Straight men don’t want gay friends

Dylan Pugh reflects on being socially excluded by straight men at Cambridge.

Content Note: mention of homophobia

It’s my first week at Cambridge and I am walking to a lecture with the other people from my course at my college. We make the casual, boring small talk of freshers’ week. Except, I have no idea what they’re talking about. I try to ask, but I am met with smirks, half-explanations and at worst I am ignored. Any attempt to change the conversation, about an artist I’ve never listened to, is likewise ignored. I soon learn to smile along with the others, smirk and snort as they do. I end up talking to the only girl of the group. We have nothing in common except she is equally as bored with the conversation as I am.

Now, this event would not have irritated me much, except that it is part of a trend that I have been experiencing my entire life. Being excluded by straight men is not unfamiliar territory for me - by this point it’s to be expected. I recall being called gay in the playground as early as 9; at age 13, a boy I considered a good friend suddenly started mocking my apparent effeminacy; and just this year a friend standing next to me used the word “gay” to describe his broken TV.

"To be accepted around you, I have to dilute my gayness, my voice must become deeper, slower, my “S” sounds less pronounced"

Context aside, this singer formerly unknown to me became the topic of discussion for the entire week, and the week after, and frequently re-appeared throughout the term. Yet the conversation also took different forms: sometimes it was about TV shows I had never watched, football games I had no interest in or humorous videos I had never seen. Once again a group of men had pulled up the conversational drawbridge on me, preventing me from entering their clique; their logic perhaps being that if I wasn’t able to contribute, I would simply go away. And although I do accept the fact that we may have been very different people with very different interests, I also find it hard to believe that we could not have found some common ground, if they had just been bothered.

In my teenage naivety, I let all this wash over me. But as I moved into second year I started noticing this behaviour more and more. On a train one time, I attempt to make conversation with my straight friend opposite me. He looks me up and down, ignores me, and then turns round to talk to my heterosexual friends. Not an uncommon occurrence. Later that year, a straight friend is being teased at pre-drinks about being attracted to a famous sportsman. He is embarrassed by the jokes and eventually becomes angry and sullen - apparently believing that there exists nothing more embarrassing than being attracted to someone of the same gender. I observe in complete silence.

I don’t want to be the boy that cried homophobia, but then why am I constantly being shunned and patronised by straight men? To be accepted around you, I have to dilute my gayness, my voice must become deeper, slower, my “S” sounds less pronounced. I laugh at your unfunny jokes, whereas mine are met with shrugs and calls of ‘I don’t get it’. When I put forward essay ideas they are cast aside immediately whereas you hold each other’s up to heights mine could never reach. Whenever my work is marked higher than yours, you call ‘favouritism’ because my talent could obviously never equal yours. With you I am one of the girls, because even though I am a man, I am still classed as the ‘other’. I am forever a boy but not ‘one of the boys’. I’ve manipulated my voice, my personality, my walk, even my conversation for you my entire life and I receive nothing in return. I’m tired of spending my time attempting to understand your ways but when I ask what you’re talking about your refrain is ‘you won’t get it’ or ‘you don’t want to know’. I do want to know, you just won’t let me. It’s the same reason that I’m the one who gets called ‘fabulous’; this isn’t a compliment, it’s patronising.

"I learnt that a clique that thrives off exclusion is probably one I wouldn’t want to join in the first place"

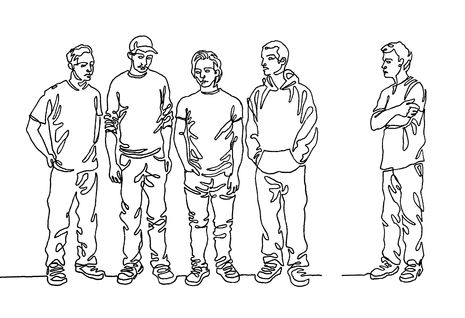

The saddest thing is that I realised recently how this straight male rejection has affected me. After a lifetime of male isolation I’ve ceased trying to be the straight man’s friend. As I currently search for post-university accommodation, I find it too ‘risky’ to live with a seemingly straight man. When asked to join the flat hunt with a group of men I turned them down, attempting to pre-empt the rejection I would doubtlessly receive. One time at a party last year, in order to reach the toilets I had to walk through a throng of lads. I couldn’t do it alone. I feared them, their stares and whispers. One of them started talking to me, I was petrified. My voice deepened, and through the blur of a few drinks I had to become “straight me” again - blushing as my friends watched the entire performance.

The experiences I’m describing aren’t homophobic slurs. It’s the cold veneer that I’m never allowed to see past. It’s the glassy-eyed stare that I’m given when we’re first introduced. It’s the incomprehensible distance he feels between him and me, the distance I have been forced to travel my entire life. It’s the constant questioning after the straight man inevitably rejects my friendship, as I interrogate myself as to why I’m still not good enough for him.

Straight men don’t want gay friends; this conclusion I have been forced to make. Starting with that fresher’s week conversation, during my time at university I have been treated as an equal by the minority of straight men I have encountered. Coming out just before Cambridge, I hoped that here I would be fully accepted; instead I have been subjected to the same exclusion that I’d lived through my entire life. This article is the product of years of rage I have felt playing the straight man’s disposable sidekick. It is the result of hundreds of isolated incidents, just the very best of which grace this text. But in every upset there is something to be learnt. I learnt that none of this rejection was my fault. I learnt to stop chasing validation through straight male friends. And I learnt that a clique that thrives off exclusion is probably one I wouldn’t want to join in the first place.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 Fashion / The art of the formal outfit 18 December 2025

Fashion / The art of the formal outfit 18 December 2025 Lifestyle / Summer lovin’ had me so… lonely?18 December 2025

Lifestyle / Summer lovin’ had me so… lonely?18 December 2025