Finding how I fit into Black spaces

An anonymous student considers what it means to be mixed race

Am I allowed to call myself Black? Being of mixed heritage means I have a European mother and an African father. My light brown skin is immediate evidence of that.

Even so, though my mother may be white, and I may have grown up without my Black father and entirely in a white setting of family and friends, in the eyes of majority-white Great Britain, I am Black — and by extension, ‘other.’ A woman at a Christmas market once asked my mother whether she had “got me from Nigeria.” This was a very confusing message for a child growing up. I didn’t feel Black, because I knew that my upbringing and family traditions were almost entirely German. I felt devoid of any cultural proof that I could claim a Black identity, despite the fact the white world around me was keen to prescribe me one. This made for a perpetual and painful no-man’s land between two communities.

My mother recently asked me when I first became aware of my race. I couldn’t place it, but I knew that my hair was the most problematic factor for me from primary school age. Back then, my skin didn’t bother me too much — I remember informing people proudly that I had “caramel coloured skin”.

Where hair was concerned, however, I resented mine deeply from the age of seven. It would not be tamed into a single plait to fall smoothly past one shoulder like that of my white friends. Instead, every morning at 8:45 there would be yanking and brushing at the mercy of my mother’s hands to disentangle my mane – God forbid I left the house looking too ‘wild.’

People still tell me today that my hair looks ‘wild’ if I wear it as an afro; however well-intentioned, it ultimately serves as a constant reminder that my natural hair is unruly, and needs to be tamed and disguised as much as possible.

It was only when I was 16 and introduced to box braids that I managed to take pride in and embrace the stuff that grew out of my head as mine, and as Black. They made me look immediately more African and feel a stronger connection to my Black heritage.

I was recently turned away from an all-BME play after various auditions for being too light-skinned

I have rarely had to deal with the malicious kind of upfront racism that Black men in particular experience constantly, such as racial profiling by the police. Most of the comments I receive are microaggressions that arise from ignorance: in a German playground, “Why is your skin so dark?”; at high school, as Black American culture reached us over the internet, “Yo, ma nigga!”; questions about my hair were always variations of “Do you brush your hair?,” “Can you wash it?,” or “Can I touch it?”

More recently, at university, a girl approached me in a club asking for drugs. I was baffled; at first I had no idea why she would be asking me, who had never experimented with anything. To her, though, it was clearly quite logical that someone who looked like me would have drugs. When I revealed that I was in fact not a drug dealer, she looked even more confused than me. “What? But you look like you would,” she remarked, as she tottered off.

These comments are never enough to make me feel inferior or uncomfortable in my skin for long. In fact, I’ve often wanted to be darker, so that I could maybe fit more neatly into a Black identity. I was recently turned away from an all-BME play after various auditions for being too light-skinned.

Being rejected because of my skin colour stung — it was like someone had confirmed to me: “no, you’re not really part of this group either.” I am treated everyday as Black by the white world around me, but this episode felt like a door was shut between myself and the solidarity of the Black community.

Though I seem to be processed as Black by white people around me, I will often hear racist tropes being used in conversations I’m part of, which immediately position me as an outsider. On visits to family in Germany and Austria, this has become increasingly apparent as anxieties over immigration have grown. At a family friend’s barbecue in Germany, I was informed that non-European immigrants, especially Muslims, just do not fit into German culture. The German Volk should not be victim to such developments. On other occasions, I have heard white people use the n-word casually around me, knowing that nobody else will react with any discomfort. And then there are the people who assume I’m “doing really well for someone from my background” because surely I must be “disadvantaged”. ‘Sympathy’ of this sort is humiliating and incredibly disrespectful.

Finding compassion but not solidarity for these kinds of experiences at home, I’m pushing myself to seek out more solidarity from a wider field. Over the past year, I have still found myself regrettably anxious to go to BME-only groups and events, worried that I wouldn’t fit in, or would be rejected again as someone who is only half-African, was brought up in a white household, went to a majority-white high school, and is ultimately light skinned.

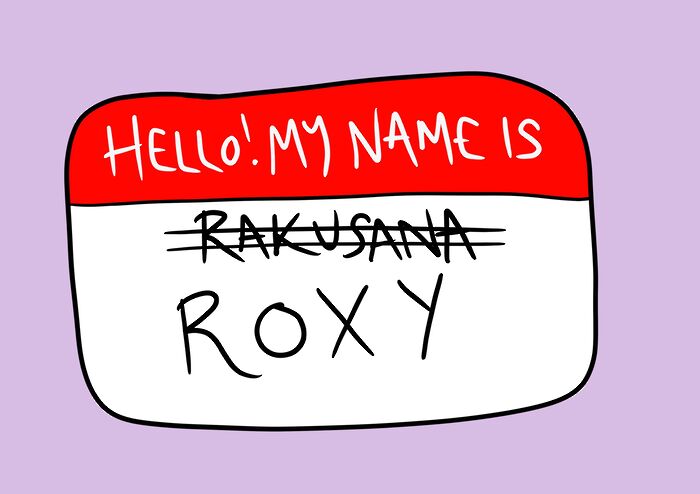

Can I describe myself as Black? I’m still chewing on it. What I know is that my experience definitely isn’t white. Recently getting box braids done, my hairdresser told me that in Jamaica, where slavery made everybody a different shade of brown, I would never be addressed as mixed race, but simply ‘light-skinned’ or a ‘brown skin girl’. This seems like a much healthier way to self-identify that I will embrace, and for the first time give myself my own race.

News / Cambridge bus strikes continue into new year16 January 2026

News / Cambridge bus strikes continue into new year16 January 2026 News / Uni members slam ‘totalitarian’ recommendation to stop vet course 15 January 2026

News / Uni members slam ‘totalitarian’ recommendation to stop vet course 15 January 2026 Science / Why smart students keep failing to quit smoking15 January 2026

Science / Why smart students keep failing to quit smoking15 January 2026 Interviews / The Cambridge Cupid: what’s the secret to a great date?14 January 2026

Interviews / The Cambridge Cupid: what’s the secret to a great date?14 January 2026 Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026

Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026