Thoughts from an Alumnus

“You probably can conquer Cambridge alone, but then you’re unlikely to remember it fondly’ an anonymous past student reflects on their experiences at Cambridge and the relationships they had with their peers.

I spent four years at one of Cambridge's oldest colleges, not the grandest but perhaps the prettiest, and one of the most comfortable in its own skin. Four years more have passed since I left, four years in which a stint back home interrupted my adventures in two Italian cities, Ravenna and Florence, where I live now. It all makes four years seem like a long time to have spent in the same town, waking up in the same college - or at least commuting to it - every day; sitting in a similar seat in the same library opposite the same faces, before facing them again over dinner.

"I secretly admired my friends who could quite comfortably occupy the same library desk for seven or eight hours at a time, never stirring"

Not that I would ever scorn routine. I might have scorned it at the time, but only because I wished I’d had one. I secretly admired my friends who could quite comfortably occupy the same library desk for seven or eight hours at a time, never stirring. Did it really come so easily to all of them? I wondered with envy and a touch of disdain. Was it competitive industry that drove them? Some people, of course, will always carve out a trench and make of it their fortress, but not everyone. Some are excessive, some are efficient, some are scattergun. That's just the variety of human life. Be sceptical of anyone who tries to foist their methods upon you.

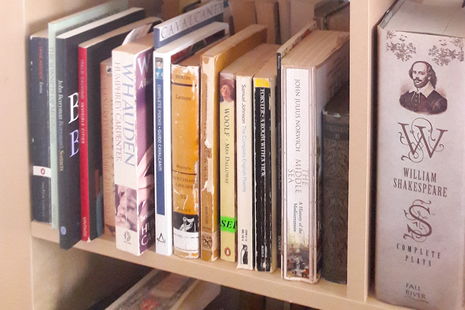

Thankfully, our supervisors trusted us. It was they who kept me excited about what I was doing, and fought to keep me on track when I threatened to stray. They pulled off the vital trick: they cared about the literature we were reading and talking about, and they made sure that we cared about it too. It might have been familiar ground for them, but they treated it as the virgin snow that it was for us.

Wonderful though my English supervisors were, though, they had some fierce rivals. I may have been in the first year to shoulder £9,000 p.a. in fees, but I was in the last to reap the benefits of Paper 7, which allowed English students to discover a bit about the literature of a foreign language. I went for Italian, having read Dante's Divina Commedia in the Penguin translation, and found myself sitting opposite the translator himself. He was of the old guard - older than his college, in fact - and one of the kindest, funniest and most brilliant people I have ever met. He supervised me for most of my Cambridge career, starting in Michaelmas second year, when my incipient portfolio of essays on various eighteenth-century poets had me at a low ebb. “Hmm, yes,” he sympathised: “I don't really ever think about the eighteenth century.” Two years later, I was enlightened, and told him that the eighteenth century was actually starting to fascinate me. "Dear me," he said, "what a confession." To the essays that he himself set us, his attitude was thoroughly modern: "They come when they come."

I hope that all supervisors appreciate the impact they have. If they are excited by what they're teaching, even after decades of teaching it, then chances are that their students will be excited too. Some of them, whatever their enthusiasm for their subject, plainly weren't enthused about communicating it. Jealously guarding one's research is perhaps a habit ingrained by years of professional rivalry. I would urge all academics to follow the shining example set by another of my Italian supervisors, who reposed such trust in his students, such faith in our insights, that he even went so far as to employ us. Thus I passed the summer holidays after graduation by translating an article of his into English.

It's funny how time changes your perceptions. In my fourth year, when I was doing my Masters, I was already taking stock of my Cambridge career, nearing its end. At that point, I was sure that first or third year had been my best. Not second: never my second year, though it finished in by far my strongest academic performance. Now I am pretty well convinced that second year was the most fun. There were far fewer awkward getting-to-know-yous; we had more freedom in what we read and wrote about. We had more confidence, we put ourselves forward for more things; I assumed leadership of the college's poetry society. And finals were still far enough away.

"I failed to adequately fill their shoes: my third year was a story of self-centredness."

Perhaps most importantly, though, we still had people to look up to. Many of my great sophomore memories were forged at parties dominated by finalists, who were about to head out into the big wide world. Unlike at school, age conferred no sense of rank or status; the third-years I knew were just really great people, who wore their academic battle-scars lightly. A year later, I failed to adequately fill their shoes: my third year was a story of self-centredness.

So if I can give any advice to current students, it would be this. Don't worry about how anyone else goes about their business, but do be aware of the ways in which you might affect others. Ask what your college can do for you, but also ask what you can do for your colleagues. Whether you know it or not, they are almost certainly lending you a helping hand. You probably can conquer Cambridge alone, but then you're unlikely to remember it fondly.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 Fashion / The art of the formal outfit 18 December 2025

Fashion / The art of the formal outfit 18 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025