World Book Day and the world of books

With World Book Day just passing, Lara Poole shares a retrospective outlook on this celebrated day to demonstrate how her relationship with reading has changed over time

For the past few years, I seem to be reminded of World Book Day halfway through the day itself. I smile as memories flood in of dressing up for school and getting those little £1 book tokens that felt comparable to Wonka’s golden ticket. At nineteen, World Book Day is no longer a count-down-the-sleeps event but instead an opportunity to indulge myself in memories of when I was the target demographic.

“Reading wasn’t a task we had to get through before we returned to life – it was life”

The clearest World Book Day in my mind was when I was in Primary One. I went to school with a massive cardboard hat my aunt made me, complete with a rainbow, a pot of gold and cutouts of the Rainbow Fairies stuck to pipe cleaners flying around my head. Now, I’m not going to lie to you – I was feeling pretty competitive. There was a prize for the best one and I wanted to win. What I wasn’t competitive about though, was the book itself. At six, reading was not something you did to help expand your mind or cultivate an image of yourself as intellectual, well-rounded, relatable but quirky. The fact that every other girl in the class also read the Rainbow Fairies brought a sense of community, not competition. These were the days when reading never felt like an obligation or an attempt to prove myself. I’d try to convince Mum to read as much of The Magic Faraway Tree as we could possibly get through in one sitting, or stay up with my little sister listening to Dad read us Nanny McPhee. Reading wasn’t a task we had to get through before we returned to life – it was life.

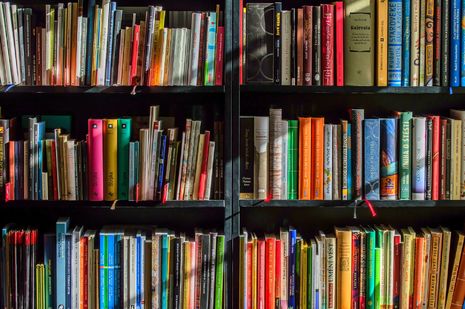

As I moved through school, however, this quickly changed. While reading was always something that brought me great joy, I began the shift from seeing reading as a fun pastime to a part of my identity. Now I laugh at myself when I think back to when I was ten years old, being too embarrassed to ask for the Diary of a Wimpy Kid books even though I thought they seemed really funny. Instead, there I was bringing this absolute brick of the entire works of Sherlock Holmes to school under my arm, carefully studying each word and pretending I understood what was happening in A Study in Scarlet.

“We allowed ourselves to be spellbound by the simple power of storytelling”

Reading in your foundational years touches you in a way that feels almost sacred. Now studying English at university, I love chatting with my coursemates about the literature we love and hate. Still, nothing quite touches on the innocent enthusiasm that can only be evoked on the English group chat when we bond over a shared favourite children’s author. My favourite message has been my friend’s: “This is so exciting! A group of people who appreciate Flat Stanley!”. There’s just something about realising your new friends also grew up wanting to join the Secret Seven, wanting to find Narnia and being slightly disturbed at anything by Jacqueline Wilson. As children we went into these books without an agenda: we weren’t looking to be intellectually challenged or changed emotionally. As a result, we allowed ourselves to be spellbound by the simple power of storytelling.

In saying this, the realisation that lots of my favourite childhood books, such as The Secret Garden, contained harmful stereotypes and blatant bigotry has made me realise that this comforting space I had a child was often an exclusionary one. This is not just a problem of the past either; with David Walliams’ novel The World’s Worst Children, published in 2016, being criticised by podcaster Georgie Ma last year for “normalising casual racism from an early age”. From racist stereotypes to strict gender roles to the fatphobia that plagues much of children’s literature, I must recognise that despite my tendency to romanticise my past reading experiences, I should be careful to not necessarily idealise the books themselves.

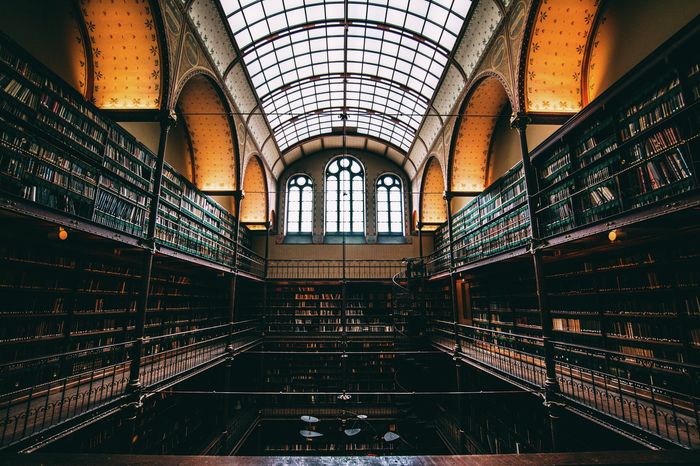

In romanticising my past reading experiences, I can also forget that the biggest obstacle from me enjoying reading to the fullest again is myself. Thinking back on World Book Day, and my younger self who would rush all her schoolwork so she could read under the desk, I begin to wonder if back then I had read right. So, as I sit and wait on my book to arrive for my college’s book club and think about the Easter holidays, I am filled with hope. Perhaps this will be the break I get through my TBR list, looking to my shelves of unread books not with stress, but excitement.

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / News in Brief: Maypole mentions, makeovers, and moving exhibits4 January 2026

News / News in Brief: Maypole mentions, makeovers, and moving exhibits4 January 2026