How the British school system is killing creativity

Looking back on her A-Levels, Miranda Stephenson reflects on how the school system’s focus on examination and functionality harms the learning process

My A-Level results day? I don’t actually remember it very well. I think I awkwardly said goodbye to some teachers before barrelling out of the door. That was all. I was the gingerbread man in a school skirt, and I had long since crumbled.

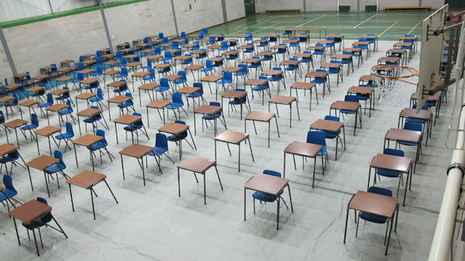

Naturally, like many of my friends, I had been building up to this day since forever. Here was the culmination of my entire school career, and if I could only achieve a string of top grades, I’d have made it — whatever ‘it’ was. I’d be happy. The funny thing is, I had thought the same about my mocks, the same about my GCSEs, and even something similar about my SATs at age 11. For years and years, I had been told that every exam would be my make-or-break point. The school system had nurtured a big, bad, wolfish fear of failure, tied me to a tree in the middle of the forest, and then acted surprised when I was finally gobbled up.

Don’t get me wrong: I received the results that I wanted. The problem was, four capital letters on a sterile white page were never going to cure my numbness. The overwhelming stress that led up to my A-Levels had left me feeling hollow.

Maybe it’s an angry teenage mentality, but I really do blame the government.

It’s not exactly a secret that the British school system is obsessed with assessments. A holistic approach to education was abandoned decades ago. Our government can’t stomach the thought of school children learning philosophy and cooking — especially considering that kids in China spend 15 hours a week on maths alone. Besides, an assessment-centred approach brings tangible results. In 2018, Britain rose through the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) rankings in maths, science, and reading, bursting into the top 20 in all three areas. Education secretary Gavin Williamson was quickly self-congratulatory, applauding ‘more rigorous primary assessments and more pupils… studying the core academic subjects at GCSE.’ Predictably, he failed to mention the report’s less savoury findings: British girls were the 5th most afraid to fail their exams in the world, and more than one in five experienced depression or emotional disorders before their 19th birthday. For me, like many, Britain’s educational strategy proved to be a callous trade-off.

"By the end of my two years at sixth form, it seemed as though my personality had been peeled away."

By the end of my two years at sixth form, it seemed as though my personality had been peeled away. Consciously or unconsciously, I had made the decision that my hobbies had to go; I shrugged them off like second, unnecessary skin. How could I tell myself I was ‘trying my best’ if I read for pleasure when I could have been revising? I kept a little scrap of paper on top of my desk, where I noted down every single minute that I spent studying. The clock breathed down my neck. Eventually, I started skipping meals too. In the government’s desperation to placate fears of global intellectual obscurity, mental health — my mental health — had become disturbingly neglected.

Sometimes, I wonder what path I might have chosen if the system was a little less rigid. I was always interested in drama and art, but I had come to see these as trivial distractions, which were to be put on hold whenever my examined subjects demanded attention. God forbid I’d have ever chosen to study them as bona fide A-Levels. After all, there’s not just a government pressure to pass exams, but also an overbearing pressure to pass the right exams. In just the same way that hobbies are neglected in favour of set, personal-statement-boosting supra-curricular activities, a diverse range of subjects are increasingly devalued in favour of those deemed most ‘facilitating.’ As a humanities student, I had been asked to consider Maths for A-Level; as a STEM student, my sister was told to take extra Physics instead of Art. No matter how many vague platitudes my secondary school spewed, the dominant emphasis was never on creative thinking or independence of choice, but on a subject’s supposed 'utility.'

'Why is it that the creative subjects I most enjoy implicitly carry less worth?"

Ultimately, whoever decided that the arts no longer mattered did their job — with a chainsaw’s grace. From 2016-2019, students studying English for A-Level fell by a fifth, while those who took sciences rose by the same amount. Australia, which advocates for increased educational exchange with the UK, has even announced plans to double the price of university courses in pariah humanities subjects. It seems strange. Today, I still use art techniques I learnt at fifteen, but I have never applied anything from GCSE Physics. In a post-Brexit world, basic language skills would be extremely useful beyond the Anglosphere, but GCSE Japanese is practically unheard of. Maths, meanwhile, even comes in a ‘further’ edition. Whilst Williamson celebrated ‘the core academic subjects’, I can’t help but wonder: why is it that the creative subjects I most enjoy implicitly carry less worth?

When it comes down to it, why we study and what we study have become rigid stepping-stones on the path to government-approved success. A trilingual kid is told that if he can’t label a cell, he’s stupid; a musician’s parents despair when she can’t master the quadratic equation. It’s almost as if we’ve forgotten what it feels like to learn because we love it.

"It’s almost as if we’ve forgotten what it feels like to learn because we love it."

Studying should not be shackled to utility. Education should not be fettered to examination. Learn the capital cities of every country in the world for fun, or choose not to; read voraciously because you want to read, rather than because you’ve been told a particular book is a classic; take up Russian when you’re forty because you’re never too old to try; code video games when you’re 'supposed' to be an ASNAC; complain about historical figures like you know them personally. Maybe then the government will finally see that hopes and dreams cannot be bundled up into exam result envelopes.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026