Me, nana, and my terrible Bangla

Contemplating her relationship with her late grandfather, Senior Features Editor Nabiha Ahmed explores how second-generation immigrants can navigate language barriers within their families

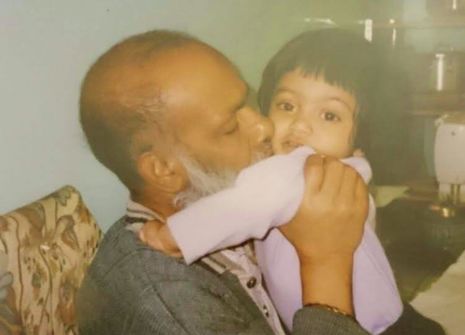

Not many people thrive in the sound of silence. In my nana’s lifetime, however, he mastered silence as a love language. I’d stay with my grandfather as a toddler whilst my mum was at work and he’d mix equal parts of Ribena and water for me; I’d smugly watch CBeebies whilst silently drinking my cavity-inducing concoction from a baby bottle. In later years, nana became my silent chaperone on my pilgrimage to primary school. And upon arriving, he’d silently watch me from the gates before the sound of the bell marked the end of his covert surveillance. Once old enough to walk back from school alone, I’d often be welcomed with nana’s sugary cakes — my mouth too stuffed to engage in any conversation.

But when that baby bottle wouldn’t work, he’d substitute it with sweet words and tell his “fences” — my Bengali grandad’s attempt at the English word “princess” — that mum was coming back soon. When morning busses were slow, he’d angrily shout nonsensical phrases that morphed English and Bengali, complaining that the driver was going to make his beloved “fences” late. Approaching school, he once said that “shokhol fuwayn shaytayn” — loosely translated from Bengali as ‘all men are the devil’. Nana (seemingly the pioneer of the “men are trash” movement) probably should’ve cared about my rotting teeth more than the possibility of eleven-year-old me befriending boys. But what mattered was simply that he cared.

“A hungry silence only satiated by the mosque’s call to prayer”

During his funeral, there were soundless tears, wordless hugs, and quiet prayers. A hungry silence only satiated by the mosque’s call to prayer, signalling the impending funeral prayers. A stubborn silence that only agreed to be fed by hands raised to remember him through God’s words. And whilst all of this somehow felt very specific to the man who loved silence, it also reminded me of a painful truth. There was a scarcity of meaningful words exchanged between us in his native language before he died. I began to wonder if not being able to bond over that shared taste of Bengali with nana meant that I didn’t get to know him well enough in his lifetime. I’d never asked him about his journey to London from Bangladesh, nor about his life before grandchildren. Was the language barrier also a barrier to knowing who he truly was?

Whilst I could understand almost everything nana said in his mother tongue, the Bengali language has never felt at home on mine. Being asked ‘Are you good?’ in Bangla by him could trigger thoughts of a thousand replies, but my beginner Bengali skills would reduce them to a short reply of “ji-oy”, meaning “yes”. Whenever Nana spoke in Bengali, I’d coyly reply with “ji-na”-s and “ji-oy”-s — safe phrases that didn’t make me feel like the unwanted guest at Bangla’s dinner table. And because of this, the taste of Bengali always felt like one I could precisely describe but one which I’ve never truly tasted myself. And there is a sense of self-imposed embarrassment that I have never truly made room in my mouth for the language of my motherland.

“Those arms of the English language have gripped me too tightly”

The Bengali language for me, though once half-alive, died with him in many ways. When I occasionally tried the language for size on my tongue when speaking to my nanu (my grandmother), there seemed to be no muscle memory of it. Part of me wanted to blame my family members for discouraging me, who’d greet my failed attempts to speak Bangla with teasing. But I also felt shame. Shame because my elderly grandparents left the cradling arms of Bengali to develop a relationship with their English-speaking granddaughter. Shame because Little-Nabiha would snicker in the bosom of English as a first language when she’d hear nana say ‘fences’ or shout nonsense at bus drivers — not unlike how people tease me when I speak Bengali. Those arms of the English language have gripped me too tightly, making it harder to reach out to the people in my family who have never felt their embrace. And I am only beginning to unclasp the hold that the fingers of English have held on my tongue for so long.

Not unlike the way nana balanced utilising and temporarily discarding the comfort of silence, I balance between embracing and challenging comfort when it comes to language. When nanu calls, I force myself to speak Bengali; even those awkward silences that indicate my inability to find the right Bangla words are appreciated by her. I beg my father to speak in Bengali when I can see him trying to verbalise his anger through English, a language that will never fully understand the extent of his emotion. In doing so, I see his facial expressions transition from that confused space between speech and thought into ones resembling relief, pairing them with Bengali gestures and intonations that I will never replicate but have come to understand. I jokingly greet my mum with “what you saying?” simply because I want to, and because she has learnt what they indicate even if she doesn’t know what they precisely mean. By no means have I found a definitive solution to language barriers for Bengali-British families. But what I have found solace, in balancing between retreating into the warm embrace of my native language and knowing when it would be good to try the embrace of another.

Twenty Pakistani mangoes lay on the kitchen table, bought by my mum after I’d nonchalantly mentioned I liked them once. The offering of leftover Papa John’s “fixer” by my nanu leaves me smiling. That feeling of my brother silently pulling me into a long hug — after God knows how many years — straight after burying my grandfather is a feeling I still cling to four years on. The words “shokhol fuwayn shaytayn” ring in my ears as a grown woman. Through small pleasures, Nana’s love is kept alive. He was my first love and my first loss. And my love for him has made me realise that I cannot afford to lose Bangla.

In memory of Danis Ullah

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026

News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026 Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026

Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026 News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026

News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026