establish some semblance of dignity with ever-more elaborate shows of “being just fine” without them. On one occasion, an unfortunate friend received two packets of custard creams to apologise for a recent attempt at courtship. On another, I found myself auditioning for the Antigone in a bid to allure the director with my thespian prowess. I didn’t get the part.

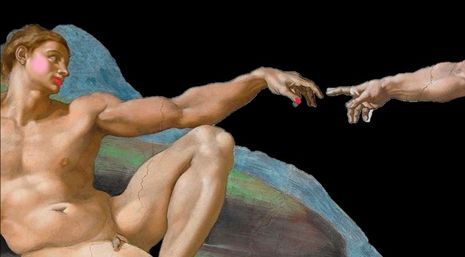

While the humour of such pageantry isn’t lost on me, this comedy coexists with a more painful side of rejection. By admitting our feelings for a person, we place them on a pedestal from which they may judge, accept, or reject us. The prestige we’ve given them makes their evaluation all the more forceful, their rejection even more damning. We’ve become the kingmakers to our own destruction. And so we try to rebalance the scale: a desire to reclaim the power we’ve surrendered yields increasingly manic attempts to restore our reputation. We follow young men into libraries and lecture halls, we hold conversations at inordinate volumes in the hopes that they might hear just how interesting we are, and we make every attempt to show them what an excellent time we’re having on our own. And in doing so, ironically, we manage only to tether our self-estimation more tightly to their judgement.

“At the moment of rejection, a metamorphosis seems to occur”

Being in love is romantic for only so long as it’s reciprocated: once our feelings are revealed as one-sided, they lose their attraction. They become pitiable at best, pathetic at worst. From Shakespeare’s cross-gartered Malvolio, to the luckless Gunther of Friends, the jilted lover exists in our cultural vocabulary as a synonym for pantomime villainy. Weaklings and sycophants. Incidental fodder for jokes. At the moment of rejection, a metamorphosis seems to occur. The blushing cheeks of a passionate hero become the tear-stained blotches of a red-faced fantasist. Desire becomes obsession. Hope becomes delusion.

By the final year of my undergraduate, when I met with the young ornithologist and his excellent cheekbones, my approach to rejection had altered significantly. I’d come to process the experience more stoically: to resign myself to defeat and to ignore the goadings of pride and temptations of hope that pushed me to chase after the people who’d rejected me and change their opinion. And what’s more, I’d learnt to avoid rejection where I could. Learnt to keep my feelings hidden. To dismiss the Hugh Grants and Paul McCartneys of the world with their encouragement to “go out and get her”. That mantra had lost its nobility somehow, mingled with the malodour of romantic refusal, and the price of rejection was no longer one I was willing to pay for empty hope. Instead, I’d learnt to love silently, keeping my emotions unspoken and enjoying feelings of affection which were unspoilt by rejection.

My heart-shaped life

The world is full of power dynamics – topsy-turvy storms of emotions colliding, fluctuating patterns of attraction, strange cattle-markets of romance where our own affections decide who gets to put a price on us. By loving, liking, lusting after a person, we raise them up on some invisible scale of social relations. And when we admit our feelings, this scale is revealed and both parties are forced to watch uncomfortably as one side sinks. So we thrash about in ever-more frenzied bids to alter their opinion, to reassert ourselves, and prove that there’s been some dreadful miscarriage of justice. Eventually, perhaps, we learn ways to cope with these power dynamics: to feel more quietly, to love less readily, to say, “Not at all. It’s fine.” And, ultimately, when we can no longer take the burning shame of refusal, we stop risking rejection entirely. We keep our feelings unspoken, watching our muses from the side-lines, fluttering every time they look at us or speak to us or laugh with us, before retreating quietly back to our seat in the far-off spectators’ stands. We never tell them.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026