Creative arts and the school curriculum don’t go together

Features Editor Ashna Ahmad explores how the confines of the school system made her arts education restrictive and uninspiring.

“The thing is, I don’t hate art, and I never have hated it. I love it. From a very young age, I have been singing and acting, visiting art museums and theatre productions, reading and writing voraciously, and above all, just being creative and expressing myself. And it’s sad, and symptomatic of the deep flaws in our education system, that this has been misunderstood.”

These are a few sentences from the introduction to my final portfolio for my Silver Arts Award, an extracurricular, multidisciplinary arts qualification which I was lucky enough to take in Year 10. I was certain that I wanted to take this qualification as soon as I heard about it — but I was equally certain that I never wanted to study a ‘creative’ subject at GCSE. My experience with the creative arts at school, from Reception to Year 9, was uniformly terrible.

Having a disability which affects my fine motor skills was pretty prohibitive when it came to enjoying art and design-related subjects in school. Ever since my very first art lessons, enjoying the visual arts was equated with being able to produce high-quality works of visual art — something I, with my clumsy fingers, could never do. More specifically, I would never be able to produce anything which would fit the rigid standards of curriculum-assessed work.

“Arts subjects had all the rigid quantification of maths or science lessons without any of the pretence of utility.”

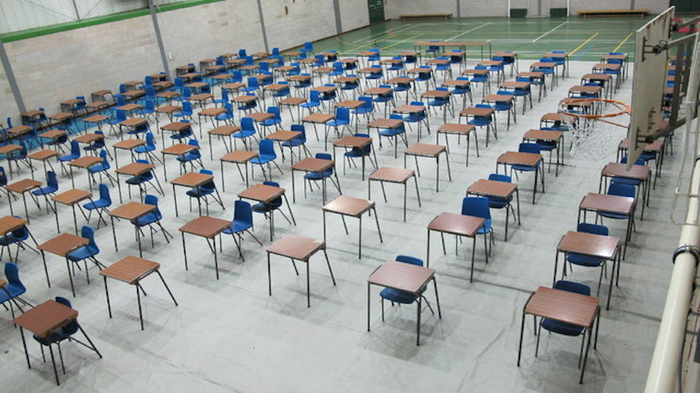

I may well have been able to benefit from art and design classes by working on something I felt sincerely passionate about rather than the prescriptive weekly tasks, or even by writing about artwork and exhibitions instead of creating art myself (which I did have the chance to do for my Arts Award). If a subject is fundamentally about self-expression, each individual will have a specific way of engaging with it which suits them best. However, as many of us will agree, the British education system does not prioritise self-expression; it prioritises assessment. At my secondary school, art and design classes were taught exactly like any academic subject: we had grades, we had assessment objectives, we had fixed classwork and homework. These subjects had all the rigid quantification of maths or science lessons without any of the pretence of utility. As a result, they offered most of us nothing. Some people did happen to be satisfied by the strict approach, but most of us used the lessons as an extra break time and promptly dropped them after Key Stage 3 — and no wonder.

Music and drama were a similar story. I, and many others, pursued music and drama outside school, and sometimes in school-based societies. Curricular lessons simply cannot compare to the experience of focusing intensely on a certain instrument(s), or fully immersing yourself in your role in a production, with like-minded, passionate musicians and actors. While there is often standardised testing involved in these subjects (remember the Grade 5 Theory slog?), they are self-directed in a way that standard classes aimed at students with wildly different interests cannot be. Committed, self-motivated preparation for performances or even for grades can give students the tools to become confident and expressive in whatever art they choose. No national curriculum guidelines are needed for this.

“Without the incentive to rank students, our freedom was almost boundless.”

Underprivileged students often lack the means or encouragement to pursue the arts. This is a problem. But arguing that more money should be pumped into curricular arts lessons, only for them to be ruined by an exam-oriented system which isn’t designed for them, is the wrong way to solve it.

Instead, freeing up some time in the school week for students to take government-funded or subsidised music, art or drama lessons independently of school could give every child the opportunity to become dedicated to an art form: an opportunity which currently tends to be a preserve of students who can afford private lessons. It would also give a new level of autonomy to arts teachers, and allow for more innovative pedagogy.

The Arts Award is a superb model of what arts education can achieve when unfettered by the national curriculum. I did have to produce my own art: I put together a photography project exploring different architectural styles (and wrote an essay to accompany it). I wrote some poems and a play. I also had to submit a final, cohesively-organised portfolio to be judged, which I did by tying all of my work into the general theme of ‘global cultures through art.’

The portfolio had to contain a couple of reviews of shows or exhibitions which linked to my chosen general theme; this allowed me to engage with a wide range of art forms, including those which I appreciated but didn’t enjoy creating. There was no incentive to rank students against each other or quantify our performance, and so our freedom to create projects which genuinely inspired us was almost boundless.

I’m not saying that GCSE and A-level (or equivalent) qualifications in the arts should be scrapped; they do certainly suit some people. But judging by my experience of national arts curricula, I think it's safe to say that most people do not fall in love with the arts through school lessons, especially in Key Stage 3 and earlier. If we acknowledge that the assessment-oriented model used for academic subjects does not work for the arts, there is no reason to cling to it.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026